Photo: Andrés Díaz

Black flags and debt resistance in America’s oldest colony

- August 2, 2016

Capitalism & Crisis

In the face of a neolcolonial debt regime imposed by the United States, Puerto Rico’s streets are alive with the spirit of resistance.

- Author

Sunday midnight in Santurce, the old downtown working-class neighborhood of Puerto Rico’s capital San Juan which, like seemingly all such neighborhoods around the world, struggles with the uneven brutalities and gifts of gentrification. Old men sit on decaying swivel chairs outside small bars pumping local music, faded newspapers line the insides windows of shops long-shuttered by the island’s ongoing economic crisis.

Yet here and there new businesses and experimental social spaces are also flourishing, thanks to a resurgent spirit of DIY economic development and a stubborn refusal to concede to austerity. Tonight, two small groups of art school graduates – now working a variety of jobs, many in the tourism industry – are painting black and white murals on the walls.

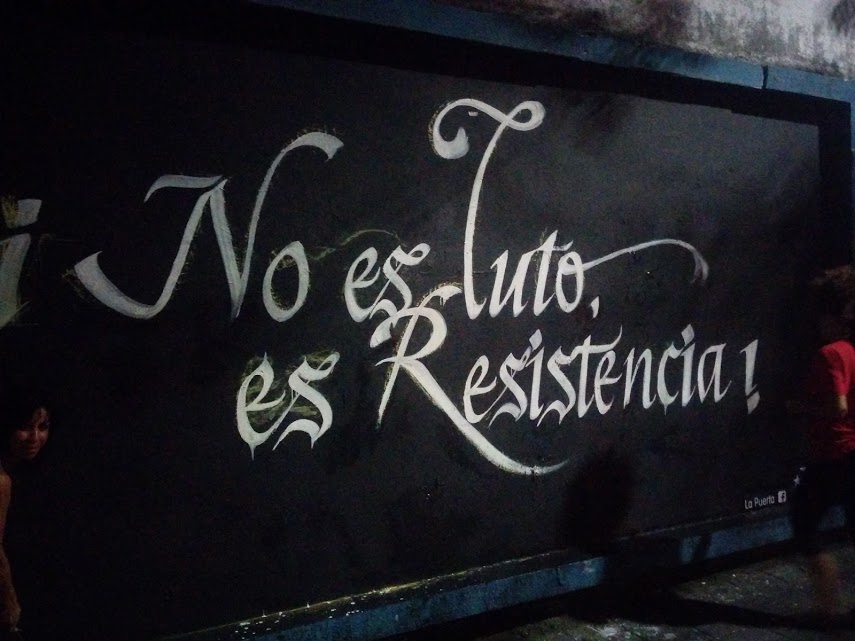

“It’s not mourning, it’s resistance!” one mural reads, referring to its own austere palette and calligraphic lettering. The aesthetic has become a calling card for this informal collective, almost all young women, and stands out starkly in a neighborhood known around the world as home to vibrant, colorful works by international street artists.

Another of their works appears on the same wall: a black-and-white rendering of the flag that represents Puerto Rico’s quest for sovereignty, which first flew over the stockades of the short-lived revolution against Spanish colonialism in the city of Lares in 1866. Here the flag’s horizontal axis has been replaced by that unmistakable symbol of the country’s struggle for independence, the machete, and within it are depicted famous figures from Puerto Rico’s long history of anti-colonial resistance alongside contemporary local activists, all calling out libre!, or freedom.

Most Americans know very little about the island nation and its colonial relation to the United States, despite the fact that it has been so much in the news lately with ominous stories of it’s near-default on a debt of around $70 billion.

With a population of about 3.5 million and a roughly equivalent diaspora living in a range of American cities, Puerto Rico has technically been a territory of the US since 1898. While Puerto Ricans are citizens they do not have an electoral college so cannot vote for President, nor do they have any voting representation in Congress or the Senate. While the island has its own Governor, House of Representatives and Senate that preside over local affairs, a recent bombshell court-case has affirmed that, for all intents and purposes, they sit at the pleasure of the US Congress. In fact, the whole of Puerto Rico was shocked when, during this Supreme Court case last year, the Solicitor General (the White House’s chief legal representative) intervened to insist that, unlike the fifty States of the Union, Puerto Rico had no sovereignty whatsoever.

The sense of betrayal is palpable. Hence the resonance of another mural, a few short blocks away, also in iconic black and white: a spoof on the ubiquitous local Old Colony soda can which features a stylized European toff with tricorn and ribbons. In this version, the aristocrat has been replaced by a skeptical if weary looking panda holding a machete. The scroll beneath features the words “Oldest Colony.”

The oldest colony

It’s common to hear activists talk about Puerto Rico as having been colonized for over 500 years, first by the Spanish, then by the United States. Columbus claimed the island in 1493. He and his followers enslaved and massacred the indigenous Taino people, leading to their eventual extirpation.

Slavery, only abolished in 1873, filled the void, but so too did an increasingly impoverished settler peasantry. By the time of the American invasion in 1898, Puerto Ricans had developed a proud and unique working-class culture that draws on European, African and Indigenous roots and resonates with a spirit of egalitarianism and mutual aid. Hence the importance of street art that prizes the combination of aesthetic joy and political acuity.

The history of colonialism is key to understanding today’s debt crisis. Focusing much more on the nearby and lucrative colony of Cuba, Spain dramatically underdeveloped and largely ignored Puerto Rico, which had the felicitous effect of allowing the islanders to develop their own forms of subsistence agriculture in the lands left fallow by the coffee, sugarcane tobacco and other plantation industries.

Small local landholders and farmers were initially optimistic when the Americans claimed the island at the close of the Spanish-American War in 1898 promising to liberate the population from Old World colonialism, even incorporate it into its democratic union of free states.

But these hopes were quickly dashed when it became clear the rising superpower had no intention of giving up such a strategically located possession or allowing a population of racialized Spanish-speaking islanders to become full citizens (that would only happen in 1917, when the US was desperate for conscripts to WWI).

Indeed, the budding local economy was devastated when, in 1913, Congress by fiat replaced the local Peso with the Dollar as legal tender at an artificially extortionate 7/10 discount, essentially wiping out about 40% of the nation’s wealth in a heartbeat. Small farmers and local businesses were compelled to go heavily into debt and, when the dust settled, major landholders, foreign and domestic, held most of the land.

The population began trickling to the coasts in search of waged work to buy imported food. Since then, Puerto Rico’s major export has been its people and its major imports have been practically everything, since the island has not been permitted to produce much of durable value. The largest sectors of the economy are still today dominated by middlemen who administer (and defend) the relationship of economic dependency.

Neoliberal Paradise

This goes a long way to explaining how this tiny island can, today, be in such deep financial trouble. While local political organizing, including armed resistance, led to greater autonomy and decision-making power for the Puerto Rican government over the 20th century, the US has always viewed its overseas territory as a resource to be exploited. Economic development here has, on the whole, been geared towards making the place a shangri-la for American capitalist investment with absurdly low taxes and a largely impoverished (though increasingly well-educated) workforce.

Operation Bootstrap, the country’s famous New-Deal era economic development plan boiled down to enticements for American corporations to set up shop, bringing much needed wealth jobs and infrastructure, but essentially increasing the nation’s economic dependency on American imports. It is, for instance, estimated that, should those imports cease, the island would only be able to feed itself for two weeks.

As Keynesian models gave way to neoliberal schemes in the Reagan era, the island was exhorted to throw its doors open even wider, leading to the growth of a pharmaceutical branch-plant industry as well as massive, debt-fueled investments in real estate and infrastructure, aimed largely at improving Puerto Rico’s competitiveness with other low-cost jurisdictions like Mexico or China as well as neighboring Caribbean islands, in an age of globalization.

One outcome of this situation is particularly revealing of the broader problem, historically and in the present day: at one point the island nation produced almost all the Tylenol and Viagra on the American market thanks to absurdly low taxes and generous incentives to major pharmaceutical corporations. All the raw materials were imported and the finished product was exported in bulk to the mainland to be packaged at corporate headquarters, then sent back to Puerto Rico to meet local demand (needless to say, all the profits also flowed, nearly tax free, to those corporations).

Due to an obscure colonial law, all imports and exports to Puerto Rico must be made on American-owned and -build ships with American crews, something that is not only extremely rare but extremely expensive in an age of global shipping.

The trouble with normal is it always gets worse

Being a colony in the American Empire has given Puerto Rico certain privileges among its Latin American and Caribbean neighbors (US citizenship, for instance, allows islanders to live and work on the mainland without being subject to the terrorism of Immigration and Customs Enforcement). But, it has also meant that, in spite of millions of dollars of “investment” in Puerto Rico by the US government and its corporations, only a tiny fraction of that money has lead to lasting improvements in the nation’s economy or infrastructure for its citizens.

A black-and-white rendering of the flag that represents Puerto Rico’s quest for sovereignty, by La Puerta

Instead, the island has been used as a vehicle for US capital to multiply itself by legal and less-than-legal means, as a source of cheap labor, and as a tourist destination. The island’s much tut-tutted government corruption, so often blamed on a cultural deficiency, is, in reality, a highly functional and orchestrated part of its manipulation as a colony. Corruption, after all, works really well if you have the money to navigate it, and American corporations certainly do.

So when the American economy hit hard times, they hit Puerto Rico even harder. In the 1990s the Clinton government ended a series of incentives that had drawn American corporations to the island.

The bursting of dot-com bubble, followed by the economic impacts of the 9/11 attacks also led to a worsening situation and, by the mid-2000s, Puerto Rico was borrowing more and more money to maintain its budget. At the same time it was cutting taxes, attacking workers’ rights, privatizing services and land and expanding commercial infrastructure in the hopes of luring back American investors.

Because Puerto Rico is essentially a colony, and because of its unique constitution, its government bonds are uniquely appealing, triple tax-exempt, attracting financial corporations who can therefore afford to make bigger loans and take higher risks. Indeed, the country’s constitution also promises bond-holders (largely major American financial corporations but also some members of the island’s middle-class) will be paid before any other state obligations are met, including spending on education or pensions. All this made the country’s debt extremely appealing to speculators.

One might speculate, too, on a degree of moral hazard: lenders know on some level that the American government will not allow the territory to simply default on and walk-away from the loans. Puerto Rican Politicians, eager to curry favor with both foreign capital and impress the local population with charismatic and spectacular mega-projects, were eager to borrow, even when loans became predatory with rising rates of interest and increasingly usurious conditions.

Facing a growing economic and debt crisis, Puerto Rico (like the ill-fated Greece) has been unable to do what has long been a solution for sovereign nation-states: devalue local currency. Rather, a series of elite neoliberal politicians sought to borrow their way out of the crisis and sweep the magnitude of the debt under the rug.

By 2014, it had become clear that the country was impossibly indebted and was unable to make interest payments, let alone pay back the loans. The Governor announced as much in 2015, triggering a minor financial panic and a series Congressional actions in Washington. By this time, much of the debt was held by so-called “vulture funds,” mostly headquartered in New York, that specialize in buying up the distressed debt of countries and companies for pennies on the dollar and then squeezing out all the interest payments they can, even while acknowledging the principle of the loan will never be repaid in full. This cruel method recently led to major showdown with Argentina and is, for all intents and purposes, the same maneuver of the notorious sub-prime loans of 2007/8.

In June of this year, Congress and various pro-capitalist forces in Puerto Rico responded by navigating a tangled web of contradictory political and financial forces to pass the PROMESA bill. This bill is aimed (allegedly) at “protecting” Puerto Rico from the vulture funds who otherwise could have, it is argued, frozen the island’s assets and brought its economy to an absolute standstill. For a country with only two weeks worth of food and completely dependent on imports, this would be a humanitarian nightmare.

Yet PROMESA is far from a benevolent gift and even its proponents in Puerto Rico admit it was a brutal compromise. It allow for a new wave of cuts to public services, a steep drop in the minimum wage and new forms of privatization. On top of that, it also institutes a Fiscal Control Board to oversee the island’s finances, which in both theory and effect negates the Puerto Rican government’s sovereignty.

This, combined with the court-case mentioned above, has left the island nation reeling. Times are already hard, but they’re about to get worse. Puerto Rico was already being transformed into a neoliberal utopia and a playground for American tourists and capitalists. These processes are now set to accelerate.

But unlike the halcyon days of 90s and early 2000s neoliberalism, no one in their right might believes this economic pain will bring future prosperity. As with elsewhere, it will be austerity unto death.

Spirits and arts of resistance

Of course, the spirit of Puerto Rican resistance remains strong, but there is no clear way forward. For decades the political scene has been dominated by the debate between neoliberals who affirm the status quo (maintaining the “special relationship” between Puerto Rico and the US) and neoliberals advocating for annexation and the birth of Puerto Rico as the 51st state of the Union. The generally left-wing Independence movement, which has had spikes in popularity and has also given rise to organizations using political violence, remains a distant third option according to opinion polls, though these may be deceptive.

While just under half Puerto Ricans live under the poverty line, and while unemployment is twice the US national average, many islanders look to the fate of other Caribbean and Latin American nations and have a hard time imagining their lot would be better as an independent country. With half of Puerto Ricans living in a diaspora of mainland American cities, the prospect of independence leaves a lot of unanswered questions. A series of plebiscites about the nation’s future over the past decade have been highly ambiguous, but generally favored either the renegotiation of the present Commonwealth status or official annexation and statehood.

Yet the recent legal interventions by the White House to insist Puerto Rico is a territory (read: colony), and the financial crisis and the false PROMESA bill may once again fan the flames of discontent. This is the hope of the street artists working at midnight.

“We want people to see it and realize they can’t just sit there and complain and wait for their problems to be fixed,” one local artist explains. “Do something. It doesn’t have to be marching in the streets – although of course, yes, we need to do that too – it can be just talking to your friends and family.”

“We want people to see it and realize they can’t just sit there and complain and wait for their problems to be fixed,” one local artist explains. “Do something. It doesn’t have to be marching in the streets – although of course, yes, we need to do that too – it can be just talking to your friends and family.”

Symbolic protests matter in a country where, for a decade in the mid-20th century, under the notorious “Gag-Law,” it was forbidden to own or display a Puerto Rican flag. Still today, the hue of the blue portion of that standard has nuanced political importance. Politics and art here travel hand-in-hand and artists take their responsibility as public intellectuals seriously.

A few weeks ago this same artist collective created huge controversy when they painted matte black an iconic and photogenic door in Old San Juan (the heart of the tourist area) that was formerly emblazoned with the Puerto Rican flag. They have posted an open letter to Puerto Ricans and tourists alike, calling for solidarity against the “Junta” represented by PROMEZA’s Fiscal Control Board, calling attention to its authoritarian dimensions and the sacrifice of democracy on the altar of colonial capitalist accumulation.

The technique of using black paint to call attention to the lethal financial sabotage of the country has caught on, spawning copycat actions across the island and throughout the diaspora and waggish responses on social media.

These artists are from a younger generation eager to see new alternatives emerge from what has felt like a political stalemate of their parents. Inspired by the militancy of the Nationalist struggles of the past, they are furiously trying to hold open a space for something new and radical to emerge, though they can’t necessarily offer a roadmap to a better future.

In this sense, their actions and orientations echo those felt by young people around the world, from Greece to Hong Kong to Paris to New York City, who have known nothing except neoliberalism, debt, financialization and what cultural critic Mark Fisher calls “capitalist realism”: the grim insistence that we are at the “end of history” and that there is “no alternative” to the capitalist status-quo.

These stark but elegant murals open a portal into some other world, a mix of the past and the future, where “economies” are not just some punitive alien force that liquidates everything of value and pipes it off to the rich and powerful, but are the sum of people’s collective efforts and guarantee peace, autonomy, security and community.

Meanwhile, at the Federal Building to the South, across the historic San Juan bay, young Puerto Ricans have established an Occupy-style protest camp demanding the abolition of PROMESA. Like these artists, they’ll be up all night holding a space open for the unknown, sitting the long wake for a murdered future, rousing the spirits of the rebellious dead.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/black-flags-debt-resistance-americas-oldest-colony/