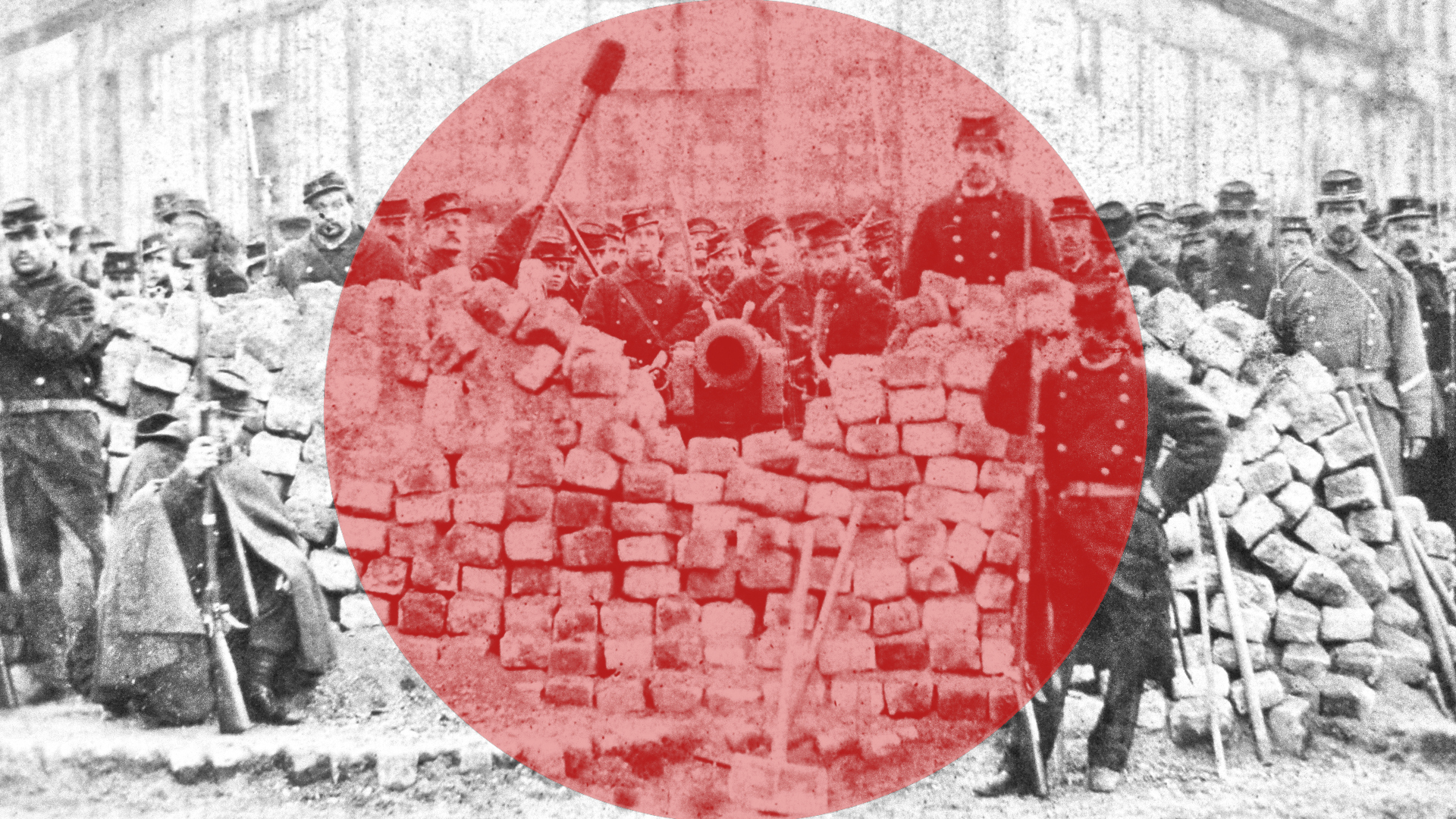

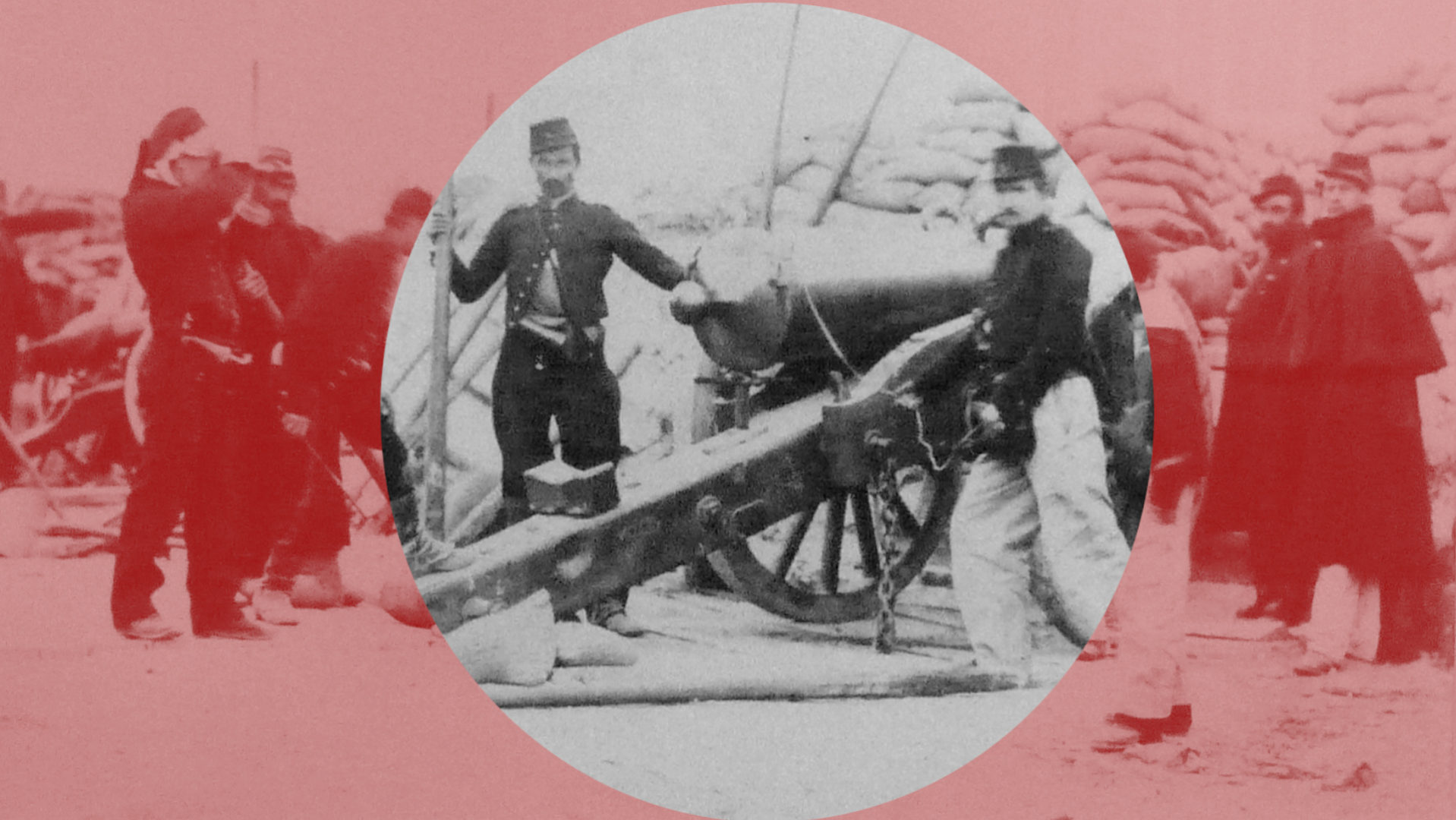

From the very first days of its short-lived existence in 1871, exactly 150 years ago today, the revolutionary Commune of Paris has occupied a central place in the radical imagination of the international left. For the Communards themselves, the revolution did not end, but rather began at the city’s limits. In their perception, the founding of the Commune in Paris was but a first step towards the building of the Universal Republic: a Commune of Communes encompassing the entire globe and uniting all peoples in a confederacy of liberatory democracies.

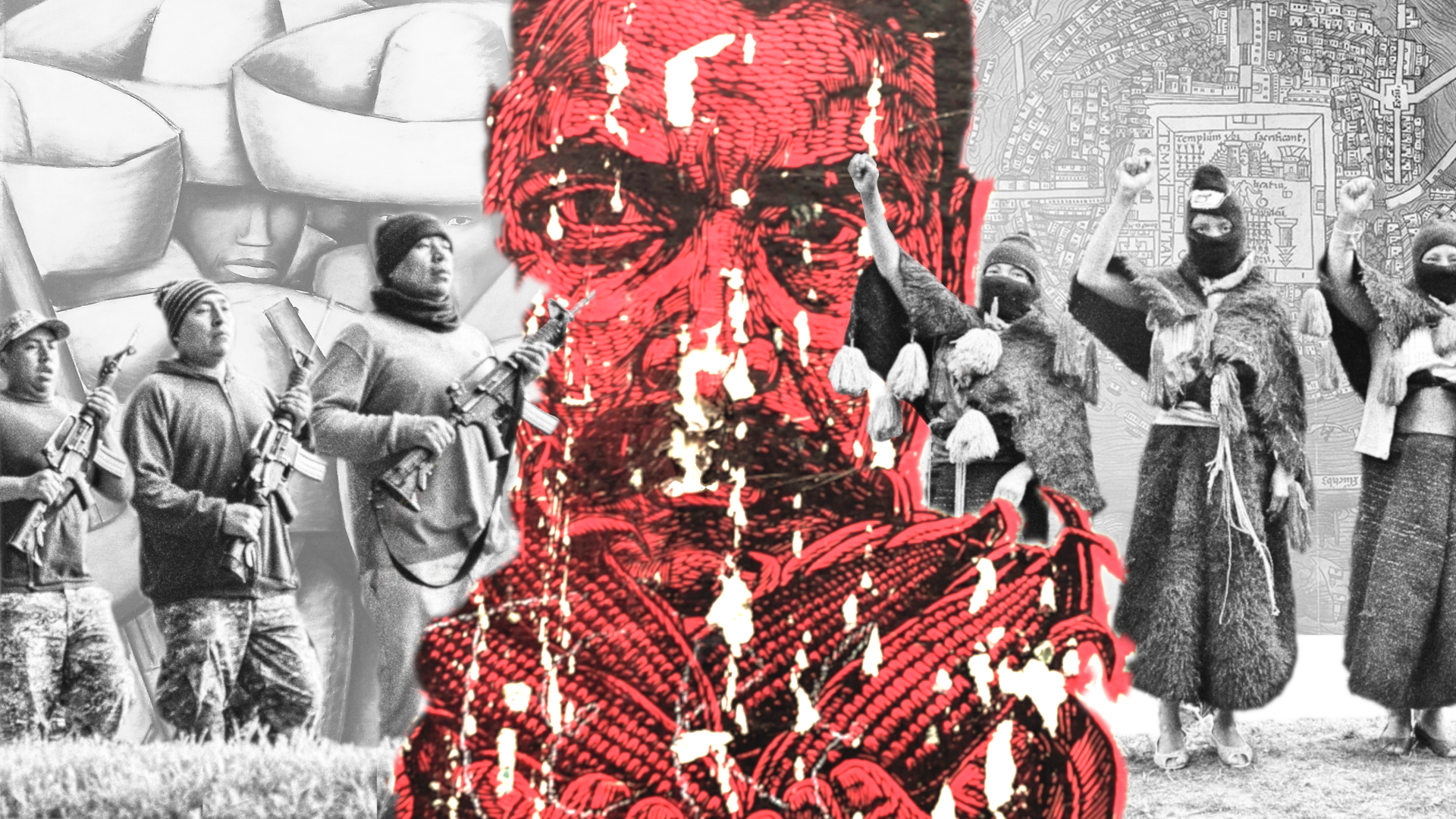

ROAR places itself firmly in this tradition. Our first print issue, “Revive la Commune!”, was entirely dedicated to the revival of the commune in the 21st century, both in spirit and in practice. Now, on the 150th anniversary of this historic chapter in revolutionary history, we once again turn to those fateful 72 days between March 18 and May 28, 1871, to draw the necessary lessons from the Communards’ heroic struggle for freedom and democracy and to explore the forms and ideas in which the Commune lives on today.

This page will be regularly updated with new essays and content until May 28.