arindambanerjee / Shutterstock.com

Grounding the currents of Indigenous resistance

- January 16, 2018

Land & Liberation

Those joining the centuries-old Indigenous resistance in the Americas should discard Eurocentric narratives, epistemic violence and salvation narratives.

- Authors

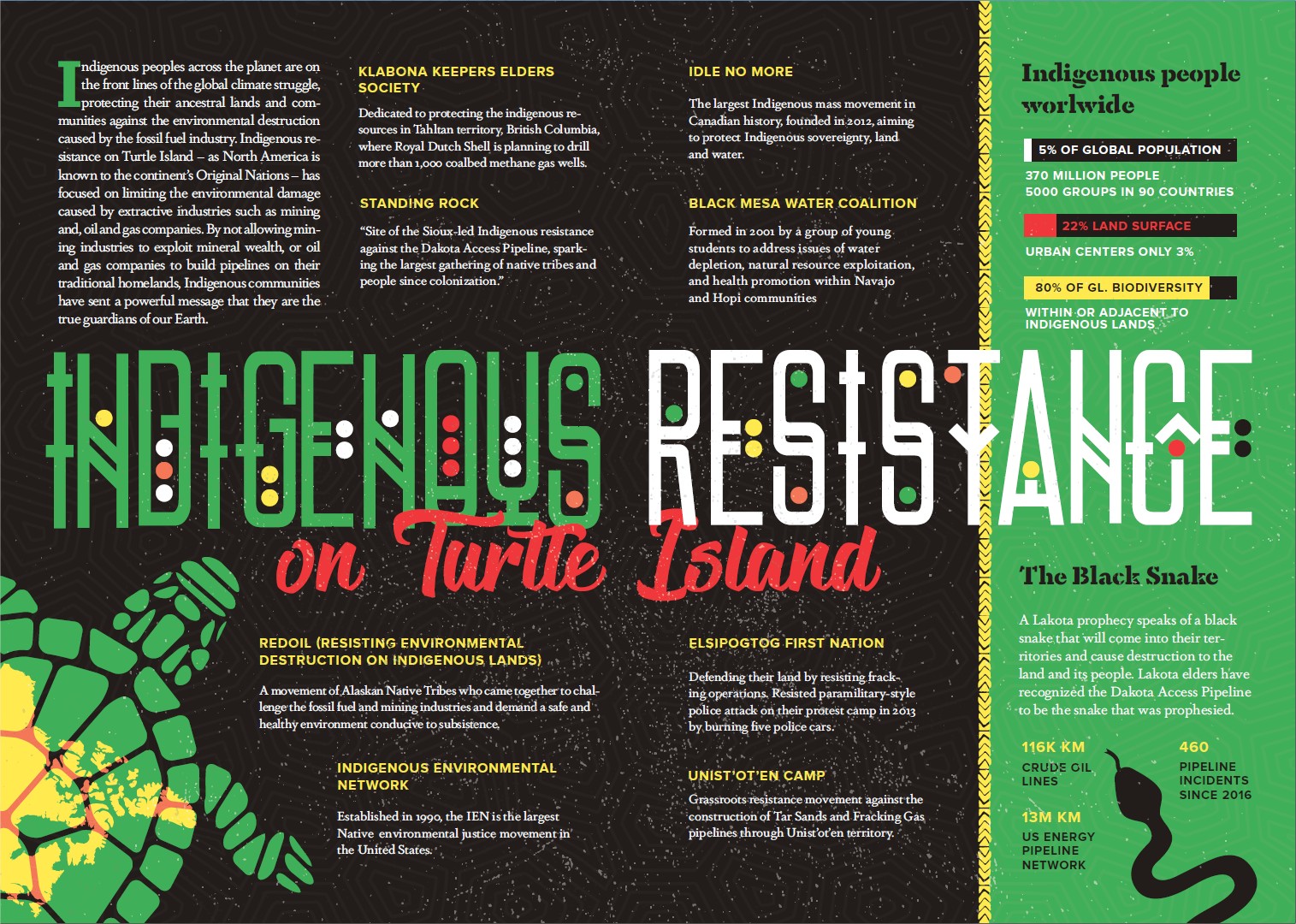

Indigenous peoples across the Americas have been rising up for 500 years, presenting multivalent forms of resistance to colonial violence, femicide, epistemicide and ecocide. The many faces and instances of this resistance do not register within leftist discourse and practice, and, in fact, are often invisibilized. As Indigenous women who have actively participated in and led community resistance to colonial violence, our response to the question “Why don’t the poor rise up?” is to share our own stories and the stories of our people here not as the answer to this question but as the context for our own question: “When will the left listen?”

This article was written at the onset of the fourth anniversary of the Idle No More movement and in the eighth month of the Indigenous-led action and encampment to stop construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on sacred ancestral lands of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation. We write from our respective cosmological and geographical locations. Praba Pilar, a Colombian Mestiza woman, now lives at the juncture of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Alex Wilson, who is Inniniwak, lives on the Saskatchewan River Delta in the traditional territory of her people, the Opaskwayak Cree Nation.

Indigenous resistance to colonization is the enduring history and present of the Americas, and the authors are connected as participants and organizers in Idle No More, a movement that draws together and organizes activists from throughout the Americas and beyond to honor Indigenous sovereignty and to protect the land and water. A considerable physical distance separates us, but the waterways along which we live flow into Lake Winnipeg, connecting us to one of the largest watersheds in the world, reaching west to Alberta, north to the Hudson Bay, east to the Great Lakes region and south well into the United States.

The complex structure and interactions within this river, lake and wetlands system offer a framework for our understanding of social movements. In our communities, Indigenous peoples’ cosmologies, lifeways and resistance focus on stewardship of the waters, lands, plants, animals and other life-forms that sustain us, and are guided by and govern ourselves based on traditional ethics that value relational accountability, reciprocity and collective and individual sovereignty. Navigating these interweaving ethical pathways have enabled our survival, as peoples, and now position us to reimagine a pluriverse that approaches the Zapatista’s concept of a “world in which many worlds coexist.”

Decolonizing the White Left

The question of why the poor do (not) rise up connects conceptually to the left. The American political philosopher Susan Buck-Morss reminds us that the contemporary left had its origin in European cosmology: “[T]he term ‘left’ is clearly a Western category, emerging in the context of the French Revolution.” The Argentinian scholar of modernity and coloniality Walter Mignolo acknowledges that the left has followed multiple trajectories and presented itself in multiple iterations (secular, theological, Marxist, European-influenced) around the globe but asserts that it can still most rightly be described as the “white left.” Mignolo’s naming of “the white left” is driven by the recognition that this movement emerged from a modernity that profits from and is dependent on coloniality.

This white left concerns us. Too often, its theorizing and work have universalized political categories that rely on and reflect exclusively European cosmologies, knowledges and theorists. Many, it seems, have forgotten the source of the languages, practices and legacies of the white left. Mignolo, however, has not: “Kant’s cosmopolitanism and its legacy propose the universalization of Western nativism/localism. And the Marxist left, for better or worse, belongs to that world.”

We acknowledge that there have been intersections (some of them meaningful and powerful) between the white left and Indigenous resistance in the Americas. Our question is broader. We question the axes of capitalism vs. socialism/communism, which cast Indigenous people as stand-ins for the proletariat or lumpenproletariat of capitalist Europe. Other non-white leftists have made similar challenges: “From Indian decolonial perspectives, the problem is not capitalism only, but also Occidentalism. Marx … proposed a class struggle within Occidental civilization, including the left, which originated in the West.”

We earlier described an ethical system that values relational accountability, reciprocity and collective and individual sovereignty for Indigenous peoples. These ethics, which existed well before the arrival of the earliest European explorers and settlers on our lands, have persisted and enabled us to maintain our resistance to colonial violence, ecocide and epistemicide. The interrelationships between our ethics, cosmologies, lifeways and the waters, lands and life-forms that sustain us are as complex and critical to our survival as those between the rivers, lakes and wetlands within the watershed where we reside. In our current political landscape, however, we must also navigate dangerously confining constructs introduced by European colonizers that function as ideological canals, locks and dams.

An early example of these confining constructs was the “Inter Caetera,” a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI in 1493 that laid out the justification for the Doctrine of Discovery. It established that Christian nations had a divine right (based on the Bible) to grant themselves legal ownerships of any “unoccupied” lands (where unoccupied was defined as the absence of Christian people) and dominion over any peoples on those lands.

A current example of these confining constructs is the salvation narrative unconsciously reproduced by many on the white left when they approach Indigenous or other non-European communities as allies but present solutions that have been developed in isolation, are paternalistic and/or are inappropriate to the context. Salvation narratives are often seen as benign, but they are not. They reflect and perpetuate the early justification for colonization, as described by Robert J. Miller in his book Native America, Discovered and Conquered, that “God had directed [Europeans] to bring civilized ways and education and religion to Indigenous peoples and to exercise paternalism and guardianship powers over them.”

Some on the white left rely on codified models of hierarchical leadership, structured authority and strategies and tactics, a construct that eradicates possibilities of deep alliance with many Indigenous people and groups who, for example, base their models on relationality or valorize community leadership rather than leadership vested in singular, celebrated figures. As Mignolo has observed, “Western Marxists belong to the same history of languages and memories as Christians, liberals and neoliberals. Marxism … is an outgrowth of Western civilization.”

For many on the white left, it can be difficult to recognize this. The ideological constructs introduced by the European colonizers have been here long enough that they may be mistaken for natural features of the political landscape. As Indigenous women engaged in resistance, we ask those on the white left to look more carefully, to acknowledge that colonization continues today, to make a choice to de-center the epistemic violence that accompanies it, and re-center themselves in decolonizing practices.

Hemispheric Connections

In the Southern Hemisphere of the Americas, co-author Praba comes from the largest highland plateau ecosystem in the world, the Páramo de Sumapaz of the Altiplano Cundinamarca in Colombia. Descended from the Muisca Chibcha of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Cordillera Oriental of the Andes, she was forced to leave Colombia as part of a diaspora fleeing the horrors of the hemisphere’s longest continuous internal war. Canada is the tenth country in which she has lived. Colombia has one of the highest rates of emigration in the Americas, with roughly one of every ten citizens living outside of the country. An even greater proportion of the population (5.8 million people within the country’s total population of 48.9 million) have been internally displaced, and the majority of these are Indigenous and/or Afro-Colombian.

The Toemaida military base, founded in 1954, is located in the region of Colombia where Praba spent her early years. The United States has been involved in military action in Colombia since the mid-1800s, and American soldiers are a “permanent presence” at Tolemaida. As noted in the report “Contribution to the Understanding of the Armed Conflict in Colombia” (Contribución al Entendimiento del Conflicto Armado en Colombia), issued by the Historic Commission of the Conflict and its Victims (Comisión Histórica del Conflicto y sus Víctimas) in February of 2015:

United States governments of the last seven decades are directly responsible for the perpetuation of the armed conflict in Colombia, in terms of how they have promoted the counterinsurgency in all of its manifestations, stimulating and training the Armed Forces with their methods of torture and elimination of those who they consider “internal enemies” and blocking all non-military paths to solve the structural causes of the social and armed conflict.

The military at Tolemaida has continuously attacked the powerful Indigenous resistance in the region, and is now deliberately contaminating the water supply, dumping “battery packs, broken glass, and ceramics, slowly rotting camouflage patterned clothing and bedding, munitions boxes (labeled in English and produced in the United States), and electrical equipment of all sorts… the water is visibly toxic green in parts, orange in others, with an oily sheen, and chemical foam.”

The highest coastal mountain range in the world, La Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta lies in the north of Colombia. The source of 36 rivers, the mountains feature a range of climates and abundant biodiversity. Over thousands of years, the Kogi people, who have stewarded the lands and waters, and resisted and survived colonization with their practices, beliefs and cosmologies intact, have continuously occupied them. In 1990, the Kogi invited a British filmmaker, Alan Ereira, to work on a documentary entitled From the Heart of the World: The Elder Brothers’ Warning. The documentary recorded the devastating climactic and environmental impacts that petroleum and resource extraction industries have had on the lands and waters of the Kogi people.

Since then, the Kogi have “witnessed landslides, floods, deforestation, the drying up of lakes and rivers, the stripping bare of mountain tops, the dying of trees.” In response, the Kogi recently made a second film with Ereira entitled Aluna. In the film, they explain the complex relationship of water from the coastal areas and lagoons to glacial mountain peaks. “They want to show urgently that the damage caused by logging, mining, the building of power stations, roads and the construction of ports along the coast and at the mouths of rivers … affects what happens at the top of the mountain. Once white-capped peaks are now brown and bare, lakes are parched and the trees and vegetation vital to them are withering.” What do the Kogi ask for in the film? They ask for non-Indigenous people to engage with Indigenous peoples and knowledge, to protect the waterways, lands and living creatures, and to halt ecocide.

Indigenous Peoples in the Cross Hairs

Not far from the Kogi territory lays the Northeast desert terrain, home to the Wayúu, the largest Indigenous population in Colombia. Having survived paramilitary massacres and displacement, they are now starving and dying because their water supply has been dammed, privatized and diverted to the El Cerrejon coal mine owned by Angloamerican, Glencore, and BHP Billiton. As reported by the mine’s Director of International Relations, the mine “uses 7.1 million gallons of water a day in its 24-hour operations.” The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs reports that the diversion of water, coupled with the current drought in the region, has left 37,000 Indigenous children in La Guajira malnourished and at least 5,000 dead of starvation. Armando Valbuena, the Wayúu traditional authority, identifies the actual number of deaths as “closer to 14,000, with no end in sight.”

The imposed national state borders of Venezuela and Colombia cross the territory of the Wayúu people. Both countries grossly violate Wayúu human rights. As Jakelyn Epieyu, of the Fuerza de Mujeres Wayúu relates, “I believe we live in a dictatorship of the left in Venezuela and in Colombia the dictatorship of the right, which has cost us blood and fire.” In Colombia, Indigenous and Afro-Colombians have been categorized as “a potential enemy to the identity of the nation. During the period when socio-biology and eugenics were popular ideologies of the ruling class and intellectuals of Latin America, Colombia defined the cultural base of the nation as ‘white.’”

This politics of blanqueamiento (becoming white) has persisted and affects every political arena in Colombia. As Misake community leader Segundo Tombé Morales relates, “[T]he indigenous movement, as understood in a general sense, remains on the floor, remains as if we were enemies of the Colombian people, of peasants, even any person today who sees an Indigenous person on the street, is enough motive for rejection and contempt.”

These are not abstractions or polemical discussions. These are lived experiences generated by an excruciating war with Indigenous people in the cross hairs, as explained by Alison Brysk in her book From Tribal Village to Global Village: “Indians are killed for defending their lands and for begging when displaced, for growing coca and for failing to grow coca, for supporting guerrillas and for failing to support guerrillas, and most of all, for daring to claim the rights Colombia grants but cannot provide.” The casualties include Praba’s family members, some of whom were killed in the war, and others who came close to dying but somehow survived: her mother, who was picked up off the street by a military tank (leading the family to flee the country), or Praba herself, who, when visiting Colombia in 2006, traveled down a road just 15 minutes before bombs detonated, killing everyone along a 1.5 kilometer stretch.

There are over 100 Indigenous groups in Colombia. In a 2009 ruling of the Constitutional Court of Columbia, more than a third of them were identified as “at risk of extermination by the armed conflict and forced displacement.” Indigenous communities in Colombia are disproportionately affected by the country’s internal war: “The parties to the conflict — namely, the Colombian armed forces, ultra-right paramilitary groups, and leftist guerrillas (such as the FARC and ELN) — have all been involved in crimes against Indigenous peoples.” Paramilitaries and armed government forces have committed massacres, assassinations and terrorized populations, engendering displacement. Leftist guerrillas have also played a destructive role, as explained by one of the justices who helped author the Court’s decision:

First, Indigenous-owned territory often serves as the “ideal,” remote place to conduct military operations. Second, parties to the conflict often incorporate Indigenous peoples into the violence through, amongst other things, recruitment, selective murders and use of communities as human shields. Third, resource-rich ancestral lands are threatened by the extractive economic activities related to the conflict, including mining, oil, timber and agribusiness. And fourth, the conflict worsens the pre-existing poverty, ill-health, malnutrition and other socio-economic disadvantages suffered by Indigenous peoples.

Misak leader Pedro Antonio Calambas Cuchillo explains that Indigenous people have little choice about their involvement: “We as Indigenous people have always tried to be separate from the armed groups, both the army and the guerrilla, but often conflicts happen between them, and we are always involved by the guerrillas, specifically the FARC, and by the public force.”

Colombia and other nations in the Southern Hemisphere, and Canada in the Northern Hemisphere, are connected through Canadian mining corporations. On a 2014 trip to Ottawa, sponsored in part by the Assembly of First Nations (a national organization that represents First Nations throughout Canada), Colombian human and Indigenous rights advocates observed that “in their country, Canadian trade and investment is profiting from a ‘genocide’ against Indigenous communities as land is cleared for resource development.” Indigenous peoples in Canada have told the same story.

Defending Land and Water

In the North, Alex emerges from Opaskwayak Cree Nation and the Saskatchewan River Delta. The name Saskatchewan comes from a Cree word, kisiskâciwanisîpiy, meaning “swift-flowing river.” The Saskatchewan River Delta is a 10,000 square kilometer system of rivers, lakes, wetlands and wildlife that acts as a filter, cleaning the water, lands and air in the region. As one of the most biodiverse areas of Canada, it has supported and sustained Indigenous communities for more than 10,000 years through hunting, trapping and fishing.

Traditional Cree knowledge traces their presence on these lands and waters back to both the last ice age and the one that preceded that. Today, the Saskatchewan River Delta is controlled and influenced by several human impacts. These include: the Manitoba Hydro dam in Grand Rapids; the EB Campbell Dam owned by SaskPower; Ducks Unlimited, a private American corporation; and phosphates from farm fertilizers and other contaminants that flow into the delta waterways.

The Cree people of this region have been defending land and waterways in the territory for many generations. Growing up in the north, Alex gathered her first knowledge about water by playing in it, testing the depths of the melt waters in spring by wading in until her boots filled, navigating the ephemeral creeks on homemade rafts in the summer, and creeping carefully out onto the ice following the first winter freeze to see if it was solid enough for skating. As she got older, her understanding of the water increased in complexity. In the Cree language of Alex’s people, the word for water is nipiy. The first syllable in this word, ni, refers to “life” and is also part of the Cree word for me or myself, drawing out the relationships between people and water. The term nipiy also has an alternate meaning: to die or bring death. Water, they understood, is a life or death matter.

The complex system of rivers and lakes in the north that sustained Indigenous people also provided the route for European colonization of their lands. The first significant European presence in the Canadian north were fur traders, who reached that territory by traveling the waterways that Indigenous people lived along. Indigenous people had relied on trapping for survival, harvesting critical resources that fed and clothed their families. They knew where animals in their territories could be found and how to harvest them in ways that would ensure their maintained presence, carefully managing their resources to ensure the sustainability of their way of life, their lands, and waters and the animals and plants who shared their territory.

The fur trade, however, generated profound changes in Indigenous people’s way of life, including a shift from sustainable stewardship of resources to a commodity-based economy and the decimation of critical animal populations. The fur trade also opened the north to missionaries, who brought salvation narratives and a determination to replace our traditional cosmologies, spirituality, lifeways and ethics with Christian constructs and practices.

The fur trade was the first of many damaging resource extraction activities in northern Canada, and the economy of that region now relies primarily on mining, forestry and hydroelectric generation. The Saskatchewan River Delta was altered dramatically by the construction of two large hydroelectric dams in the 1960s. The dams constrict and manipulate the flow of water along the Saskatchewan River, displacing the natural cycles that renew the surrounding lands and sustain wildlife, and generating flooding that has displaced entire Indigenous communities from their lands. Water from the river system is also used for agriculture and as drinking water for the cities and towns that have developed along the waterways. At the same time, agricultural drainage and wastewater from urban centers have introduced fertilizers and other agricultural and industrial chemicals, waste materials and other contaminants into the river system.

In Alex’s homeland of Northern Manitoba, either Manitoba Hydro or Ducks Unlimited now controls the waterways that Indigenous people stewarded for millennia. Alex’s family’s traditional trapline was along the Summerberry Marsh, between Moose Lake and Opaskwayak Cree Nation. Following construction of the dams, their devastating effects were evident throughout the lands and waters they trapped, hunted and harvested in. Settlements and gravesites were flooded. Rivers and lands they had traveled for years became unfamiliar and dangerous. Their connections to and relationships with the land, waters, furbearing animals, migratory birds and plants were disrupted, and it was impossible to maintain traditional ways of life. Trapping quotas (including one that set limits that decreased annually on the number of muskrats her grandfather could harvest) and fishing licenses were introduced, and traditional practices such as controlled burns (a technology to renew the muskrat population in a region) were banned. For Indigenous people, this forced a shift from food sovereignty to food dependency. People were forever changed.

Idle No More

The Indigenous grassroots movement Idle No More emerged in the fall of 2012 as a contemporary iteration of ongoing resistance to colonial violence directed at Indigenous people and the waterways, lands and living things that sustain them. It was started by four women (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) who felt compelled to take action to affirm Indigenous sovereignty, to protect and care for the land, water, each other and all living creatures, and to address old and new colonial forms of oppression.

The movement began not long after (then) Prime Minister Harper’s assertion at the 2009 G20 summit that Canada has “no history of colonization.” At the time Idle No More was emerging, an estimated 1,000 Indigenous women and girls from across Canada had either gone missing or been murdered, a number the federal government has since acknowledged is much too low, and may be as many as 4,000 women or girls. Idle No More’s emergence also closely followed the federal government introduction of legislation and legislative changes (now passed) that enabled governments and corporations to sidestep responsibilities and obligations that follow from or align with constitutionally and/or legally protected Indigenous rights, treaty-based rights and human rights. These included two omnibus bills with provisions that established procedures that would enable privatization of First Nations lands, replaced the existing Environmental Assessment Act and excepted pipelines and power lines from the Navigable Waters Protection Act, and removed thousands of lakes, rivers, and streams from protection under that same act.

Idle No More began as a series of teach-ins in Saskatchewan on the planned legislative changes, round dances that brought together Indigenous people and our allies in public spaces such as government buildings, malls, or intersections, and, in its first month, a National Day of Action and Solidarity on which rallies and marches to protest the impending legislation were held in cities throughout Canada, drawing anywhere from hundreds to thousands of people to each event. By transforming public spaces into political spaces, it was no longer possible for us to be invisibilized. Those around us could no longer wilfully not see Indigenous people and the issues they were addressing.

Idle No More quickly grew into a global movement focused on Indigenous peoples’ right to sovereignty, our responsibility to protect our people, lands, waterways and other living things from corporate and colonial violence and destruction, and ongoing resistance to neo-colonialism and neoliberalism. These issues lay out a large expanse of common ground and a notable feature of Idle No More has been the extent to which it has worked in solidarity with like-minded organizations and individual allies. Idle No More also operates within a non-hierarchic leadership model that is based on the traditional ethic of relational responsibility. It has reached out (both digitally and physically) to bring people into the circle, to step into leadership by becoming political actors. As Wanda Nanibush, an Idle No More organizer, has observed:

We as Idle No More have put forward the voices of women, the voices of two-spirited people and the voices of youth. This has really galvanized voices that haven’t been part of this thinking or a part of democracy in Canada. Idle No More has been really amazing at raising the question of democracy and how we’re going to run this country, and whose voices are really going to be at the table, to the forefront of all of our struggles… all the struggles do come together under Indigenous rights.

Joining the indigenous resistance

The Kogi, the Wayúu and Idle No More are connected across the Americas through the violence of colonization, through bodies — of land, water, ecosystems, living beings, animals and humans — and through knowledges, ways of being, cosmovisions and resistance. Those who want to join the 500 years of Indigenous resistance can work to release the locks they impose on alliance, by releasing universalized Eurocentric narratives and cosmovision, epistemic violence and salvation narratives.

When Subcomandante Marcos joined with Mayans, he had to rethink his urban Marxist perspective on Indigenous terms. He writes about the experience: “The end result was that we were not talking to an indigenous movement waiting for a savior but with an indigenous movement with a long tradition of struggle, with significant experience, and very intelligent: a movement that was using us as its armed men.”

This essay is a book chapter excerpt from Why Don’t the Poor Rise Up? (AK Press, 2017). All translations of quotations from Spanish by Praba Pilar.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/indigenous-peoples-resistance-americas/