Photo: Kurdish Struggle

Rojava dispatch: for whom doth the bell toll in Syria?

- December 4, 2015

Imperialism & Insurgency

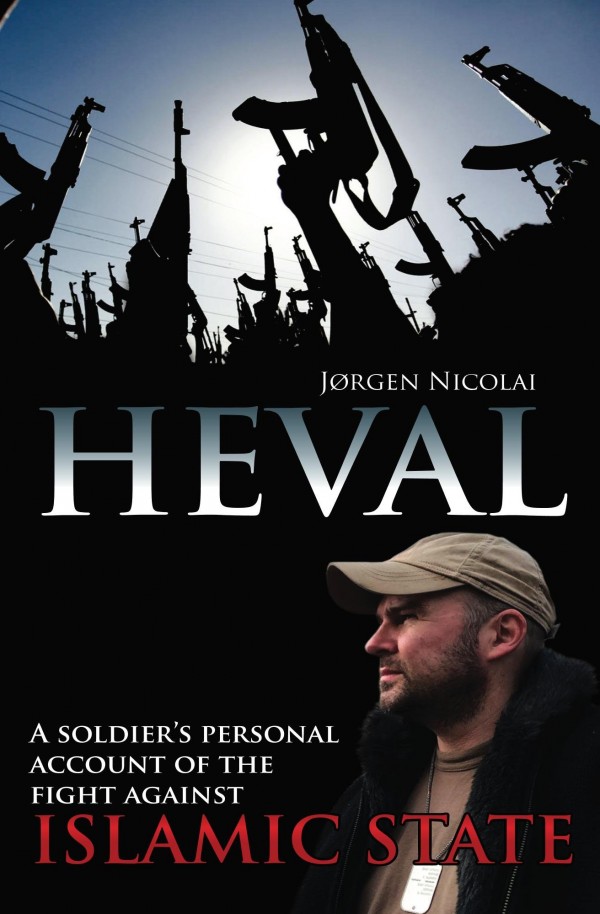

“Chilling and authentic”: a review of Heval, the first in-depth eye-witness account of the war against ISIS by a Western volunteer who joined the YPG.

- Author

In late 2014, Jørgen Nicolai, a mechanical engineer from Denmark, bid goodbye to his wife and young daughter and boarded a plane bound for the city of Erbil in northern Iraq. From there he was smuggled into eastern Syria, where he spent several months with the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, or YPG, fighting against some of the most fanatical and fearsome fighters on the planet: the men who fly the black flag of Islamic State.

Having barely made it out alive, Nicolai has now written a book, Heval: A Soldier’s Personal Account of the Fight Against Islamic State, in which he chronicles his experiences.

This book is the first in-depth, eye-witness account of the war against Islamic State that has been published in English, and the perspective it provides on the conflict is invaluable. Although Nicolai’s story itself makes for an exhilarating read, the book’s real value lies in the insights it offers into the Kurdish struggle, the gruesome tactics employed by Islamic State, and the process by which ordinary men and women can wind up risking their lives fighting in “other people’s wars”.

For Nicolai, the conflict in Syria was always likely to become personal; having lived and worked in the country before the war, he had built up a substantial network of Syrian friends and acquaintances. He followed the uprising against Assad with a keen eye, and watched with dismay as his adopted city of Aleppo was gradually reduced to rubble.

When a close Syrian friend of his was abducted from his home by Islamic State militants, and this man’s wife and children forced to flee to Iraq in search of refuge, Nicolai felt obliged to do something.

Joining the militia

After speaking to his friend’s relatives and making a few contacts via Facebook, Nicolai flew to the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, Erbil, with $1,000 in cash and a suitcase full of children’s winter clothes. His first mission was to deliver these to his friend’s family, whom he had been told were now living in a United Nations refugee camp not too far from Erbil.

Though food, water and electricity were available at this camp, it was a miserable place to live. Muddy tracks ran between the tents. Broken families were the norm; old men staggered about aimlessly while orphans in rags rummaged through piles of moist garbage.

Nicolai found his friend’s wife all but a shrunken shadow of her former self. “She looked old and tired,” he writes. “She had deep, dark rings under her eyes, as if she had been crying for a long time.” Which, of course, she had been; her husband was almost certainly dead, and she and her children were homeless. Her life, like that of so many other Syrians, was in ruins.

After spending a couple of weeks visiting the family and doing what more he could to help them, Nicolai approached the Kurdish authorities with a request to join their militia, the peshmerga, to whom he could offer his services as a technician. But although his initial meetings with the Kurdish security forces seemed promising, his offer was ultimately rebuffed; western governments such as Denmark’s were none too keen on their own citizens participating in the conflict, and had apparently asked the Kurds to prevent foreign volunteers like Nicolai from signing up with them.

The situation in Syria was different, however. Nicolai knew that the YPG were accepting foreigners, as he had already made online contact with them back in Denmark. After being rejected by the peshmerga, he tapped his connections in the YPG and they arranged for him to be smuggled across the border.

The situation in Syria was different, however. Nicolai knew that the YPG were accepting foreigners, as he had already made online contact with them back in Denmark. After being rejected by the peshmerga, he tapped his connections in the YPG and they arranged for him to be smuggled across the border.

Nicolai describes how he was then transported to a safe house in Sulemaniyah, in southern Iraqi Kurdistan, and from there to an isolated guerrilla camp nestled among the limestone crags of the Zagros mountains in the north. He had to wait here for some time; under pressure from the Turkish government, the Iraqi Kurds had officially closed the border to Syria and it was necessary to wait for an opportune moment to cross it clandestinely.

Up at the camp, in the cold and wet, Nicolai befriended a few other foreigners, ate naan bread with goat’s cheese and marmalade, practiced speaking Kurdish, and drank endless cups of hot tea. At night he could listen to the howling wolves that roamed the mountains. But although he relished this simple lifestyle, like the other foreigners he was becoming impatient; they had not come all this way for a holiday.

Finally the order came to pack their bags. The foreigners gathered their gear and began the long and difficult hike back down into the valley. There they found a pickup truck waiting to take them the rest of the way to the border.

Although the ride that followed was very welcome, it was not a pleasant experience. “We sat like sardines in the back of the truck,” Nicolai recalls. “As we had to drive on small, winding mountain roads, it was not long before we all had aches and pains, and sore tailbones.”

Shipped off to the front

Once he had arrived in Syria, Nicolai encountered many other foreigners who, like himself, had come to join the fight against Islamic State. But although they shared this much in common, their backgrounds differed widely; there were “Christians, Muslims, Yazidis, Jews, Hindus, Africans, Chinese, Europeans, Persians, Arabs, Turks and many others in our ranks.”

Some volunteers, such as the African teenager Nicolai saw manning a heavy machine gun mounted on a pickup truck, or the young Iranian who perished almost as soon as he picked up a weapon, had little or no professional military training.

Others, however, had substantial combat experience: among his comrades Nicolai counted hardened ex-PKK guerrillas, former French Foreign Legionnaires, and decorated British and US special forces veterans who had seen action in conflict zones such as Northern Ireland and Iraq.

Regardless of their background, new recruits were required to undergo a training program to familiarize them with elementary Kurdish, basic battle skills and handling of the Russian-designed equipment they would soon be using.

Nicolai, who already had some military training under his belt, spent only ten days at the YPG academy. After this, he was shipped off in a minivan to the front near Serekaniye — a battle-scarred Syrian-Turkish border town where “people on the Turkish side [of the heavily fortified border] could stand on their balconies and drink tea while the war was being played out in front of them.”

Nicolai, who already had some military training under his belt, spent only ten days at the YPG academy. After this, he was shipped off in a minivan to the front near Serekaniye — a battle-scarred Syrian-Turkish border town where “people on the Turkish side [of the heavily fortified border] could stand on their balconies and drink tea while the war was being played out in front of them.”

Assad’s forces, the Free Syrian Army, the Kurdish YPG and the jihadists had all laid claim to this area, which was now carved up “like Berlin during the Cold War.” The YPG’s front line against Islamic State was relatively static here; both sides had dug in and were more or less content to trade the occasional bullet or grenade rather than risk incurring substantial casualties during a full-scale assault on the other’s positions.

There were regular supply convoys moving through the area, however, and these were more vulnerable to attack than were Islamic State’s fortifications. Nicolai and his team recognized an opportunity to go on the offensive, and began reconnoitering for an ambush on the convoys. The Kurdish base commander, although he needed some convincing, eventually gave his approval to the plan they came up with and even agreed to help assist in its execution.

The attack caught the jihadists completely by surprise; their response was slow and clumsy, and Nicolai and his team escaped the firefight entirely unscathed. Nevertheless, he writes, “after we had returned to camp I could feel both my legs and hands shaking.” They celebrated the small victory that evening at the base with a rare feast of meat and a night of Kurdish dancing around the fire.

He had survived his first encounter with Islamic State.

The traumas of war

Further engagements with the enemy were to prove few and far between, however, and the days that followed were dreary and uneventful. Nicolai eventually became dissatisfied with the lack of action at Serekaniye and requested reassignment to the area around Tel Hamis, a small university town near the Iraqi border, where the front line was more fluid.

Here, he would come face to face with some of the nastier characteristics of this conflict, such as suicide bombers, IEDs, deliberate mutilation of the dead and the use of civilian human shields.

Splashed brains, severed limbs and shattered bodies became ordinary sights for him. On one occasion, cleaning up after a victorious skirmish, Nicolai was required to straddle the body of a jihadist he had just shot dead so as to keep it from sliding off the hood of his Humvee; there was no room for this particular body on the back of the vehicle, as it was loaded up with other corpses.

“I didn’t want to look at those we’d killed,” he writes, “and certainly not touch them … but we had to bury the bodies. If we let them lie in the sun, they would spread disease.”

During another battle, Nicolai came under intense machine gun fire and was forced to take cover next to two dead Kurdish comrades. One of the men was unrecognizable; part of his head had been blown off by the heavy caliber bullets.

During another battle, Nicolai came under intense machine gun fire and was forced to take cover next to two dead Kurdish comrades. One of the men was unrecognizable; part of his head had been blown off by the heavy caliber bullets.

The other dead comrade was someone Nicolai knew; a gentle teenager who had been completely devastated by the loss of his loved ones in the war. Nicolai had been worried about him; “[now] I couldn’t take my eyes off him,” he recalls. “He lay open-mouthed, staring blankly skyward. … I really wanted to cry, but I had to turn my grief into anger; otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to focus on fighting and surviving.”

Nicolai had to grapple with the traumas of war without any of the support normally offered to professional soldiers in the West. Unsurprisingly, the fighting weighed heavily on him.

“I gradually began to feel tired,” he writes. “My body was covered in wounds and bruises. On my hands I had big burn blisters from [my machine gun’s] hot barrel. I could feel that I was more tense and that my patience was running thin. … War, violence and the hard life at the front were beginning to wear me down both physically and mentally.”

He had not seen his family for five months, and he knew that “there were limits to what [his] wife and child could stand.”

Eventually he decided it was time to go home, and went out the same way he came in. After recuperating with his family back in Denmark, he put pen to paper and soon had a finished manuscript in his hands.

A “one hundred percent donation”

The book he then published is clearly focused on his own experiences, but it is not simply the tale of one man’s life at the front. It is also an implicit declaration of solidarity with the Kurdish people and their struggle for freedom. This being so, at no point is the reader exposed to overt political evangelizing; one reads nothing of Abdullah Öcalan or his idea of ‘democratic confederalism’, for example, despite Nicolai’s obvious familiarity with the YPG’s history and ideology.

Nicolai’s own views on the Kurdish socialist experiment and the broader issues surrounding the conflict are in fact rarely made explicit, and when they are expressed they are usually couched in measured terms.

Nevertheless, his repeated comments regarding the limited quality and quantity of the YPG’s weaponry, for example, or the way he describes his Kurdish comrades’ jubilation at the sight of coalition warplanes, seem to be not only simple statements of fact but also gentle reminders that the Kurds are in dire straits and require more support.

Similarly, his genuflections to the generosity and courage of the Kurdish spirit tend to leave the reader asking why this apparently secular, egalitarian and democratic community has in fact been given so little help by the West. With his usual subtlety, Nicolai suggests that this particular question might best be answered by looking more closely at Turkey’s role in the Syrian conflict.

But the proof of the book’s purpose seems reflected in Nicolai’s use of an independent platform to publish it and in his plan for the proceeds from its sales. Nicolai told this reviewer that he chose to publish independently for two reasons: the first being simply that it was easy to do so; the second, that traditional publishing companies take a very large cut from a book sale’s profits.

But the proof of the book’s purpose seems reflected in Nicolai’s use of an independent platform to publish it and in his plan for the proceeds from its sales. Nicolai told this reviewer that he chose to publish independently for two reasons: the first being simply that it was easy to do so; the second, that traditional publishing companies take a very large cut from a book sale’s profits.

This, he says, would have left almost nothing to give to the humanitarian organizations, such as UNICEF and the Kurdish Red Crescent, to which he has pledged to donate all proceeds from the book. “It’s one hundred percent donation,” he insists. “I don’t want to be that guy who profited from the war.”

In any case, Nicolai’s use of an independent publishing platform is not a marker of the book’s quality. Heval is not of the same literary caliber as For Whom the Bell Tolls, it is true, but Nicolai does not presume to be Hemingway. He has his own personal — and refreshingly unpretentious — style of telling a story. He captures atmosphere and personality well, and molds his narrative with considerable skill.

Because the text has not been scrutinized by the eye of a professional editor, however, minor grammatical errors and some strange turns of phrase remain. Oddly enough, this fact only seems to add charm to the book. Nicolai is a Dane who speaks English as his second language, and one clearly detects this northern European accent in the structure of his thoughts and expression. One hears his authentic voice, as it were, as if in direct conversation with him.

A work of fiction, of sorts

Another important point to note is the fact that Heval is listed as a work of fiction, despite the book’s inclusion of many documentary photos and the fact that Danish journalists have verified the central tenets of the story. Nicolai says that he chose to do this not because he has grossly distorted the truth, but simply because he wants to be completely open with his readers.

“Ninety-eight or ninety-nine percent of the book [accurately represents reality],” he says. “And I could have written it as a ‘true story.’ But as Alfred Hitchcock said: drama is life without all the boring stuff. I took some liberties, which I have as an author, but because there are a few small things that are, you could say, made up, I just didn’t want to say that [the book was non-fiction].”

Given this, some caution is warranted when reading Heval as a factual account of the war. Nevertheless, considered in the context of the Danish media’s corroboration of Nicolai’s story, and read next to the brief accounts of other foreign fighters, Heval provides valuable insight into the local textures of a crisis that is now fully global in its consequences.

Reading this book, one smells the acrid decay of civility in Syria and tastes the bitterness of ethnic conflict. Though the freshness of the Kurds’ growing hope, watered though it is by their tears and blood, may seem to bring some small solace from all this, it must be tempered by an awareness of the mistreatment to which the Kurds’ Arab neighbors have increasingly been subject.

Heval provides a vivid portrait of the pain and rage and fear moving so many people in the world today, not only inside of themselves but across international borders. Nicolai’s response to the death of his friend Anas at the hands of Islamic State is of course what stands out here, but one thinks too of the Sunni Arab tribesmen whose grievances have been left to fester and coalesce into that aggressive cancer of a caliphate.

One’s mind turns also to the many Syrian refugees like Nicolai’s friend’s wife and children; to the drowned toddler washed ashore in Turkey, for example, whose family fled the fiery onslaught of Islamic State only to find the cold embrace of death at sea. One thinks too of those who exploited the refugee crisis to murder Parisians in cold blood.

Ultimately, one is forced to reflect on the question of what a single human life should mean to others, and on how fragile humanity can be. Rather chilling, in the context of all this, is it to be reminded of the words of the English cleric John Donne, which inspired the title of Hemingway’s famous account of the Spanish Civil War and which perhaps ring more true today than ever:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were. Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Jørgen Nicolai’s book

Heval: A Soldier’s Personal Account of the Fight Against Islamic State

can be ordered here.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/heval-foreign-fighter-ypg-rojava-book/

Further reading

Why big NGOs won’t lead the fight on climate change

- Belinda Rodriguez, Ben Case

- December 6, 2015

This is not a refugee crisis

- Paul Walsh

- December 2, 2015