Photo: Defend the Right to Protest

The Irish water insurgency: no more blood from these stones

- February 6, 2017

Capitalism & Crisis

After the government tried to privatize and raise the costs of water, the Irish drew a line: “they are not going to draw any more blood from those stones.”

- Author

Cobh, the “Great Island” located just off Ireland’s Southern Coast, can be reached only via Belvelly Bridge, which was of strategic importance in 2014 when it became central to some of the most coordinated mass mobilizations that the island had seen in a long time.

When it became clear that the semi-state water company Irish Water was going to install household water meters in Cobh as it had done elsewhere already — meaning that Irish Water would come in with trucks, dig up sidewalks, hook up individual households with water meters and begin charging people for water — people revolted.

Standing guard on the mainland side of Belvelly Bridge, activists would text others standing guard at the other end of the bridge, alerting them to the approaching trucks and tracking the direction the trucks were taking. Many of the organizers were women, the elderly, and the unemployed — those who were at home during the day.

By the time the trucks arrived at their locations, people were often already waiting for them in groups, blocking the trucks’ entry into the estates, or crowding around them and imprisoning the workers. People simply would not budge. Women, men and children locked arms and sang. Blockages lasted for hours, sometimes even days, which meant getting organized into shifts and holding nightly meetings about everything from what to wear to who would collect the children from school and make food.

By the time the trucks arrived at their locations, people were often already waiting for them in groups, blocking the trucks’ entry into the estates, or crowding around them and imprisoning the workers. People simply would not budge. Women, men and children locked arms and sang. Blockages lasted for hours, sometimes even days, which meant getting organized into shifts and holding nightly meetings about everything from what to wear to who would collect the children from school and make food.

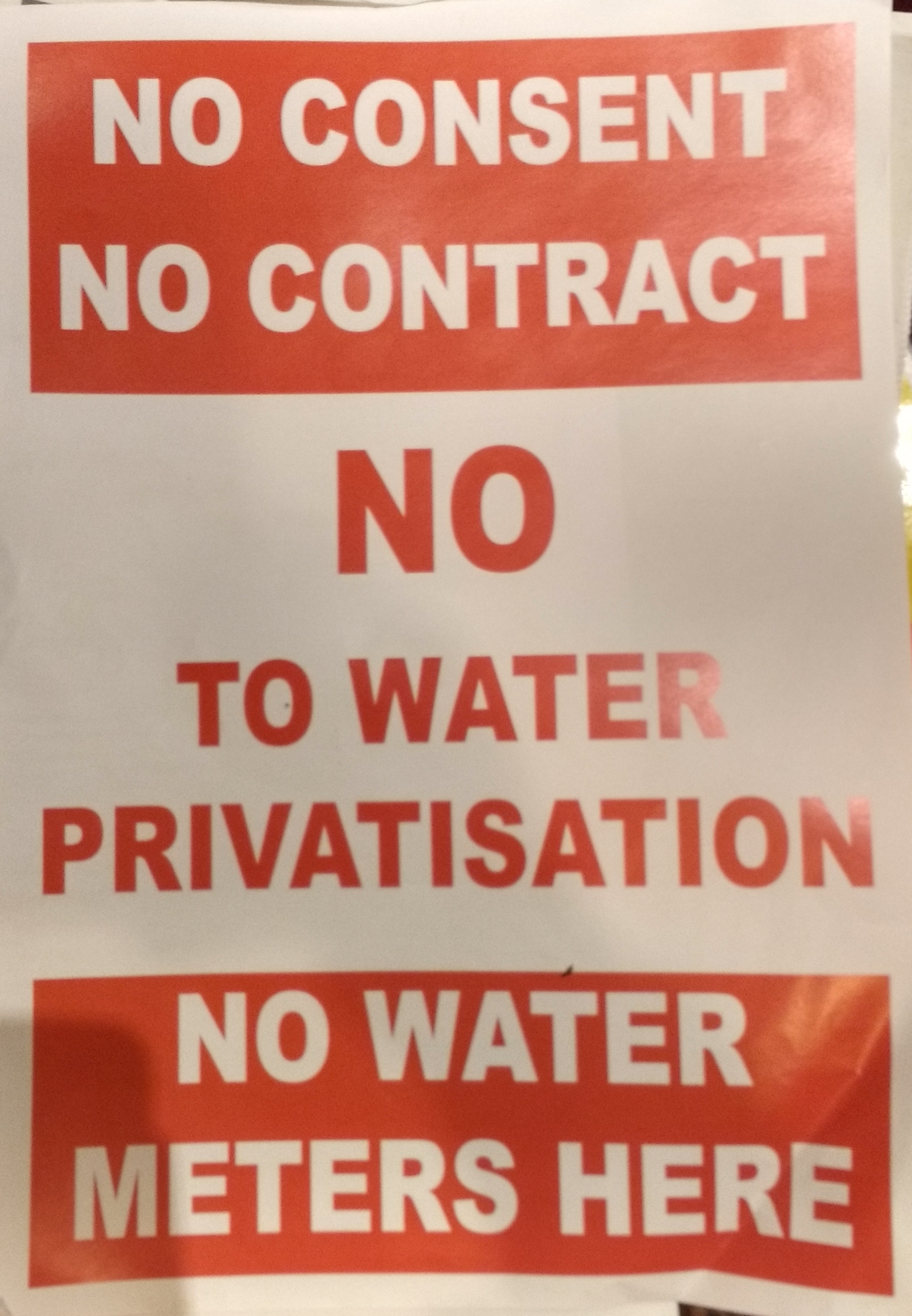

People set up tents and the estates started to compete with each other about who could make the best stews and sandwiches to feed the protesters. Striking red and white posters were stuck in windows that said “No Consent. No Contract. No to Water Privatization. No Water Meters Here.” As one water activist put it to me:

People had each others’ backs. Many of the working-class estates, not just in Cobh but all over the country, were in complete lockdown. We simply wouldn’t let Irish Water in. Communities, so alienated from each other and broken by poverty, evictions, unemployment, came together. It was magic.

Mass Mobilizations against Austerity

Cobh is just one example of the sustained mass mobilizations that austerity-ridden Ireland saw in the years 2014 and 2015. The installation of water meters and the prospect of Irish households being saddled with yet another bill led to intense and still ongoing protests, with the people of Ireland telling politicians and Irish Water that they could just “Stick Their Water Meters Up Their Arse.”

Hundreds of mainly working-class communities engaged in coordinated acts of mass civil disobedience, blocking trucks and demonstrating in several enormous national demonstrations. The water insurgency gained momentum so quickly that Irish Water workers routinely came flanked with police protection to fend off and sometimes also beat the crowds that sat, lay, or stood, often for hours, on sidewalks and streets as they blocked the meters. Elderly ladies brought out folding chairs and sipped their cups of tea as they sat on sidewalks, while younger men blocked the holes the company had already dug.

Activists argued that water had up to that point been considered a public good for which they paid through general progressive taxation, meaning that low-paid workers, the unemployed and the most vulnerable would not pay as much as the very wealthy. Adding an additional bill to what people were already paying would mean that they would pay for water twice.

Activists also tore into the ecological arguments made by Irish Water. In fact, metering would not automatically lead to the conservation of water since the Irish use on average 15-25 percent less water than the U.K., where water charges have existed since 1989. The water charges were thus by far the most contentious austerity measure imposed on Irish citizens since Ireland’s 2008 economic crash.

After a 70 billion bank bailout, which has been called “the costliest banking crisis in advanced economies since at least the Great Depression,” paid for with taxpayers’ money and resulting in large public-sector salary cuts, the reduction of welfare and social spending, and an increase of regressive taxes and user fees, the water charges were what the people called the straw that broke the camel’s back — a moment where they shouted: “You are not getting any more blood from these stones.”

The Privatization of Water

Irish Water was founded in 2013 in response to Ireland’s massive fiscal crisis following the bank bailout. The creation of this nominally public but in fact public private partnership (PPP) or, as it is called in Ireland, a Design-Build-Operate (DBO), is part of a global trend where austerity-starved governments seek to invest in ailing infrastructure by accessing loans directly through global investors, including banks, pension fund managers and elite private equity firms.

The design of this state-corporate form allows for new debt to be moved off the public balance sheet and for government spending to be deferred because payments are made somewhere down the road when the project is completed. As one Canadian report put it, governments “are essentially ‘renting money’ that they could borrow more cheaply on their own because it’s politically expedient to defer expenses and avoid debt.”

Research in Canada has further shown that PPPs in fact cost an average of 16 percent more than conventional public provisioning, not only because private borrowers need to make a profit but also because they usually pay higher interest rates than governments do. Transaction costs for lawyers and consultants also add to the final bill, as the Irish know all too well. The cost of these expensive projects are, in Ireland as elsewhere, downloaded onto “end-users” — the very people who can afford it the least.

Money for water infrastructure investment is easy to come by these days. A huge global liquidity bubble is intersecting with the growing anticipation that water is rapidly emerging as one of the most lucrative commodities on the planet. Public water works like Irish Water are thus prime targets for the “new water barons” who have rushed to invest in water not just because it is so lucrative, but also because water is considered to be a low-risk investment. As a non-optional service basic to human life, water is, as one London-based analyst at HSBC Securities put it, “inflation-proof and there’s no threat to earnings, really. It’s very stable and you can sell it anytime you want.”

This intimate relationship that has emerged “between the flows of water in Irish taps and the flows of money in global financial markets” has therefore meant that unmetered water needs to be transformed into a “predictable, well-performing asset circulating in secondary financial markets.” Whatever flowed out of taps had to be rendered countable and measurable so that it can be made subject to speculation. Hence the installation of water meters, and hence the ire that the Irish reserved for this small, seemingly innocuous technical device.

Until today, one might be lucky enough to run into a water meter fairy — clandestine guerrilla plumbers who have in the last years un-installed hundreds of meters across the country; meters that are symbols of plunder but also objects to be laughed at — photographed in unlikely places such as beaches and posted on Facebook or exhibited publicly in little front gardens.

Local protests against water meters in 2014 spread like wildfire from places like Dublin, Cork, Cobh, Ballyphehane and Bray and were buoyed by already existing anti-austerity groups such as Dublin Says No. First arrests were made of citizens who had refused access to Irish water workers by blocking off roads with their cars.

By late 2014, Right2Water was founded, a national umbrella organization supported by trade unions, left-leaning political parties and a variety of community groups and activists. What followed were several riveting national days of action that saw tens of thousands of people demonstrate in the streets of Dublin — the last of which was held on September 17, 2016, and which drew an estimated crowd of 80,000.

To this day, many Irish working-class estates are barely metered. Others only half, with small groups of activists such as one in Ballyphehane still patrolling the streets in bright yellow reflecting jackets that signal their continued vigilance. Two-thirds of the members of parliament who were elected into office in March 2016 stood on an anti-water charges platform. Over half of these politicians are not paying their water charges and insist, instead, on general progressive taxation.

The water charges have since been suspended for nine months, and an Independent Water Commission set up by the Irish government recently concluded that water charges should be scrapped altogether, that water should be paid for through general taxation, and that the Irish overwhelmingly insist on water being a public good — publicly owned and managed. It’s a massive victory for Irish water protesters that the government-appointed commission confirmed in almost every single respect what they had been saying all along.

Social Contract vs. Household Contractualization

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, middle and especially lower-income households have suffered increasingly under what some have called household contractualization, meaning that they have increasingly had to enter contracts with private or partially privatized corporations and therefore pay more for the basic social reproduction of the household (gas, electric, water).

These household payments on utilities such as energy, water and phones (but also on insurance, rent, healthcare and loans for housing, education and vehicles) are increasingly bundled up and traded on global markets. They have thus become central to an intensifying frontier of capital accumulation and “anchors” to which the global financial system is attached.

The financialization of household assets is felt particularly strongly in countries like Ireland, which was already saddled with the bank bailout that came with a whole plethora of new taxes and charges for citizens. There had therefore already been a number of previous rumblings in Ireland in 2012 about the inability of low-income households to pay a new household charge that was supposed to be an interim measure for future property taxes, a measure Dublin had agreed to under its European Union and International Monetary Fund bailout program.

But it was the looming water charges where the Irish drew the line. By refusing the contract and insisting on paying for water through general progressive taxation, the Irish did something incredibly radical for our times: they refused the very mechanism — the contract and bill — through which households are made subject to the logics of financialization. “No Consent. No Contract. No to Water Privatization. No Water Meters Here,” as the posters stuck to windows read.

The people of Ireland instead insisted on a very different contract altogether — a social contract where the state would commit to just, progressive taxation. This was a demand for the state to turn away from its current model of dealing with crippling sovereign debt through the short-sighted sell-off of its vital services and to instead re-think the collective fiscal arrangement and its futures: Who pays what kinds of taxes? And what what happens with these taxes?

This was not a “nostalgic vision” of the state-managed model of the past, but a demand for novel and progressive forms of public financing. It is no wonder that the Irish water insurgency has repeatedly been compared to the famous water wars in Cochabamba, Bolivia. The Irish drew a line and were ready to put their bodies on that very line. Irish Water is not going to draw any more blood from those stones.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/ireland-anti-austerity-water-protests/