Boiling Point

As with so many crisis-ridden countries, Turkey’s problem lies not in the country neglecting neoliberal principles, but in adopting them in the first place.

Neoliberalism’s Crumbling Democratic Façade

- Issue #4

- Author

Years from now, when we look back at the 2010s, what will be the images that come to mind? Will we recall the wealth and prosperity brought to us by free markets and private investment? The freedom and democracy we enjoyed under our neoliberal governments? Or the ways in which we bravely protected our cultural and natural heritage, safeguarding it for future generations?

Most likely not. When we think of the 2010s, we will remember the protesters in the streets, the wars ravaging the Middle East, causing entire populations to leave home and hearth behind, and the millions of people across the globe risking their lives just to make a living somewhere else. We will remember the xenophobic attacks, the racist politicians, the gag orders and the crackdowns. But perhaps most of all, we will look back in disbelief, unable to understand how we could idly stand by and witness the slow but steady destruction of our planet — blindly burning, digging and slashing our way beyond the point of no return.

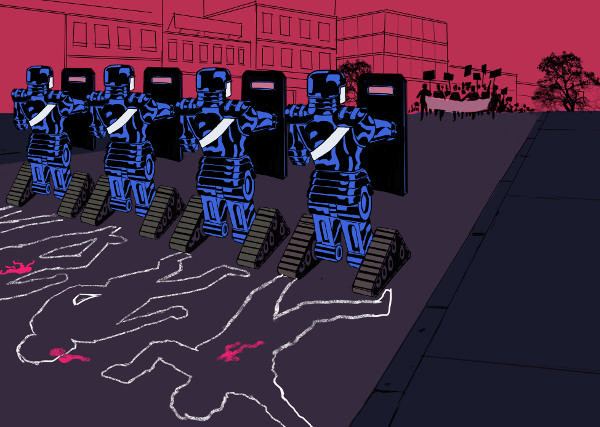

To be sure, the state’s response to the global financial crisis has been swift and determined: banks were bailed out, protesters beaten back and border fences put up. The economic recession, the popular uprisings and the increasing political instability of recent years encouraged neoliberal governments around the globe to discard their democratic pretenses and let their authoritarian nature to come to the fore. These developments have been particularly acute in Turkey, whose anti-democratic turn in recent years provides one of the most striking examples of authoritarian neoliberalism. As a strategic NATO ally, a former Islamic darling of the West and a long-time contender for EU membership, Turkey’s current state of emergency is in fact not the exception, but the rule pushed to its natural extreme.

To be sure, the state’s response to the global financial crisis has been swift and determined: banks were bailed out, protesters beaten back and border fences put up. The economic recession, the popular uprisings and the increasing political instability of recent years encouraged neoliberal governments around the globe to discard their democratic pretenses and let their authoritarian nature to come to the fore. These developments have been particularly acute in Turkey, whose anti-democratic turn in recent years provides one of the most striking examples of authoritarian neoliberalism. As a strategic NATO ally, a former Islamic darling of the West and a long-time contender for EU membership, Turkey’s current state of emergency is in fact not the exception, but the rule pushed to its natural extreme.

Turkey’s Boiling Point

The curtain first began to fall on Turkey’s neoliberal success story in the summer of 2013, when the Gezi protests combined with intensifying economic pressures to produce a powerful catalyst for the country’s authoritarian turn. Since then, the violent escalation of the Kurdish question, rising tensions with the Gülen movement and the attempted coup d’état of July 2016 appear to have driven these developments to their logical conclusion: the move towards an authoritarian state presiding over the steady erosion of hard-fought social rights and political freedoms.

Back in 2013, the millions of people who expressed their discontent with the government during the Gezi protests caught Erdoğan’s AKP-led government by surprise. Until then, the AKP had been all but basking in praise and support, enjoying a privileged position as the West’s Muslim prodigy in the region, working hard and successfully to tick all the boxes and join the neoliberal club of capitalist democracies. What it had failed to recognize was that more and more people felt like their neighborhood, city and society was no longer theirs; they had become strangers, outsiders in their own lives, victims of the structural violence that had bulldozed their homes, taken away their jobs, destroyed their theaters, cut their trees and killed their hopes.

Faced with a significant share of the population that refused to buy into the neoliberal myth of progress and prosperity the government responded in the only way it knew how: it sharpened the bayonets and launched a war on its own people.

More and more people felt like their neighborhood, city and society was no longer theirs; they had become strangers, outsiders in their own lives, victims of the structural violence that had bulldozed their homes, taken away their jobs, destroyed their theaters, cut their trees and killed their hopes.

After a very violent police crackdown on the street protests — in which hundreds were arrested, thousands were injured and over a dozen protesters were killed, including the 15-year-old Berkin Elvan — the state then continued its repression in less overt but no less authoritarian ways. Activists, artists and academics who had expressed support for the protests were accused of supporting terrorism, and in many cases charged as such. Teenagers were sent to jail for posting a tweet, and teachers lost their jobs for trying to analyze and discuss the social relevance of the largest popular uprising in the country’s history in their classes.

Many foreign observers have described the violent response of the Turkish state as the AKP’s “authoritarian turn.” While it is true that the government acted in a more authoritarian manner than before the Gezi uprising, it would be misleading to present this development as a break with the past. The post-Gezi crackdown and subsequent political repression did not constitute a breaking point with the past, but a boiling point — the culmination of many years of structural violence and oppression, which have long been so characteristic of neoliberal regimes across the globe.

Freedom-loving “Terrorists”

In the years since Gezi, the reach of state control has expanded dramatically, while civil liberties and freedom of speech have been curtailed and the general state of the economy has continued to decline. Meanwhile, Turkey’s Western allies have failed — or refused? — to intervene or speak up in name of the values they profess to hold dear.

Even as the Turkish state massacred its own people in the predominantly Kurdish southeast, NATO jets continued to take off from Turkish airbases to launch bombing campaigns against the so-called Islamic State in Syria. While hundreds of thousands of Kurds fled their homes, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel paid a friendly visit to President Erdoğan to discuss a highly controversial refugee deal that effectively appointed Turkey as the regional gatekeeper of Fortress Europe.

In the summer of 2015, the war between the Turkish state and the Kurdish PKK escalated anew, barely two months after the leftist Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), with its roots in the Kurdish freedom movement, had booked a historic victory in the general elections by passing the exceptionally high 10 percent parliamentary threshold.

The two events were intricately linked. The pragmatist AKP had never really seen the country’s oppressed Kurdish minority as anything but an electoral asset, and the AKP’s earlier attempts at brokering peace with the PKK had never come from a sincere intention to address the Kurds’ long-standing grievances relating to the historical denial of social, cultural and political rights. Rather, its rapprochement with the Kurds stemmed from a belief that the only thing required to solve the Kurdish question was to turn them into model citizens in the neoliberal sense of the word — indebted, enslaved and forever precariously employed. In the post-2013 context, however, the AKP came to realize that it had more to gain politically from appealing to its nationalist constituency and attacking the Kurds, than by continuing to try to resolve the Kurdish issue.

The pragmatist AKP had never really seen the country’s oppressed Kurdish minority as anything but an electoral asset.

Ever since this shift in political strategy and the escalation of the war with the PKK, the Turkish state has shifted its authoritarian drive into second gear. In an attempt to legitimize its full-fling crackdown on all forms of political dissent — whether in the press, in the streets or through a simple petition — the government has resolved to frame anyone who dares to disagree with its policies as a “terrorist.” The HDP leadership has since been jailed and thousands of the party’s cadres have been detained, arrested, fired from their jobs or forced to flee abroad. All stand accused of “abetting terrorism,” or in other words, of having demanded the official recognition of Kurdish rights and culture.

The failed coup attempt in the summer of 2016 has provided the AKP with the necessary pretext to purge tens of thousands of civil servants, judges, lawyers, teachers and security personnel from its ranks. Over a hundred media outlets have been closed down, and in its December report the Committee to Protect Journalists claims that 81 journalists are currently in jail in Turkey — a number local activists claim is even higher. All in all, Turkey, a country that was once hailed as an example to its neighbors of what an Islamic democracy could look like, has come to rely on increasingly harsh methods of state repression to strengthen the ruling party’s grip on power and supposedly protect the country from “disaster.”

Staring into the abyss

The Turkish case shows us what lurks behind the fairytale façade of neoliberalism, and what happens when its authoritarian nature comes back to the fore. Turkey’s adoption of neoliberalism as its guiding principle on the one hand allowed for the country’s political and financial elites to build, bet, bulldoze and brawl to their heart’s delight, and on the other it threw up a smokescreen of high growth rates and profitable investment opportunities that permitted business to continue as usual without outside intervention.

Ian Bruff writes in his introductory essay that “neoliberalism is about the creation and maintenance of the kinds of markets that it wishes to see, with a central role accorded to the state in this process.” Perhaps Turkey takes us even a step further: in successfully creating and maintaining the “kinds of markets it wishes to see” the neoliberal Turkish state grows ever more dominant — both vertically, in its relations with its own citizens, and horizontally, with respect to other countries. The neoliberal state turns into an ever more controlling entity at the command of its ruling elite. If these elites then happen to be xenophobic populists with an authoritarian streak, it will not be long before the country finds itself staring into the abyss.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/neoliberalisms-crumbling-democratic-facade/

Next Magazine article

Black Awakening, Class Rebellion

- Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, George Ciccariello-Maher

- December 18, 2016

Algorithmic Control and the Revolution of Desire

- Alfie Bown

- December 18, 2016