Direct Action

Women’s liberation is at its heart a struggle for the liberation of all humanity from the most treacherous and insidious forms of oppression and domination.

Women’s Internationalism against Global Patriarchy

- Issue #8

- Author

The struggle against patriarchy — whether organic and spontaneous, or militant and organized — constitutes one of the oldest forms of resistance. As such, it carries some of the most diverse arrays of experience and knowledge within it, embodying the fight against oppression in its most ancient and universal forms.

From the earliest rebellions in history to the first organized women’s strikes, protests and movements, struggling women have always acted in the consciousness that their resistance is linked to wider issues of injustice and oppression in society. Whether in the fight against colonialism, religious dogma, militarism, industrialism, state authority or capitalist modernity, historically women’s movements have mobilized the experience of different aspects of oppression and the need for a fight on multiple fronts.

The State and the Erasure of Women

The division of society into strict hierarchies — particularly through the centralization of ideological, economic and political power — has meant a historic loss for the woman’s place within the community. As solidarity and subsistence-based ways of life were replaced with systems of discipline and control, women were pushed to the margins of society and made to live sub-human lives on the terms of ruling men. But unlike what patriarchal history-writing would have us believe, this subjugation never took place without fearless resistance and rebellion emerging from below.

Colonial violence, in particular, has focused on the establishment or further consolidation of patriarchal control over the communities it wanted to dominate. Establishing a “governable” society means to normalize violence and subjugation within the most intimate interpersonal relationships. In the colonial context, or more generally within oppressed communities and classes, the household constituted the only sphere of control for the subjected male, who seemed to be able to assert his dignity and authority only in his family — a miniature version of the state or colony.

Over the centuries, an understanding of familial love and affection developed that split from its roots in communal solidarity and mutuality, further institutionalizing the idea that violence and domination is simply part of human nature. As authors like Silvia Federici and Maria Mies have argued, capitalist imperialism — with its inherently patriarchal core — has led to the destruction of entire universes of women’s lifeways, solidarities, economies and contributions to history, art and public life, whether in the European witch hunts, through colonial ventures abroad, or through the destruction of nature everywhere.

In modern times, many feminist activists and researchers have critiqued the relationship between oppressive gender norms and the rise of nationalism. Relying fundamentally on patriarchal notions of production, governance, kinship and conceptions of life and death, nationalism resorts to the domestication of women for its own purposes. This pattern is recurring in today’s global swing to the right, with fascists and far-right nationalists often claiming to act in the interests of women. Protecting women from the unknown, after all, remains one of the oldest conservative tropes to justify psychological, cultural and physical warfare against women. As a result, women’s bodies and behaviors are being instrumentalized for the interests of an increasingly reactionary capitalist world system.

In modern times, many feminist activists and researchers have critiqued the relationship between oppressive gender norms and the rise of nationalism. Relying fundamentally on patriarchal notions of production, governance, kinship and conceptions of life and death, nationalism resorts to the domestication of women for its own purposes. This pattern is recurring in today’s global swing to the right, with fascists and far-right nationalists often claiming to act in the interests of women. Protecting women from the unknown, after all, remains one of the oldest conservative tropes to justify psychological, cultural and physical warfare against women. As a result, women’s bodies and behaviors are being instrumentalized for the interests of an increasingly reactionary capitalist world system.

Colonialism yesterday and capitalist militarism today immediately target the spheres of communal economy and the autonomy of women within them. As a result, epidemic waves of violence against women destroy whatever was left of life before capitalist social relations and modes of production took hold. No surprise then, that women, feeling capitalist domination and violence most intensively and from all sides, are often at the forefront in the Global South to fight against the capitalist destruction of their lands, waters and forests.

Imperialist Feminism and Patriarchal Socialism

Let us identify two further issues that radical women’s struggles need to engage with today.

Perhaps the older of the two is the sidelining of women’s liberation by progressive, socialist, anti-colonialist or other leftist groups and movements. Historically, although women have participated in liberation movements in various capacities, their demands were often pushed aside in favor of what was identified by (usually male) leaders as the priority objective. This, however, is not an occurrence inherent to struggles for socialism or other alternatives to capitalism. It is, in fact, rather a demonstration of how deep the fight against oppression and exploitation needs to reach if real change is to be brought about.

The authoritarian traits of past historic experiences, based on their high-modernist and statist obsessions bordering on social engineering, are very much in line with patriarchal conceptualizations of life. As many feminist historians have pointed out, class has always meant different things to women and to men, particularly as women’s bodies and unpaid labor were appropriated and commodified by dominant systems in ways that naturalized their subjugated status profoundly.

As an outcome of millennia-old feminicidal systems, many of which do not feature in history classes even today, combined with the everyday reproduction of patriarchal domination in hegemonic culture, intimate relationships or in the seemingly loving sphere of the family, deep psychological traumas and internalized behaviors produce a need to radically break with societal and cultural expectations of passive femininity and womanhood through consciousness-raising, political action and autonomous organizing.

As the experience in our own movement — the women’s struggle in the Kurdish freedom movement — has shown, without a total divorce from patriarchy, without a war on our internalized self-enslavement, we cannot play our historic role in the general struggle for liberation. Neither can we find shelter in autonomous women’s spheres without running the danger of separating ourselves from the real concerns and problems of the society — and with that, the world — that we seek to revolutionize. In this sense, our autonomous women’s struggle has become our people’s guarantee to democratize and liberate our society and the world beyond.

The flipside of this negative experience of women’s movements within broader struggles for liberation is related to the second and more recent issue that women’s struggles face today: the de-radicalization of feminism through liberal ideologies and systems of capitalist modernity. Increasingly so, progressive movements and struggles that have the potential to fight power are confronted with what Arundhati Roy refers to as the “NGO-ization of resistance.” One of the primary tools to enclose and tame women’s rebellion and rage is the delegation of social struggles to the realm of civil society organizations and elite institutions that are often necessarily detached from the people on the ground.

It is no coincidence that every country that has been invaded and occupied by Western states claiming to import “freedom and democracy” is now home to an abundance of NGOs for women’s rights. The fact that violence against women is on the rise in the same aggressor countries should raise questions about the function and purpose that such organizations play in the justification of empire. Issues that require a radical restructuring of an oppressive international system are now reduced to marginal phenomena that can be resolved through corporate diversity policy and individual behavior, thus normalizing women’s acceptance of cosmetic changes at the expense of radical transformation.

It is no coincidence that every country that has been invaded and occupied by Western states claiming to import “freedom and democracy” is now home to an abundance of NGOs for women’s rights. The fact that violence against women is on the rise in the same aggressor countries should raise questions about the function and purpose that such organizations play in the justification of empire. Issues that require a radical restructuring of an oppressive international system are now reduced to marginal phenomena that can be resolved through corporate diversity policy and individual behavior, thus normalizing women’s acceptance of cosmetic changes at the expense of radical transformation.

Today, women are expected to cheerlead self-congratulatory manifestations of the most overt forms of imperialism and neoliberalism for their “gender inclusivity” or “female friendliness.” This grotesque appropriation of women’s struggles and gender equality was demonstrated in a recent joint article in The Guardian, co-authored by Hollywood star and UN ambassador Angelina Jolie and NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg, in which the two made public their collaboration to ensure that NATO fulfils “the responsibility and opportunity to be a leading protector of women’s rights.”

The imperialist mentality underlying the logic that NATO, one of the main culprits of global violence, genocide, unreported rape, feminicide and ecological catastrophe, will lead the feminist struggle by training its staff to be more “sensitive” to women’s rights is a summary of the tragedy of liberal feminism today. Diversifying oppressive institutions by supplementing their ranks with people of different ages, races, genders, sexual orientations and beliefs is an attempt to render invisible their tyrannical pillars and is one of the most devastating ideological attacks on alternative imaginaries for a just life in freedom.

Both right-wing conservatives and misogynist, authoritarian leftists, particularly in the West, are quick to blame “identity politics” and their supposed fragility for today’s social problems. The term “identity politics”, however, was coined in the 1970s by the Combahee River Collective, a radical Black lesbian feminist group that emphasized the importance of autonomous political action, self-realization, consciousness-raising for the ability to liberate oneself and society on the terms of the oppressed themselves. This was not a call for a self-centered preoccupation with identity detached from wider issues of class and society, but rather a formulation of experience-based action plans to fight multiple layers of oppression.

The problem today is not identity-based politics, but liberalism’s co-optation thereof to remove its radical intersectional and anti-capitalist roots. As a result, mostly white female heads of state, female CEOs and other female representatives of a bourgeois order based on sexism and racism are crowned as the icons of contemporary feminism by the liberal media — not the militancy of women in the streets who risk their lives in the struggle against police states, militarism and capitalism.

Focusing on identity as a value in itself, as liberal ideology would like to have us, runs the danger of falling into the abyss of liberal individualism, in which we may create sanctuaries of safe space, but ultimately become directly or indirectly complicit in the perpetuation of a global system of ecocide, racism, patriarchal violence and imperialist militarism.

Internationalism Means Direct Action

One of the primary tragedies of alternative quests is therefore the delegation of one’s individual or collective will to instances outside of the community-in-struggle: men, NGOs, the state, the nation, and so on. The crisis of representative liberal democracy is very much related to its inability to deliver its promise, namely to represent all sections of society. As oppressed groups, particularly women, have historically experienced, one’s liberation cannot be surrendered to the same systems that reproduce unbearable violence and subjugation. In the face of these false binaries that women’s struggles are often confronted with, the urgency of internationalism emergences even more insistently.

At the heart of internationalism has historically been the realization that beyond any existing order, people must be conscious of each other’s suffering and see the oppression of one as the misery of all. Internationalism is a revolutionary extension of one’s self-awareness to the realm of humanity as a whole, based on the ability to see the connections of different expressions of oppression. In this sense, internationalism must necessarily reject any form of delegation to status quo institutions and must resort to concrete, direct action.

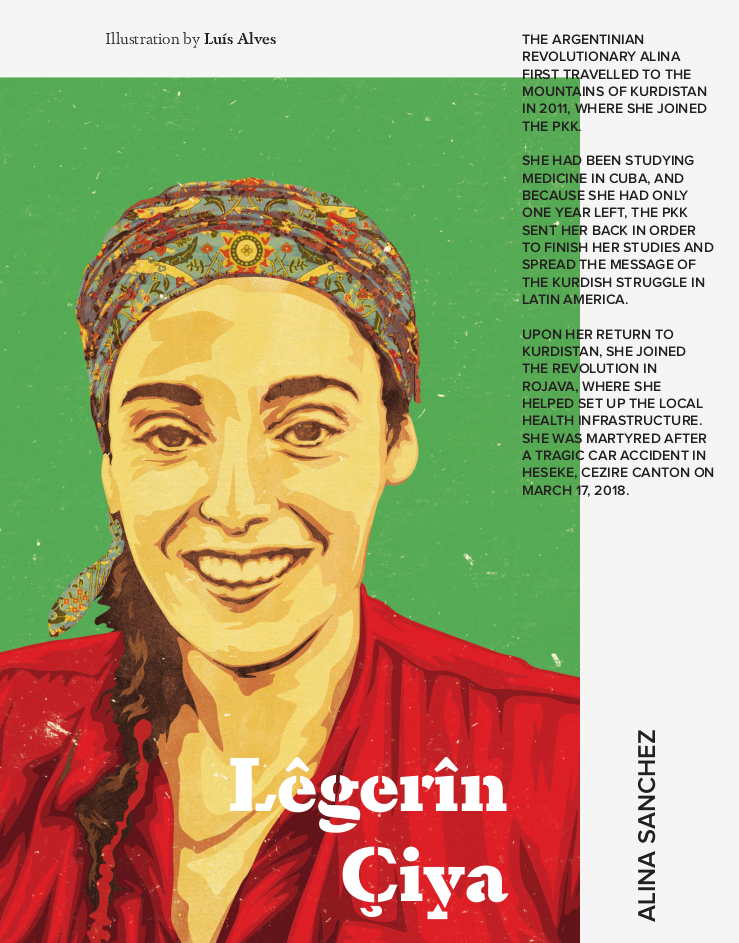

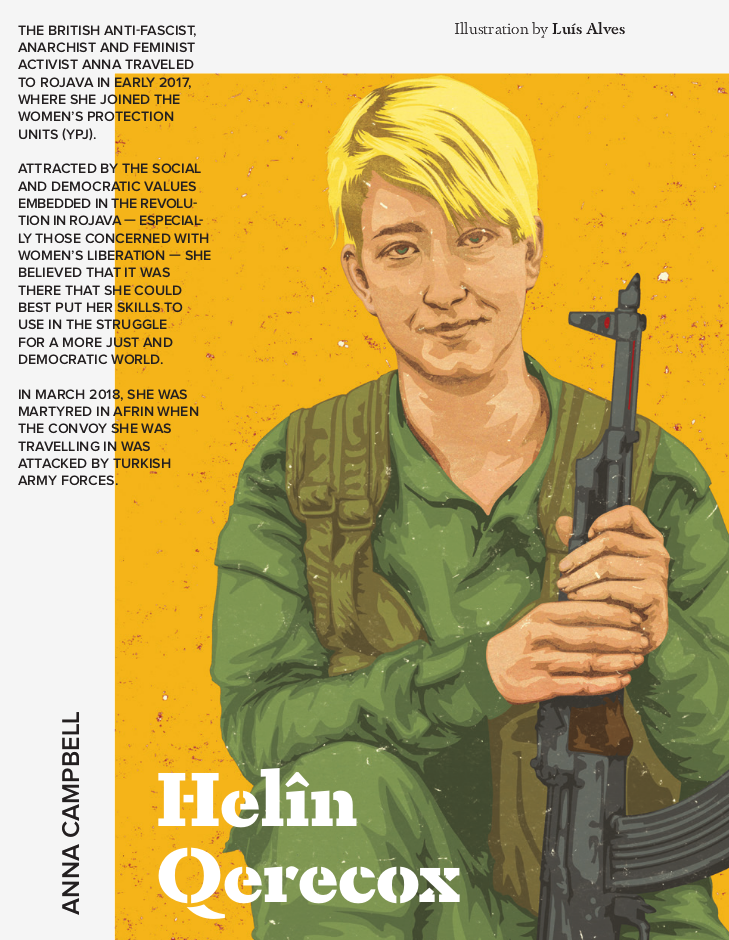

More than one hundred years ago, the month of March was chosen by socialist working women to be the international day of women and their militant struggles. A century on, March has become the month to commemorate and honor women internationalists in the revolution of Rojava. This past March, two remarkable militant women, Anna Campbell (Hêlîn Qerecox), a revolutionary anti-fascist from England, and Alina Sanchez (Lêgêrîn Ciya), a socialist internationalist and medical doctor from Argentina, lost their lives in Rojava during their quest for a life free from patriarchal fascism and its mercenaries under capitalist modernity.

Three years earlier, in March 2015, one of the first internationalist martyrs of the Rojava Revolution, the Black German communist Ivana Hoffmann, lost her life in the war on the feminicidal rapist fascists of ISIS. Together with thousands of Kurdish, Arab, Turkmen, Syriac Christian, Armenian and other comrades, these three women, in the spirit of women’s internationalism, insisted on being on the frontlines against the destruction of women’s lifeworlds by patriarchal systems. At the time of writing these words, more than three months on, Anna’s body still lies hidden under the rubble in the midst of the colonial, patriarchal occupation of the Turkish state in Afrin, Rojava.

At the heart of these women’s defense of humanity was a commitment to beautify life through permanent struggle against fascistic systems and mentalities. In the spirit of the revolution that they joined, they did not compromise their womanhood for the sake of a liberation that marginalizes the struggle against patriarchy.

Towards the end of last year, Kurdish, Arab, Syriac Christian and Turkmen women, together with internationalist comrades, announced the liberation of Raqqa and dedicated this historic moment to the freedom of all women in the world. Among them were Ezidi women, who organized themselves autonomously to take revenge on the ISIS rapists that three years previously committed genocide against their community and enslaved thousands of women.

Revolutionary women’s struggles — as opposed to contemporary liberal appropriations of feminist language — have always embodied the spirit of internationalism in their fights by taking the lead against fascism and nationalism. To stay true to the promise of solidarity, internationalist politics in the vein of women’s struggles, must understand that oppression can operate through a variety of modes, so that both the violence as well as the resistance against it do not have to resemble each other everywhere.

Today’s internationalism needs to reclaim direct action for systemic change without reliance on external powers — party, government or state — and must be radically democratic, anti-racist and anti-patriarchal.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/womens-internationalism-global-patriarchy/

Next Magazine article

Internationalists in the Revolution

- Internationalist Commune of Rojava

- September 26, 2018

Africa’s Place in the Radical Imagination

- Zoé Samudzi

- September 26, 2018