Race and Policing

With the rise of neoliberalism, the state — and especially the police — has developed new, more subtle articulations of racism while entrenching existing racial inequalities.

The Dog-Whistle Racism of the Neoliberal State

- Issue #4

- Author

Photo: Alisdare Hickson

Cockroaches, swarms and sexual predators — just some words that have been used to describe migrants in the British press. A 60 percent increase in hate crimes since Brexit, particularly towards Muslim women, has left many feeling that anti-racism is failing us. Compounded by a Trump victory in the United States, post-Brexit Britain is ringing with echoes of the 1970s, when fascist groups such as the National Front and the violence they peddled were a daily reality for Britain’s black and South Asian communities.

Pushing the far-right to the peripheries of political debate can provide some respite from the overt bigotry and violence we associate with it. But state institutions, particularly the police, have developed new ways of articulating racism. As anti-racism gained traction in the 1970s, overt bigotry became increasingly marginalized. But by borrowing ideas from the US, a “neoliberalized” racism emerged in Britain, where the state increasingly employed dog-whistle racism while entrenching existing racial inequalities.

New Ways of Articulating Racism

One way of reproducing neoliberal racism is through the way crime is depicted. In the United States, “muggings” became a term used by government and police to describe street crimes they associated with young black men. This racial trope soon spread to Britain. The moral panic around the black mugger was famously deconstructed by Stuart Hall and his colleagues in Policing the Crisis in 1979. Their analyses showed how the press, government and police developed a racist “moral panic” surrounding young black men in urban areas. This moral panic led to the “sus” laws, which enabled officers to stop and search any individual they suspected of committing a crime.

The resultant police powers, which did not require reasonable suspicion, were disproportionately used against black people, and led to the urban revolts across cities in England in 1981. Hall and his colleagues demonstrated how racist language could be shifted away from familiar bigotry towards racialized tropes that framed targeted groups as deviant. It was part of the prelude to neoliberalization, which ushered in an environment where overt racism became framed as running counter to the meritocracy of the market. Distortions to this meritocratic Britain (a black minority) must be repressed in order to protect the freedoms of others (the white majority). It is through this logic that neoliberalism was able to remain simultaneously committed to both the emergent entrepreneurship of the so-called free-market and the racialized social control of the pre-neoliberal era.

The resultant police powers, which did not require reasonable suspicion, were disproportionately used against black people, and led to the urban revolts across cities in England in 1981. Hall and his colleagues demonstrated how racist language could be shifted away from familiar bigotry towards racialized tropes that framed targeted groups as deviant. It was part of the prelude to neoliberalization, which ushered in an environment where overt racism became framed as running counter to the meritocracy of the market. Distortions to this meritocratic Britain (a black minority) must be repressed in order to protect the freedoms of others (the white majority). It is through this logic that neoliberalism was able to remain simultaneously committed to both the emergent entrepreneurship of the so-called free-market and the racialized social control of the pre-neoliberal era.

The latest permutation of this black folk-devil is the gangster, and it has shaped the anti-crime rhetoric of government and the increasing power of police in Britain over the last decade. Like the racist trope of the mugger, this has been intensified by comparable moral panics around gangs in the US, where the term is also used to criminalize black people and articulate a dog-whistle racism. This was put to use following police killings of African Americans, such as the case of Antoine Sterling, who was identified as a gangster with a criminal history by police and the press.

Prime Minister David Cameron declared an “all-out war on gangs and gang culture” in the summer of 2011. Media outlets played images of burning buildings and masked youths on a seemingly continuous loop. In the midst of the panic were the images of Mark Duggan, a man of African-Caribbean heritage from Tottenham in North London. According to the police, he was wanted, armed and one of the 48 most dangerous gangsters in Europe. The month of August that year saw the most widespread instance of civil revolts seen in England for 30 years. Over 2,000 arrests were made and countless raids, stops, searches and other instances of police violence and harassment ensued.

In the wake of the unrest, both the state and corporate media outlets alerted the public to a moral crisis. Responding to the unrest, David Cameron identified a “gangster culture” with which he was determined to go to war. Yet even those belligerent comments appear almost mild compared to the bigotry and racial hatred that was released post-Brexit. While the language of “swarms” and “cockroaches” has been routinely denounced by the left, the comments made by the police and David Cameron about “gangs” in the summer of 2011 received much less criticism. Rather than identifying black people overtly, police and government used covert racist language, a dog-whistle racism, to communicate a racist message. While Brexit has certainly intensified racism in Britain today, understanding the seemingly unspoken racisms in the undercurrents of neoliberal policies and rhetoric can offer us a possible way forward in tackling racism both old and new.

The Biggest Gangs in London

Neoliberalism has simultaneously presented itself as an economic project and as a withering away of racialized inequalities through the meritocratic nature of the market. Conservative and centrist policymaking identifies crime, particularly violent crime, lack of households with male breadwinners, lack of strict discipline and moral values, and lack of work ethic as the root causes of social ills. The black conservative tradition has a significant support base in the United States, from Booker T. Washington to Bill Cosby and Ben Carson. Likewise, the intersection between black identity and conservative values has gained increasing influence in Britain over the past decade. While David Cameron was Prime Minister, his advisor on youth and crime, Shaun Bailey, wrote:

A culture of dependency rules the working class. The first wave of migrants from the West Indies never had this, they fended for themselves. My mom knew that she couldn’t cope with me and my brother when we were teenagers. But unlike other people she never acted as if it was society’s fault.

This neoliberal logic of hard work and meritocracy is coupled with a necessity for a more controlling state. Bailey goes on to claim: “At the moment prison is a boon because it is nice and boring. It encourages young people to be lazy.” It is within this climate of neoliberal rhetoric that state security became increasingly punitive. In the mid-1970s, the prison population in England and Wales was around 40,000, but by 2016 this figure had more than doubled to over 85,000. Black conservatives such as Bailey helped to legitimize not only the policing and imprisonment of working-class communities, but also the disproportionate impact that this neoliberal securitization had on black communities.

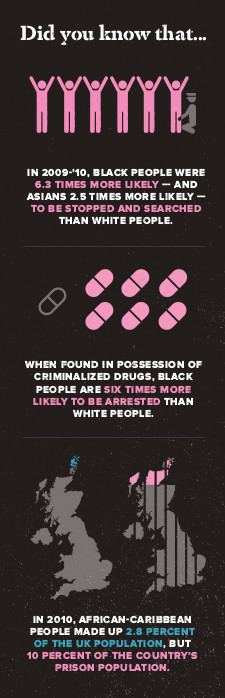

It is widely accepted that African and African-Caribbean people are disproportionately stopped and searched by police in Britain. The existing data show that in 2009-‘10, black people in Britain were stopped and searched for drugs at 6.3 times the rate of white people, while people identified as Asian were stopped and searched at 2.5 times the rate of whites. But it does not end here: when found in possession of criminalized drugs, black people are six times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts, and if found with cannabis, black people are five times more likely to be charged than white people.

It is widely accepted that African and African-Caribbean people are disproportionately stopped and searched by police in Britain. The existing data show that in 2009-‘10, black people in Britain were stopped and searched for drugs at 6.3 times the rate of white people, while people identified as Asian were stopped and searched at 2.5 times the rate of whites. But it does not end here: when found in possession of criminalized drugs, black people are six times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts, and if found with cannabis, black people are five times more likely to be charged than white people.

Black people are also over four times more likely than white people to be taken to court if found in possession of drugs; over four times more likely than white people to be found guilty in court; and five times more likely than whites to be taken into immediate custody. This disproportionality extends to other offenses too, black people being 38 percent more likely than white people to be sentenced to prison for public order offenses or possession of a weapon, with this figure rising to 44 percent for driving offenses.

These patterns of policing and court decision-making are evidence of institutional racism, as the normal functioning of these organizations produces (possibly unintended) racist outcomes. Unsurprisingly, this pattern of racial injustice is reflected in incarceration rates. According to the Equality and Human Rights Commission, figures in 2010 show that African-Caribbean people make up 2.8 percent of the UK population, but 10 percent of its prison population. Police in England and Wales also have a database of the DNA of everyone taken into their custody, including those eventually found innocent and even those wrongfully arrested. Roughly 10 percent of white males in Britain are currently on this DNA database, but this figure jumps to 30 percent for black British men.

In 2014, only 1 percent of the nearly 8,000 complaints of racism against police in England and Wales were upheld. A year later, London’s Metropolitan Police failed to uphold a single complaint of racism, claiming that such criticisms are generally “a simple misunderstanding or poor communication.” Reports from the Institute of Race Relations and Inquest found that 69 racially minoritized people were killed by the British state between 2002 and 2012, 18 percent of the total amount killed, despite constituting only 7 to 13 percent of the British population during that period.

In 2014, only 1 percent of the nearly 8,000 complaints of racism against police in England and Wales were upheld.

The Metropolitan Police have had a number of “gang” units, such as the “Trident Gang Crime Command,” which focused “primarily on gun crime and homicide within the black community” and which was responsible for organizing the killing of Mark Duggan in 2011. Conferences in London’s City Hall discussed the need for new approaches, weapons and powers to repress those identified as gang members. One example of such police advocacy saw a £1 million annual fund to provide, among other extended police and judicial powers, “dedicated gang prosecutors,” in order to ensure that those accused were more likely to receive a conviction.

A recent study found that, while 81 percent of the people identified as gang members in London are black, only 6 percent of the cases of serious youth violence (the crimes generally associated with gangs) in the capital are carried out by black people. In Manchester, in the north of England, the pattern is similar: 72 percent of identified gang members are black, yet they constitute only 27 per cent of those involved in serious youth violence. These police data show that, rather than gang members being identified with the crimes they are associated with, the most frequent correlation is that of race.

The press in Britain’s capital has been a key ally in reproducing the moral panic surrounding the “gang.” As part of its “Gangs of London” campaign, the London Evening Standard newspaper ran a series of headlines claiming: “Turf wars among London’s 250 gangs account for half of all shootings and a fifth of stabbings and have fuelled this epidemic of violence.” These sensational stories were published by both the police and the press in the same week as the inquiry into the killing of alleged gangster Mark Duggan. Readers were told that “these young gangsters have lost so many friends, they’ve stopped going to their funerals,” further devaluing black life in the weeks and months which coincided with the inquiry into the death of Mark Duggan.

In the end, there appeared to be no crimes linking Mark Duggan to being part of a gang. He had no serious criminal record, and was unarmed when shot dead as he stepped out of a minicab. While a gun was found 12 feet (4 meters) from his body, neither Duggan’s fingerprints nor his DNA could be found on it, and no witnesses (including the police), could explain how it got there. Despite this, Duggan’s killing was deemed lawful by a jury in 2014 — a conclusion no doubt shaped more by the moral panic of the gangster than by the evidence presented in court.

Beaten with a Blunt Implement

Operation Blunt 2 was a police operation that took place in London between May 2008 and April 2011. It was designed to combat the “gang” violence associated with gun and knife crime in the capital. The primary power used by police in this operation is called Section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 — a power for maintaining public order. The power was originally introduced for the policing of football matches, where police believed that there was a high likelihood of violence. It enabled police to designate any geographical area, like a football stadium and its surroundings, as an area in which they can stop and search any individual, without requiring reasonable suspicion. The powers were then extended to other contexts that the police identified as prone to violent disorder.

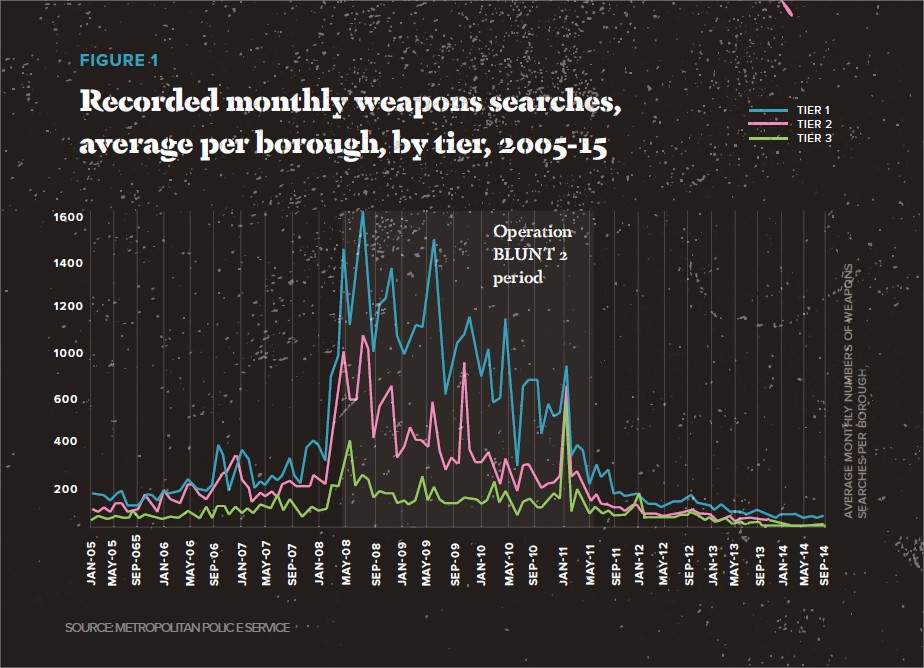

In 2008, the Metropolitan Police divided London into three categories: Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3. Tier 1 represented those boroughs which police intelligence indicated had the highest likelihood of gun and knife crime (not the boroughs with the actual highest levels of such crime). Section 60 stops were increased dramatically in these areas for the three years, during which Operation Blunt 2 took place. Tier 2 boroughs were deemed less at risk, and so Section 60 stops were increased slightly. Tier 3 boroughs were identified as posing no serious threat, and Section 60 stops and searches were not increased in these areas. Figure 1 gives an idea of how much the use of Section 60, the power to stop and search an individual without requiring reasonable suspicion, increased over the course of the operation.

In 2008, the Metropolitan Police divided London into three categories: Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3. Tier 1 represented those boroughs which police intelligence indicated had the highest likelihood of gun and knife crime (not the boroughs with the actual highest levels of such crime). Section 60 stops were increased dramatically in these areas for the three years, during which Operation Blunt 2 took place. Tier 2 boroughs were deemed less at risk, and so Section 60 stops were increased slightly. Tier 3 boroughs were identified as posing no serious threat, and Section 60 stops and searches were not increased in these areas. Figure 1 gives an idea of how much the use of Section 60, the power to stop and search an individual without requiring reasonable suspicion, increased over the course of the operation.

Within a year, the Metropolitan Police were celebrating the success of the campaign, identifying an 11 percent drop in gun and knife crime in the capital. The commander in charge of the operation commented:

We targeted the dangerous places where knife crime is most prevalent and young people are most concerned. Stop and search has helped create the environment where the carrying of knives is now less common than when we started. Seizures are substantially down despite maintaining the high level of activity. Officers carried out 287,898 stops and searches since May last year.

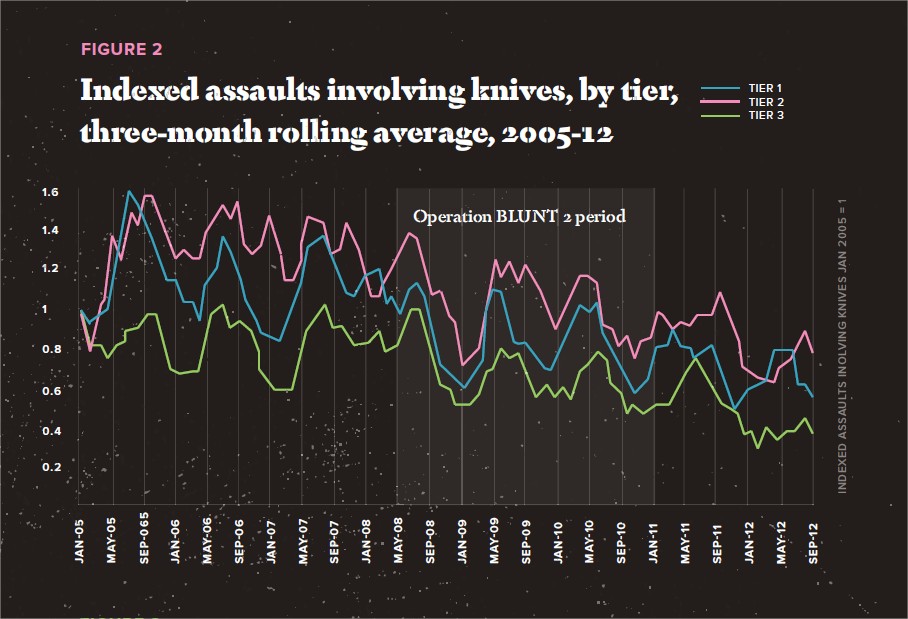

However, the tier system employed by the Met allows us to look more closely at the “effectiveness” of Operation Blunt 2 by comparing different areas. While it is true that gun and knife crime across London decreased by 11 percent, violent crime fell across every tier, including in those areas with minor or no increase in Section 60 stop and searches. An analysis of the operation in its entirety, carried out by the HMRC, found that:

However, the tier system employed by the Met allows us to look more closely at the “effectiveness” of Operation Blunt 2 by comparing different areas. While it is true that gun and knife crime across London decreased by 11 percent, violent crime fell across every tier, including in those areas with minor or no increase in Section 60 stop and searches. An analysis of the operation in its entirety, carried out by the HMRC, found that:

A conditional difference-in-difference regression analysis found no statistically significant crime-reduction effect across 11 offence types from the increase in weapons searches, when comparing boroughs with the biggest increases in stop and search activity with those that had much smaller increases (see Figure 2).

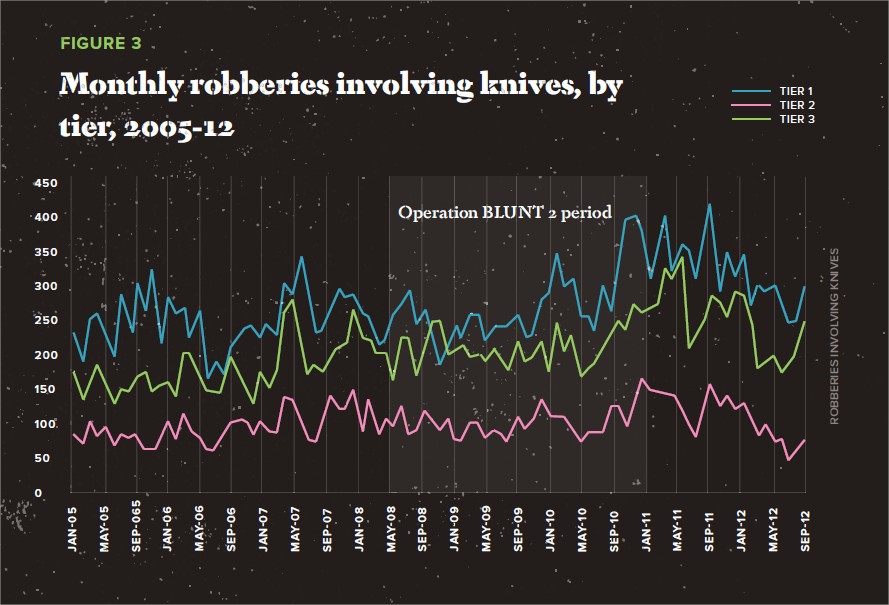

In fact, there appears to be a small increase in robberies involving knives over the three-year period in which Operation Blunt 2 was active as shown in Figure 3. This is of course not to say that Section 60 stop and searches lead to an increase in violent crime, but what we can certainly say is that these police powers have no positive effect on robberies involving knives. Yet there is another vital point to be made about Operation Blunt 2. It took place in the three years leading up to the civil unrest of August 2011, winding down just three months before the unrest. While the killing of Mark Duggan sparked an initial revolt, interviews with those implicated in the unrest cited police harassment as a key impetus in participating in the revolts that spread across England for four days. So Operation Blunt 2 should be understood as a precursor to the violence of 2011, just as the “sus” laws of 1981 led to the uprisings of that year.

In fact, there appears to be a small increase in robberies involving knives over the three-year period in which Operation Blunt 2 was active as shown in Figure 3. This is of course not to say that Section 60 stop and searches lead to an increase in violent crime, but what we can certainly say is that these police powers have no positive effect on robberies involving knives. Yet there is another vital point to be made about Operation Blunt 2. It took place in the three years leading up to the civil unrest of August 2011, winding down just three months before the unrest. While the killing of Mark Duggan sparked an initial revolt, interviews with those implicated in the unrest cited police harassment as a key impetus in participating in the revolts that spread across England for four days. So Operation Blunt 2 should be understood as a precursor to the violence of 2011, just as the “sus” laws of 1981 led to the uprisings of that year.

The Urgency of Transnational Resistance

While the fallout from Brexit and the election of Trump has seen a resurgence in the nasty racism that many thought had been left behind after the 1970s, with hate crimes on our streets, slurs in the press and immigration dominating political debate, it is vital that we do not lose sight of the newer, more subtle, neoliberal racisms that have been with us ever since the 1980s — on both sides of the Atlantic. Luckily, however, it is not only new articulations of racism that have made transatlantic connections: expressions of anti-racist resistance in the United States are also gaining currency in Britain today. The slogan “Black Lives Matter” has been echoed across anti-police violence marches, black justice campaigns and the multiple BLM chapters that have sprung up across Britain.

This network of activist collectives seeks to escalate existing actions, from community police monitoring projects, court actions and marches, to viral videos, subvertizing and direct action. In 2014, 76 people were arrested following a direct action that shut down London’s biggest shopping centre a few weeks before Christmas. Following migrant solidarity actions across three cities in 2016, disrupting spaces of transit, a number of activists faced arrest, charges and possible imprisonment. These direct actions do not simply challenge the racial violence reproduced by neoliberalism, but also disrupt the logistical circuits of distribution and spaces of consumption upon which its economic power relies. By disrupting these flows of capital, groups like Black Lives Matter counter both the multiple avenues of power deployed by neoliberalism and the new wave of anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim nationalist racism that has marked the latter part of 2016.

Direct actions do not simply challenge the racial violence reproduced by neoliberalism, but also disrupt the logistical circuits of distribution and spaces of consumption upon which its economic power relies.

While there are many differences between the forms of racism in the United States and Britain, there are also consistent parallels between the old center of empire and its most successful settler colony. As a political moment defined by Brexit and Trump compounds the neoliberal racial violence already underpinning these two nations, coordinated resistance has never been more urgent.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/neoliberalism-dog-whistle-racism/

Next Magazine article

Mass Surveillance and “Smart Totalitarianism”

- Chris Spannos

- December 18, 2016

The New Merchants of Death

- Jeremy Kuzmarov

- December 18, 2016