Photo: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutterstock.com

Pro-Kurdish HDP fights an uphill battle in Turkey elections

- March 27, 2019

Land & Liberation

In Turkey’s increasingly repressive political climate, the HDP is facing off against the ruling AKP in a battle for the Kurdish vote at local elections.

- Author

This Sunday, on March 31, Turkey will be holding local elections, marking the fifth election in as many years. Turkey’s economy is facing severe troubles: high inflation and a weak Turkish lira are eroding the sense of economic security the country has enjoyed since the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002.

The AKP continues its close alliance with the far-right Nationalist Action Party (MHP). In most provinces and districts, the two parties will be supporting a joint candidate. The opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the Good Party (IP) will also support joint candidates, including for the municipalities of Istanbul and Ankara, the country’s two main cities. Through such close cooperation, the opposition hopes to put a dent in the AKP’s authoritarianism and begin steering Turkey towards normalcy.

For the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the stakes are even higher. Its main objective is to take back control over the municipal and district councils won in 2014 but taken over by government-appointed “trustees” in 2016. Despite the ongoing state repression, the HDP is expected to perform strongly and to gain back the control of many, if not all, of the provinces and districts in the Kurdish majority eastern and southeastern provinces.

The HDP chose not to field candidates in most of western Turkey and has been encouraging its voters to back the opposition’s candidates in an attempt to weaken AKP’s power base.

By focusing its energy and attention on its traditional power bases in the country’s Kurdish regions, the HDP appears to be returning to the strategy pursued by pro-Kurdish political parties in the 1990s. This strategy enabled the Kurdish movement to establish a strong presence in the region. Having an institutional base there since 1999 enabled it to introduce measures to develop Kurdish culture and campaign for a democratic and peaceful solution to the conflict.

Given the intense repression the HDP has faced since the summer of 2015, it has little choice but to consolidate its support base in the Kurdish heartlands. Regaining control of the local councils will add a much-needed thrust to its struggle for peace and democracy in Turkey.

A brief history of Kurdish local representation

Turkey’s transformation into a multi-party democracy in 1946 created opportunities for Kurds to engage in politics. Center-right parties keenly nominated influential Kurdish tribal and religious leaders as their candidates in parliamentary and local elections hoping to win the support of Kurdish voters. With the rise of the Kurdish movement from the mid-1970s onwards, the power of the Kurdish traditional elites began to weaken and a more diverse group of Kurds began to engage in politics.

In the late 1970s, when pro-Kurdish candidates won the municipal councils of Diyarbakır, Batman and Ağrı, the state cracked down. One month after his election in 1979, Edip Solmaz, the new mayor of Batman, was murdered, while his colleague, Mehdi Zana, mayor of Diyarbakır since December 1977, was arrested in 1980 and imprisoned for over a decade.

Since 1990, Kurdish political representation took a new turn with the establishment of the People’s Labor Party (HEP), the first openly pro-Kurdish political party in Turkey. The founding of the HEP provided Kurds with a legal means of political representation and an important channel to voice their demands.

During the 1991 parliamentary elections, the HEP managed to get 22 of its candidates elected by running on a shared ticket with the Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP). In 1993, Turkey’s Constitutional Court shut down the party and by 1994, its successor, the Democracy Party (DEP), was shut down too. Four Kurdish MPs – Hatip Dicle, Orhan Doğan, Leyla Zana and Selim Sadak – received 15-year sentences and six others left Turkey to escape imprisonment.

Following the elimination of the Kurdish parliamentary opposition, the next decade or so was spent re-building the pro-Kurdish democratic movement. These efforts were led by the People’s Democracy Party (HADEP), which, by the end of 1990s, managed to establish an organizational network across Turkey. At the local elections in 1999, the HADEP won a total of 37 municipal and districts councils across the majority Kurdish regions, but it too was shut down in 2003.

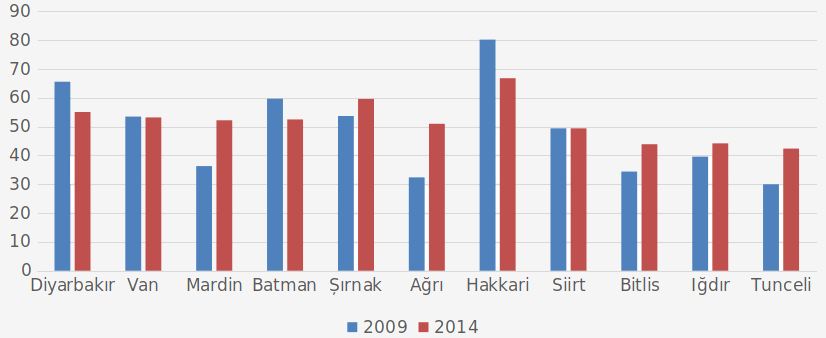

In 2004, the DEHAP — successor to HADEP — increased the number of the councils under their control to 57. The upward trend in the support for the pro-Kurdish movement continued in 2009, with the Democratic Society Party (DTP) — yet another reincarnation — establishing itself as the leading party of the Kurdish regions by winning more than 50 percent of the votes in many of the provinces and districts and gaining control over 99 councils. In 2014, the pro-Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) consolidated its position as the leading party of the Kurdish regions and won a total of 102 councils.

The percentage of votes the DTP and BDP obtained in the local elections in Kurdish majority provinces in 2009 and 2014, respectively.

Running many municipal and district councils in the Kurdish regions since 1999 enabled the pro-Kurdish movement to establish a strong regional presence and strengthen its bonds with different sections of the Kurdish society.

Such an institutional base allowed the pro-Kurdish parties to challenge the homogenizing policies of the state by promoting the use of Kurdish language and establishing cultural associations. Over the past decade, pro-Kurdish political parties have also adopted measures promoting gender equality by introducing a system of co-leadership, where each executive position of the party is shared between a man and a woman.

The HDP’s rise and the ensuing backlash

Since the mid-2000s, local successes of pro-Kurdish parties started to be mirrored at the national level. In July 2007, Kurdish representation in parliament returned with the election of 22 DTP MPs who ran as independent candidates in order to bypass the exceedingly high 10 percent electoral threshold. At the 2011 general elections the number of pro-Kurdish MPs increased to 35.

The institutional base built by the pro-Kurdish parties at the local level combined with parliamentary representation paved the way for the HDP to take part in the June 2015 elections as a party, instead of putting forth independent candidates. It won a historic 13 percent of the popular vote and 80 seats in the parliament. The HDP’s success meant the ruling AKP lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since it came to power in 2002. After failing to form a coalition government, new elections were announced for November 2015.

During the summer of 2015, the AKP government escalated the conflict with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) guerrillas. Its harsh approach to the Kurdish movement enabled it to consolidate its Turkish nationalist base in the November 2015 elections. As a result of the much-changed domestic context, the HDP’s share of the popular vote fell to just below 11 percent, securing only 59 parliamentary seats.

In the first half of 2016, Turkish army and security forces began targeting the PKK’s urban strongholds in the southeast of Turkey, leading to the destruction of large parts of Diyarbakır’s old city, Șırnak, Cizre and Nusaybin and hundreds of military-enforced curfews in dozens of towns. The heavy-handed crackdown resulted in many civilian casualties, widespread human rights violations and forced displacement of an estimated half a million Kurds.

The government also took steps to eliminate the institutional base the pro-Kurdish movement managed to construct at the local and national levels. In May 2016, the parliament passed legislation to remove the legal immunity of MPs, which was supported by the opposition CHP and opened the way for legal proceedings against HDP MPs.

The failed military coup on July 15, 2016 — widely believed to have been carried out by officers close to the exiled cleric Fethullah Gülen — provided the ideal pretext for the AKP government and President Erdoğan to further weaken the opposition and undermine democratic institutions. In the summer of 2016, the AKP government forged a close alliance with the far-right and ultranationalist MHP, putting the marginalization and repression of the pro-Kurdish movement at the heart of their alliance.

In early November 2016, 11 HDP MPs were detained; nine of them remain in custody, including HDP’s former co-presidents, Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ. Several former HDP MPs are serving jail sentences, including Idris Baluken, who, on January 4, 2018, received a sentence of 16 years and eight months. In addition, several former HDP MPs left Turkey to Europe in order to avoid imprisonment.

The exact number of the HDP members currently under arrest or in custody is not known but party estimates put the figure around 6,000. The arrests of HDP’s local leaders has continued throughout the election campaign. This is not the first time the Turkish state has taken repressive measure against the pro-Kurdish democratic movement, but the sheer numbers involved mark this as a new low in a long history of political repression in Turkey.

The government also targeted local-level representation of pro-Kurdish parties, and in August 2016, it passed a decree that enable the removal of elected mayors from office, replacing them with appointed trustees (“kayyum” in Turkish).

Except for the Iğdır municipal council, which remains under the control of the Democratic Regions Party (DBP), HDP’s regional ally, the remaining 10 municipal councils, 72 district councils and 12 town councils have all been take over by a government-appointed trustee. In total, 94 of the 102 councils that were under control of the DBP were taken over. Ninety-three of the DBP co-mayors have been detained since September 2016, and by the end of 2018, a total of 53 remained under arrest. Several co-mayors have been convicted and are serving jail sentences, including the co-mayor of Diyarbakır, Gültan Kışanık.

The cultural programs and projects set up by the municipalities were among the main targets of the appointed trustees. The use of community languages in the activities of municipal councils was ended and Kurdish-language signs and nameplates were removed. Schools and nurseries providing Kurdish language education were closed and the monuments symbolizing important dates and events in Kurdish history were removed. Women-empowerment services introduced by the councils over the past decade have all been discontinued.

Turkey’s political focus in 2017 turned to a referendum to change the system of government to an executive-style presidency, which President Erdoğan has pursued since 2014. The AKP’s proposed reforms were able to pass through parliament with the support of the MHP. The 18 constitutional amendments needed for the executive-style presidency were put to a referendum on April 16, 2017 and narrowly passed amidst widespread intimidation and irregularities.

Despite widespread and persistent repression, the HDP still obtained nearly 12 percent of the vote at the June 2018 general election, securing 67 seats in parliament. In the presidential election held on the same day, the HDP’s imprisoned former co-president Selahattin Demirtaş won over 8 percent of the votes cast, indicating that the HDP is likely to perform well in the upcoming elections.

A chance for a new beginning

In most predominantly Kurdish provinces, the race is between the AKP and the HDP, and opinion polls predict a win for the HDP. The HDP have fielded a number of strong candidates, including current or former MPs and former co-mayors alongside activists of the women’s movement and trade unionists who have a strong connection to the local communities. Some candidates have been active in pro-Kurdish political circles for a long time and their seniority indicates the importance the party attaches to these local elections. The HDP also boosted its chances by forming an alliance with several other Kurdish political parties.

Under normal circumstances, the DBP should be running in the municipal elections, but state repression has dismantled its party organization in most provinces. The HDP’s decision to take part in the local elections and concentrate its efforts in the southeast comes down to the conditions it finds itself in. It does not represent a departure from its long-term objective of being a party for all of Turkey.

For Kurdish voters, the election is taking place in an emotionally charged context: Kurdish MP Leyla Güven has been on hunger strike since October 31, 2018, demanding the end of the isolation of imprisoned Kurdish leader Abdullah Öcalan. The hunger strike has a lot of support among the Kurdish movement, with many activists both in Turkey and abroad starting hunger strikes of their own. Turkish security forces continue to violently repress any actions in solidarity with Güven and the other hunger strikers.

The HDP is promising to turn municipal and district councils into platforms for addressing concerns of the local community, combating inequalities and promoting multiculturalism. It says it will reverse all the decisions taken by the trustees: their immediate plans include re-opening the educational institutions for Kurdish-language education and refuges that provided shelter to women experiencing domestic violence. Supporting cultural centers for the arts and associations combating poverty are also high on the agenda, as are steps to strengthen the local economy and policies to advance gender equality and promote women’s full participation in decision making processes at the local level.

The usual concerns about voter registration irregularities and the threat of electoral fraud persist. The mainstream media continues to exclude the HDP in their coverage of the elections and President Erdoğan has frequently describing the HDP leaders as “terrorists” and as Turkey’s internal enemy. The election is not expected to be free or fair, but whether the manipulation and intimidation will be sufficient to stop the HDP remains to be seen.

If elected, the HDP co-mayors will face strong challenges in their efforts to exert their power. According to a report prepared by the DBP, around 2,000 officials of the municipal councils were removed from their position by the trustees and replaced by AKP loyalists. Also, the HDP co-mayors will be under increased state scrutiny as Erdoğan promised to continue his policy of replacing them with appointed trustees.

Nevertheless, in the short term, winning back the municipalities in the Kurdish region will boost the morale of the party’s support base and strengthen the HDP’s efforts to counter the government’s depiction of it as an illegitimate political movement. It will also increase the relevance of the HDP in the efforts to reverse the authoritarian turn in Turkish politics, particularly if its supporters help the opposition beat AKP candidates in the country’s key urban centers of Istanbul and Ankara.

A big win in the east will strengthen HDP’s support base and enable it to rebuild its organizational networks and take steps towards addressing the destruction caused by the state’s repression in the past three years.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/pro-kurdish-hdp-fights-uphill-battle-turkey-elections/