Photo: mali maeder from Pexels

Offshore finance: how capital rules the world

- February 8, 2019

Capitalism & Crisis

The rise of offshore finance is not solely about capital moving to banks in exotic islands, it is also about the creation of a two-tier global system.

- Authors

Capitalism only triumphs when it becomes identified with the state, when it becomes the state.

— Fernand Braudel

Following the election of Donald Trump and claims of Russian meddling during his campaign, a privatization deal of Russia’s state-owned oil company Rosneft caught the media’s attention: despite sanctions, some €10 billion had been invested in Rosneft via a Singapore-based shell company, representing a 20 percent stake in the oil giant.

Rosneft argued that the investment was a simple joint venture between the Qatari Investment Authority and Swiss oil trader Glencore, but the numbers simply did not add up. Yet there is no way of knowing who owns the Rosneft stake, because the ownership is hidden in a Cayman Island’s shell company.

“Like many large deals, the Rosneft privatization uses a structure of shell companies owning shell companies” across offshore jurisdictions. In this case it left a dead-end paper trail from Qatar and Switzerland to a company in Singapore, which is owned by a London-based firm, itself controlled by a mailbox in the Caymans, registered at the address of a prestigious law firm. Although the deal remains a mystery, it shows how the rich and powerful hide and transfer their assets, including large transactions of geopolitical significance, in complete anonymity.

This essay focuses on the murky financial realm known as offshore finance. It shows that offshore finance is not solely about capital moving beyond the reach of states, but involves the rampant unbundling and commercialization of state sovereignty itself.

Offshore jurisdictions effectively cultivate two parallel legal regimes. On the one hand, we have the standard regulated and taxed space for domestic citizens in which we all live, on the other we have an “extraterritorial” secretive offshore space exclusively maintained for foreign businesses and billionaires, or non-resident capital, comprising “a set of juridical realms marked by more or less withdrawal of regulation and taxation”.

This offshore world is a state-created legal space at the core of the global financial system, and hence global capitalism, housing the world’s major capital stocks, flows and property claims with the goal of protecting wealth and financial returns. Viewed as an integrated system, it is a curious sovereign creature capable of exerting a political-economic authority similar to imperial powers of the past.

Some call it Moneyland, others see a return to feudal times. The offshore world could also be compared to the two-tiered architecture of imperial Panem in Suzanne Collin’s dystopian Hunger Games trilogy, which is said to reflect the workings of the Roman empire.

Specifically, the present international system of states might be compared with Panem’s troubled “districts”, where ordinary citizens are territorially enclosed and forced to pay hefty “tributes”, while the exclusive offshore world resembles aspects of Panem’s mighty capital city — the Capitol — where its affluent ruling class are exempt from austerity, taxation and authoritarian rule, living from the wealth created by others.

We focus on so-called offshore financial centres (OFC) as the building blocks of offshore finance. These centers are defined as “a country or jurisdiction that provides financial services to nonresidents on a scale that is incommensurate with the size and the financing of its domestic economy”.

Besides functioning as tax havens or secrecy jurisdictions, OFCs are used as platforms for acquiring debt, structuring funds, company formation, investment protection, and so forth. Depending on the definition, up to 100 jurisdictions worldwide can be classified as OFCs. These might function as “conduit” and “sink” jurisdictions, intermediate or final destinations for mobile capital.

As OFCs increasingly cultivate niche strategies, their subcategories have become ever more specific: while some are focused on providing secrecy and wealth protection to conceal illicit money, others cater for corporations and banks seeking “light touch” regulatory stepping stones to arrange global financial flows. The budding variety in specializations complicates a uniform comparative framework to study distinctive offshore centers. Notwithstanding these differences, the essential fact is that offshore finance ultimately constitutes a globally integrated space operating beyond the control of any individual state.

This essay details the history, geography, mechanisms, enablers and inhabitants of the offshore world. Our account shows how the global economy is manufactured through national politics or, to paraphrase the erstwhile Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt, how the economic world of property (dominium) is built through political sovereignty (imperium).

This focus also allows us to counter the idea that the many nationalists currently rising across the world are “challengers” to the global order. On the contrary, our counter perspective considers the global rise of authoritarian nationalism to be a logical continuation of the neoliberal project.

Understanding how financial power is typically fused with, and ultimately couched in, state power also means rethinking ideological divides between public and private spheres; between political and economic domains; or between state and market. For in the offshore world — the mighty Capitol of our age — financialized and hypermobile global capital effectively is the state.

A short history

Although tax evasion and asset protection occurred in ancient times, the Middle Ages and beyond, the global rise of offshore finance coincided with a number of late nineteenth-century legal innovations.

Notably, the birth of the private corporation as “natural person” is traced back to this period, as leading capitalist states liberalized the right to incorporate a company — a right which until then was exclusively chartered by sovereign decree. This development ignited the rise of large multi-national corporations (MNCs), which challenged the emerging inter-national legal order in which states wield exclusive territorial power.

The tension between national territorial “enclosure” and global capital mobility, increasingly organized via complex multinational corporate structures, triggered additional legal innovations. In particular, the creation of mailbox or shell companies, i.e. legal entities with no substantial material presence, opened Pandora’s box, as MNCs could henceforth locate themselves in another jurisdiction without physically relocating their actual activities.

The right of incorporation, in other words, quickly turned into fictional bookkeeping devices.

Another crucial building block underpinning offshore finance was the bilateral allocation of tax rights between states, anchoring capital mobility in a set of tax treaties during the 1920s that distinguished between a host country — the jurisdiction of economic activity — and a home country — the domicile of the owner, investor or corporate headquarters.

This arrangement separated tax rights along the lines of capital-importing and capital-exporting countries, reflecting power relations at the time, with the United Kingdom and the United States as leading capital exporters. These principles remain fundamental to today’s bilateral patchwork of more than 3,000 tax treaties, enabling the contemporary offshore world to mature.

Although the post-war era was initially defined by an international regime in which states exerted considerable control over their domestic economies, requiring capital controls to curtail cross-border finance, the late 1950s saw the first cracks in this regime, heralding a key moment in the global ascent of offshore finance. In 1957 the Bank of England decided that foreign currency exchange between non-resident lenders and borrowers was not subject to its domestic supervisory oversight and regulations, such as capital requirements.

This accounting gimmick heralded the birth of the Eurodollar markets, which made lending US dollars more profitable in the offshore City of London than on Wall Street, leading to US banks and others setting up shop in London. In creating an unregulated “stateless” space for cross-border capital markets, the Bank of England aimed to revive the sterling area following the decline of the British empire. This soon led its remaining crown dependencies and overseas territories to gradually transform themselves into tax havens, with the City at the center of an emerging global offshore grid.

In parallel, decolonization saw leading capitalist states create a global patchwork of bilateral investment treaties, further securing cross-border investments and investor rights, chiefly to the benefit of MNCs headquartered in rich countries holding assets across their former colonies.

For example, decolonization led the Netherlands to incorporate a novel investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) clause in its bilateral investment treaty with Indonesia, devised for Dutch corporations to protect their assets. Today, more than 3,000 bilateral investment treaties contain ISDS clauses, making the Netherlands not only a tax haven, but also a major claim haven for global corporations using Dutch shell companies to protect their investments.

The stunning growth of the Eurodollar markets eventually undermined the post-war order, which collapsed during the early 1970s. Fixed exchange rates made way for floating rates, introducing novel financial risks for corporations, governments and households, accelerating the spectacular rise in financial derivatives trading in Chicago, London and New York.

Burgeoning capital mobility led to the creation of transnational marketplaces, increasingly built via offshore entities and structures posing difficulties for national regulators. The ascent of neoliberalism in the 1980s streamlined the rise of globalizing finance: besides deepening bilateral fixes, capital mobility became increasingly anchored in multilateral trade agreements and organizations, encouraging ever more states to deploy unilateral strategies to attract hypermobile capital.

As a result, capital flowing into and out of offshore jurisdictions mushroomed over the 1990s, and truly exploded during the 2000s. Figure 1 shows the gross inward and outward capital flows via Dutch shell companies. The Netherlands is currently the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI), operating as the world’s major intermediary offshore destination for global capital. The value of gross transactions grew from €782 billion in 1996 to €2.2 trillion 2002, rising to a whopping €7.4 trillion in 2017. These spectacular growth rates suggest that offshore finance is no longer an exotic sideshow alongside regular and regulated finance, but has become the new normal.

Figure 1:

A new dawn

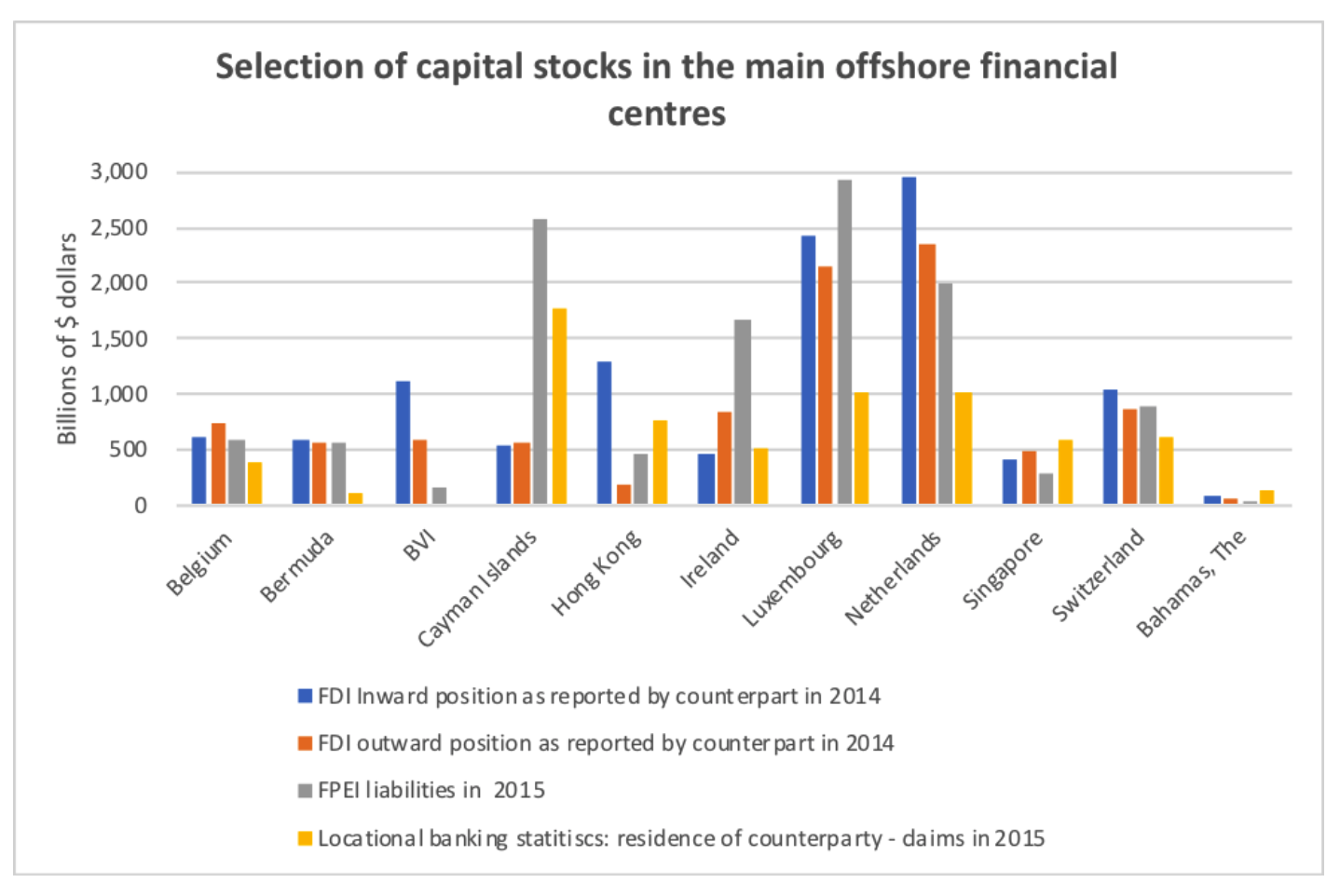

In an OFC ranking that will be published in 2019, we identify a core group of OFCs that structurally capture the largest share of offshore capital stocks and flows worldwide. As the central offshore grid underlying the world’s leading financial centers — London and New York — we rank these OFCs according to their use by investment funds, MNCs and banks. In rank order, our core group consists of the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, Bermuda, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Ireland, the Bahamas, Singapore, Belgium, the British Virgin Islands and Switzerland.

This outcome is not surprising, as it confirms what different studies by academics, policymakers and civil society organizations (CSOs) have shown. Table 1 shows the size of the different stocks of capital accumulated in these offshore centers. The figures on inward and outward FDI, foreign portfolio investments (FPI) and banking statistics show different channels and logics orchestrating offshore financial flows: where the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg are prime destinations for the financial flows of investment funds and banks, Luxembourg and the Netherlands are key gateways for MNCs.

Table 1:

Together, this group comprises the world’s major conduit and sink destinations, offering secrecy, tax-minimization, incorporation mechanisms, and a range of specialized services.

For instance, Ireland is dedicated to corporate head offices whereas the Netherlands facilitates holding companies. These differences are often in symphony, resulting in popular tax-planning structures such as “the Double Irish with a Dutch sandwich”. The group is spread across the world’s major markets and time zones: where Hong Kong is the offshore gateway into and out of China, Ireland and the Netherlands typically serve the global operations of US multinationals.

What further stands out is the geographical prominence of Europe, specifically the (former) territories of the British Empire, followed by a central role for the Low Countries — Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Overall, corporate value chains are habitually structured along this group, which together with the wealth of the world’s billionaire class effectively constitutes the backbone of global capitalism.

Although governments and legislators initiate and enact offshore legislation for individual OFCs, the integrated offshore world is effectively cultivated by a handful of globally-operating banks, law and accountancy firms — curiously, three professions all licensed by the state (or central bank) to perform specific public functions.

The recent streak of offshore data leaks provides fascinating insights into their activities: Swiss Leaks uncovered a massive tax-evasion scheme run by the Swiss subsidiary of the global bank HSBC, and the Panama Papers unveiled the tricks of global law firm Mossack Fonseca in Panama, manufacturing the shell companies through which HSBC clients evaded tax. Lux Leaks, in turn, exposed corporate tax-avoidance schemes enabled by the Luxembourg authorities and accountancy giant PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Through the dedicated assemblage of hybrid loans and entities certified by government tax rulings — corporate funding structures that are fiscally or legally treated differently across jurisdictions, capitalizing on mismatches in tax codes — corporations enjoyed “effective tax rates of less than one percent on the profits they have shuffled into Luxembourg”.

The Paradise Papers, centred on the Bahamas office of offshore law firm Appleby, reveal that the core operating system of offshore finance is a highly exclusive world, anchored in a dozen OFCs cultivated by a handful of professional intermediaries, structuring the “activities” of their corporate clients across OFCs to maximize wealth protection and returns.

Together with the global billionaire class, who are the ultimate beneficial owners of this corporate edifice, “these players have become, as it were, citizens of a brave new virtual country” Again, their composition is truly global: from European royals to American nouveaux riches; from Chinese princelings and Arab princes to Russian oligarchs and African warlords — the global elite has effectively carved out a secretive, tax-free and sovereign homeland for itself.

Sovereign capital

Over, under and beside the state-political borders of what appeared to be a purely political international law between states spread a free, i.e. non-state sphere of economy permeating everything: a global economy.

— Carl Schmitt

Although offshore finance has only recently matured and professionalized, the mechanisms underlying its global rise to prominence remain the same as a century ago. The offshore world evolved on the back of the international state system, where the sovereign is regarded the highest legal authority.

That is to say, under the guise of public international law states are free to open up their domestic economies to foreign capital via bilateral and multilateral means. Capitalist states have used this freedom to facilitate capital mobility, which is the key prerequisite for offshore finance to flourish, for it makes little sense to unilaterally attract foreign capital in a world of strict capital controls. Friedrich Hayek compared the vital capitalist right of capital mobility to “the xenos, or guest friend, in early Greek history”.

Quinn Slobodian argues that:

The category of xenos rights helps us think about individuals having protected rights to sage passage and unmolested ownership of their property and capital, regardless of the territory. It is a right that inheres to the unitary economic space of dominium rather than the fragmented state space of imperium — yet it requires the political institutions of imperium to ensure it.

It is here that we stumble upon the realization that ideological splits between political and economic domains make little sense, as offshore finance is woven from the sovereign fabric of states, anchoring the capitalist world of property (dominium) through the rampant commercialization of state sovereignty (imperium).

Consequently, no single state can meaningfully control contemporary offshore finance since the introduction of regulation in one place will result in capital moving elsewhere.

Interestingly, there are clear historical precedents for the present geography of financial power. Looking at the birth of modern capitalism, for example, Arrighi argued that “the Genoese merchant elite occupied places, but was not defined by the places it occupied”, constituting a “non-territorial” infrastructure similar to the offshore “Eurodollar market”.

In other words, modern capitalism simultaneously developed in the space-of-places where it became tied to particular states, and the space-of-flows encompassing networks above the control of any state.

Where the Dutch Republic and Britain effectively operated company states, representing a relative unity between state and capital embodied in their quasi-sovereign East India companies, since hegemonic power shifted to the United States, privatized corporate power has relentlessly globalized and intensified, with the sovereignty undergirding globalizing corporations increasingly scattering across the world.

In the words of Arrighi, pointing to the decomposition of territorial sovereignty, the “explosive growth of transnational corporations … may well have initiated the withering away of the modern inter-state system as the primary locus of world power”.

To grasp how capital rules the world, we need to systematically distinguish between formal and effective sovereignty, and realize that corporate power is always derived from state power. The sovereignty underpinning offshore finance might be compared to Berle and Means’ classic account of the modern corporation, emphasizing the separation between corporate ownership and control.

In a similar fashion, sovereignty ownership and control seem to have diverged: where the former remains the realm of imperium proper, chiefly the national state, global sovereignty control has progressively shifted towards major corporations and their professional gatekeepers maintaining the offshore space of dominium, of property.

Although OFCs legally place non-resident financial activities outside territorial boundaries, indeed offshore, this remains within the confines of their sovereign authority: although lawmakers are territorially bound, the sovereignty for sale is of an extraterritorial nature.

Crucially, used as a single package by global corporations and elites, the many slivers of commercialized sovereignty available across the world combine, fuse and ultimately mutate into “a new global form of sovereignty” — a deterritorialised sovereignty jointly underpinning the planetary rule of capital.

Challenging the Capitol

At the turn of the millennium, offshore finance became the engine room of global capitalism. Its spectacular growth is now tied up with wider financial and technological change, such as rampant corporate fictionalization, seeing corporations assume ever more financial traits, driving the rise of non-regulated, non-bank, market-based finance, which is chiefly orchestrated offshore.

Likewise, banks and financial institutions have collectively entered this shadowy financial world, which is legally viewed as distinct from regulated banking and finance, yet the 2008 financial crisis revealed that these two worlds are intimately connected, and effectively comprise a whole in which the offshore component dominates. Indeed, overall it is safe to say that “global finance” is offshore finance.

These changes have unfolded in a wider process of incessant neoliberalization, having accelerated global income and wealth inequality, as the rich and powerful can now simply choose whether or not to pay taxes, which often is perfectly legal.

It is this very development which undermines the social fabric of society, effectively bisecting it, as elites increasingly evade their public duties, having legally detached themselves and their properties from their respective countries of origin, as if they lived elsewhere, or nowhere at all. It is these developments which have driven popular resentment throughout the world, with a rising number of nationalists vowing to ‘drain the swamp’.

Unfortunately, given that the offshore dominium undergirding global capitalism is primarily built through the national politics of imperium, the idea that nationalists will “take back control” from the globalists is debatable.

Offshore finance is built out of the unilateral commercialization of what mostly constitutes national sovereignty in order to attract capital principally mobilized via a global web of bilateral tax, trade and investment treaties. In other words, present-day global capitalism, captained by trillion-dollar corporations and the billionaire class, does not necessitate a multilateral order — far from it, as it thrives on sovereign borders and related legal mechanisms of exclusion.

Summarizing recent developments, Slobodian argues that:

the formula of right-wing alter-globalization is: yes to free finance and free trade. No to free migration, democracy, multilateralism and human equality.

Indeed, global capitalism adores national sovereignty, and merely despises its popular democratic foundations and applicability, which decades of neoliberalism have systematically corroded. The present rise of illiberal forces, therefore, might not prove a rupture to the established order, but rather anchor its global dominance, as “political illiberalization might equally shield the economic core of the neoliberal project from popular resistance, effectively functioning as its toxic protective coating” — not least to safeguard the offshore world of property.

A quick look into the data leaks mentioned earlier reveals that most authoritarian “strongmen” themselves have secured their assets and incomes offshore, along with a sizeable faction of the global billionaire class who sponsor them. Cynically, the same is true for the global media barons having supplemented their neoliberal narratives with nativist venom, selling the virtues of patriotism while themselves living as true “citizens of nowhere”, owning multiple passports to minimize the taxes on their vast business interests structured offshore.

The rise of Bolsonaro or Trump, the advent of Brexit — on closer inspection these and other political developments driven by “dark money” suggest an offshore billionaire’s rebellion rather than a people’s anti-establishment revolt.

Meanwhile, even the chairman of the high church of neoliberalism — the World Economic Forum (WEF) — is semantically distancing himself from “globalism” to better accommodate “national interests” under globalization, notwithstanding the fact that global capitalism built by and for the offshore billionaire class annually congregating in Davos simply rages on like before.

Looking at what has euphemistically been labelled Alt-right, moreover, we find a vulgar celebration of unrestrained corporate power behind a facade of “refreshing” memes and cultural narratives, revealing a remarkable continuation of neoliberalism in general and a radically deepening of corporate sovereignty in particular.

For their ideal capitalist state fully rejects the premises of liberal democracy, seeing presidents replaced by CEOs running their states as corporations, maximizing shareholder value for their ultimate beneficial owners: the global billionaire class.

Under what thinkers like Nick Land and Curtis Yarvin label Gov-Corp, politics is deemed illegal and citizens are stripped of their rights — the only human right will be “exit” for those who can afford it, meaning capital flight, upholding the cast-iron right of capital mobility. In what can only turn into an endless race to the bottom, future Gov-Corp states will forever compete for hyper-mobile offshore capital.

Notwithstanding populist appeals of popular democracy, the aim of these self-proclaimed challengers to the global order is to reach neoliberalism’s final frontier: the full corporate takeover of sovereign governments and states themselves.

Although this prospect has yet to materialize, contemporary capitalism is increasingly turning into a global platform economy, with offshore finance as its central operating system and the rest of the world plugged into its dominant operating logic on various terms.

Where ordinary citizens and businesses are subject to global capitalist rule via their respective states — enforcing austerity, taxes and, increasingly, authoritarianism — offshore residents have grown above territorial enclosure, having effectively become a global “stateless” oligarchy, living secretive and tax-free lives with their vast fortunes supported by expansionary monetary policy.

Representing the very crown of capital’s defeat of labor, the offshore world is threatening to give rise to an age of ultra imperialism, as an increasing number of states have effectively joined in an offshore federation, “replacing imperialism by a holy alliance of the imperialists”.

The offshore world already operates as a global incorporated Leviathan, as the world’s ultimate creditor state, with a handful of global banks, law and accountancy firms “seeing like a state“. In this capacity, moreover, these (para-) financial players wield classic hegemonic power elsewhere, exerting “functions of leadership and governance over a system of sovereign states”, as clearly exemplified throughout the financial crisis, where they advised clueless governments to bail out the troubled offshore portfolios of the few at the price of austerity for the many.

We have reached the point, like in the Hunger Games trilogy, where citizens across the “districts” of the world need to rise up and unite against the Capitol of our age — the offshore world — threatening to transform the international system of states into a present-day Panem, enforcing its global rule through local strongmen.

Citizens worldwide need to reclaim democratic oversight over what constitutionally is — or should be — popular sovereignty. This will require exposing nationalist nostalgia, sugarcoated with xenophobia, as hyped-up distractions from the power grab by the offshore Capitol. It will need a spotlight on global corporations and elites avoiding public responsibility and scrutiny who urgently need to be relieved from the vast political power they enjoy and exert.

Although the fight will prove difficult, with no quick fixes, it offers a narrow political target to mobilize a broad political base, one that can bring together the indignant and deplorable, uniting red squares, green ambitions and yellow vests. For only a truly collective struggle to dethrone offshore finance opens up possibilities to really take back control.

This essay is part of the Transnational Institute’s “State of Power 2019” report.

Read Nick Buxton’s introduction here, and you can find the full report here.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/offshore-finance-capital-rules-world/