Dismantling neoliberal education: a lesson from the Zapatistas

- April 4, 2016

Education & Emancipation

The non-hierarchical education of the Zapatistas cries dignity and suggests that the suffering of the neoliberal university can be withstood and overcome.

- Author

I’ve said it before—in contrast to those traditional stories that begin with ‘Once upon a time…’ Zapatista stories begin with ‘There will be a time…’

— Subcomandante Galeano (formerly Marcos)

The story of the Zapatistas is one of dignity, outrage, and grit. It is an enduring saga of over 500 years of resistance to the attempted conquest of the land and lives of indigenous peasants. It is nothing less than a revolutionary and poetic account of hope, insurgency and liberation—a movement characterized as much by adversity and anguish, as it is by laughter and dancing.

More precisely, the ongoing chronicles of the Zapatista insurrection provide a dramatic account of how indigenous people have defied the imposition of state violence, oppressive gender roles and capitalist plunder. And for people of the Ch’ol, Tseltal, Tsotsil, Tojolabal, Mam and Zoque communities in Chiapas, Mexico who make the decision to become Zapatista, it is a story reborn, revitalized and re-learned each new day, with each new step.

It is with this context in mind that I provide a brief overview of how the Zapatistas’ vibrant construction of resistance offers hope to those of us struggling within-and-against the neoliberal university.

For Sts’ikel Vokol and Casting Out

Power was trying to teach us individualism and profit…We were not good students.

— Compañera Ana Maria

Zapatista Education Promoter

Before we dive too deeply into things, I have a confession to make. I have absolutely no faith whatsoever that the academic status quo will ever be reformed. Audre Lorde tells us that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” while Emma Goldman notes that “the most violent element in society is ignorance.” Most universities, after all, were assembled using an ignorant master’s racist and patriarchal logic. That is, the academy was broken to begin with, and remains that way.

Hence, when it comes to the existence of any entity or institution that emerges from the colonizer’s mindset, like neoliberal education, I agree with Frantz Fanon, who states that “we must shake off the heavy darkness in which we were plunged, and leave it behind.”

Hence, when it comes to the existence of any entity or institution that emerges from the colonizer’s mindset, like neoliberal education, I agree with Frantz Fanon, who states that “we must shake off the heavy darkness in which we were plunged, and leave it behind.”

In short, neoliberalism, the world’s current “heavy darkness”, must be cast out, and the universities in which it is being taught must be pummeled into ruin. And despite the fact that such a comment may seemingly be replete with cynicism and despair, it is actually deeply rooted in yearning and hope — for resistance.

When speaking of “resistance” one must tread lightly because it is, indeed, an intensely contested term. Resistance can mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people. For this piece then, I draw from (what I feel is) perhaps the most fertile and most evolved source of resistance that exists — the Zapatista insurgency.

The analysis that follows is thus informed by the Tsotsil (indigenous Maya) concept of sts’ikel vokol, which means “withstanding suffering.” And when resistance is defined in this manner possibilities blossom. Possibilities that resistance can mean empathy and emotional labor, as well as compassion and mutual aid, regardless of one’s calendar and geography… or even university.

“Death by a Thousand Cuts”

The basis of neoliberalism is a contradiction: in order to maintain itself, it must devour itself, and therefore, destroy itself.

— Don Durito de la Lacandona

Beetle, Knight Errant

Neoliberalism is a force to be reckoned with. Globally, it is exacerbating dependency, debt and environmental destruction on a widespread scale through the proliferation of free trade policies, which slash the rights and protections of workers, environments and societies alike.

On a personal level, it convinces people that individualism, competition and self-commodification are the natural conditions of life. Consequently, civil society is compelled to accept, through manipulative capitalist rhetoric, that the world is nothing more than a market in which everything, and everyone, can be bought and sold. The misery of others, then, is deemed to be merely collateral damage of an inherently bleak and fragmented world. Chillingly, higher education is not immune to such malevolent tendencies.

The debilitating effects that neoliberalism has on higher education have been written about at length. The pathological obsession on generating income that university administrators (and even some faculty members) give precedent to (in lieu of encouraging critical thought, self-reflection and praxis) is also well documented.

The debilitating effects that neoliberalism has on higher education have been written about at length. The pathological obsession on generating income that university administrators (and even some faculty members) give precedent to (in lieu of encouraging critical thought, self-reflection and praxis) is also well documented.

Less attention, however, has been paid to the psychological injuries inflicted upon people by the disciplinary mechanisms of the neoliberal university, like scholarly rankings, impact factors, citation metrics, achievement audits, publication quotas, pressure to win prestigious grants, award cultures, getting “lines on the CV”, and so on.

If one listens to colleagues or friends working in the academy, it will not take long to hear stories of acute anxiety, depression and paranoia, as well as feelings of despair, non-belonging and hopelessness. Life in the neoliberal university has thereby become a proverbial “death by a thousand cuts” — just ask any mother working within it.

One of the most disconcerting, and overlooked, products of neoliberal higher education is how students are treated by it. “Learning” now consists of rote memorization, standardized tests, high-stakes exams, factory-like classroom settings, hierarchical competition amongst peers, the accumulation of massive debts to afford rising tuition costs, and patronizingly being scolded that “this is what you signed up for.”

Students must navigate this neoliberal gauntlet while also simultaneously being pressured into enthusiastically performing the grotesque bourgeois role of “entrepreneur” or “global citizen”. Paulo Freire said there would be dehumanizing days like this.

Without question, neoliberalism has launched a full-fledged assault on the mental health of faculty and students alike, not to mention the well-being of heavily-exploited, contracted, typically non-unionized workers in the food service and maintenance sectors of many universities. These nearly impossible circumstances are often the only choices many have in simply making a go of it in life. And a situation in which it is compulsory for people to discipline and punish themselves, as well as others, into becoming hyper-competitive, self-promoting functionaries of capitalism is — as a Zapatista education promoter so vividly put it — olvido: oblivion.

Decolonization, autonomy and the Spirit of Revolt

The battle for humanity and against neoliberalism was and is ours, and also that of many others from below. Against death — We demand life.

— Subcomandante Galeano

(formerly Marcos)

It should be pointed out that the ongoing project of Zapatista autonomy is the direct result of indigenous people’s self-determination, as well as their decision to engage in highly disciplined organizing against a neo-colonial elite. More pointedly, the Zapatistas sacrificed themselves to make the world a better and safer place.

Fittingly, one of the most widely seen phrases scattered across the rebel territories of Chiapas reads: Para Todos Todo, Para Nosotros Nada (“Everything for Everyone, Nothing for Us”). In the face of global capitalism, such a statement is as profound as it is humble. It explicitly foregrounds cooperation and selflessness; virtues the Zapatistas have integrated into their autonomous education system.

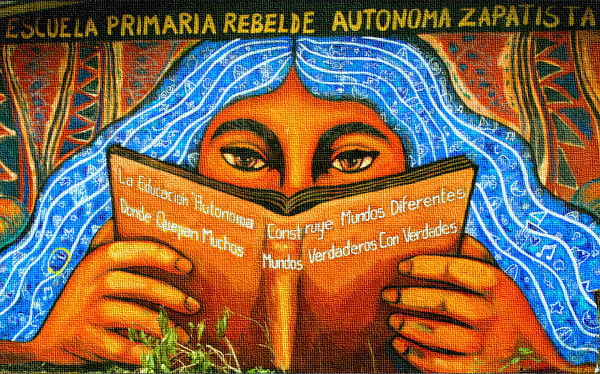

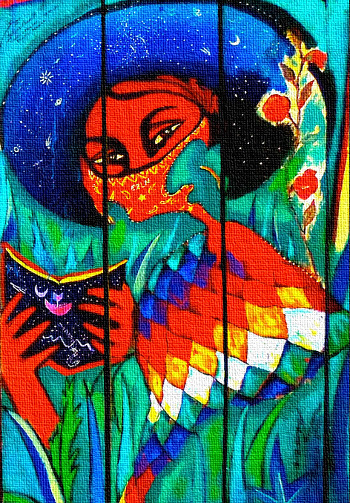

As indigenous rebels, the Zapatistas astutely refer to state-sanctioned schools and universities as “corrals of thought domestication.” This is due to the emphasis that government-legitimated institutions place on coercing students and faculty into becoming docile citizen-consumers. The Zapatista response to the prospect of having to send their children into such hostile learning environments was open and armed revolt.

Thus, on January 1, 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) rekindled the spirit of Emiliano Zapata’s revolutionary call for Tierra y Libertad (“Land and Freedom”), cried ¡Ya Basta! (Enough!), and “woke up history” by taking back the land they had been dispossessed of.

Given their foresight and actions, one cannot help but be reminded of anarcho-communist geographer Peter Kropotkin, who in 1880 stated: “There are periods in the life of human society when revolution becomes an imperative necessity, when it proclaims itself as inevitable.”

In successfully liberating themselves from belligerent edicts of the Mexican government (el mal gobierno, “the bad government”), the Zapatistas now practice education on their own terms. They are not beholden to the parochial oversight of managerialist bureaucracies like many of us in neoliberal universities are. On the contrary, Zapatista teaching philosophy comes “from below” and is anchored in land and indigenous custom. Their approach is best illustrated by the duelling axiom Preguntando Caminamos (“Asking, We Walk”), which sees Zapatista communities generate their “syllabi” through popular assembly, participatory democracy and communal decision-making.

In successfully liberating themselves from belligerent edicts of the Mexican government (el mal gobierno, “the bad government”), the Zapatistas now practice education on their own terms. They are not beholden to the parochial oversight of managerialist bureaucracies like many of us in neoliberal universities are. On the contrary, Zapatista teaching philosophy comes “from below” and is anchored in land and indigenous custom. Their approach is best illustrated by the duelling axiom Preguntando Caminamos (“Asking, We Walk”), which sees Zapatista communities generate their “syllabi” through popular assembly, participatory democracy and communal decision-making.

These horizontalist processes advance by focusing on the histories, ecologies and needs of their respective bases of support. Zapatista “classrooms” therefore include territorially-situated lessons on organic agroforestry, natural/herbal medicines, food sovereignty and regional indigenous languages. Given the geopolitical context of their movement, then, Zapatista teaching methods constitute acts of decolonization in and of themselves.

This leaves one wondering if the neoliberal academy might learn a thing or two from the Zapatistas in regard to endorsing both indigenous worldviews and place-based education as essential to any program of study. And even given the depth and breadth of the Zapatista’s “curricula,” the goal of their rogue pedagogy can be summed up as trying to instill one thing: a capacity for discernment, which they foster through Zapatismo.

Zapatismo as Liberation Geography

Liberation will not fall like a miracle from the sky; we must construct it ourselves. So let’s not wait, let us begin…

— Zapatista Pamphlet on Political Education

A kind and good-humored education promoter explained the notion of Zapatismo to me on a brisk and fog-blanketed weekday morning in the misty highlands of Chiapas. In describing it, they noted: “Zapatismo is neither a model, nor doctrine. It’s also not an ideology or blueprint, rather, it is the intuition one feels inside their chest to reflect the dignity of others, which mutually enlarges our hearts.”

Additionally, as loyal readers of ROAR’s Leonidas Oikonomakis will recognize, Zapatismo is also commonly comprised of seven principles:

-

Obedecer y no Mandar (to obey, not command)

-

Proponer y no Imponer (to propose, not impose)

-

Representar y no Suplantar (to represent, not supplant)

-

Convencer y no Vencer (to convince, not conquer)

-

Construir y no Destruir (to construct, not destroy)

-

Servir y no Servirse (to serve, not to serve oneself)

-

Bajar y no Subir (to go down, not up; to work from below, not seek to rise)

These convictions guide the everyday efforts of the Zapatistas in the building of what they refer to as Un Mundo Donde Quepan Muchos Mundos (“A World Where Many Worlds Fit”). Zapatismo, then, can also be thought of as the collective expression of a radical imagination, the manifestation of a shared creative vision, and a material liberation of geography.

What it gives rise to in terms of pedagogy are possibilities for establishing respectful methods of teaching and learning that champion the recognition (and practice) of mutuality, interdependency, introspection and dignity.

What it gives rise to in terms of pedagogy are possibilities for establishing respectful methods of teaching and learning that champion the recognition (and practice) of mutuality, interdependency, introspection and dignity.

These non-hierarchical/anti-neoliberal facets of Zapatista teaching are evident in the grassroots focus they take. Local knowledge is so central amongst their communities that many of the promotores de educación (education promoters) often come from, and remain in, the same autonomous municipalities as the students. There are no sessional contracts and teachers are not disposed of after only a few months on the job.

In the spirit of equality, Zapatistas maintain neither hierarchical distinction nor vertical rank amongst their “faculty members.” Everyone is simply, and humbly, an education promoter. This jettisoning of professional titles and institutionally-legitimated credentials highlights how the Zapatistas are able to thwart assertions of ego/hierarchical authority and abolish the competitive individualism that so often corrupts neoliberal universities. Fundamentally, they are unsettling the rigid boundaries dividing “those who know” from “those who do not know” — because there is nothing revolutionary about arrogance.

Even more radically, the Zapatistas incorporate gender justice (like Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law), food sovereignty, anti-systemic healthcare, and queer discourse (like using the inclusive terms otroas/otr@s, compañeroas/compañer@s, and so on, as well as “otherly” as a whimsical and respectful compliment) into their day-to-day learning.

Even more radically, the Zapatistas incorporate gender justice (like Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Law), food sovereignty, anti-systemic healthcare, and queer discourse (like using the inclusive terms otroas/otr@s, compañeroas/compañer@s, and so on, as well as “otherly” as a whimsical and respectful compliment) into their day-to-day learning.

They also do not distribute final marks to signify an end to the learning process, and no grades are used to compare or condemn students. In these ways, the Zapatistas underscore how education is neither a competition, nor something to be “completed”. These transgressive strategies have essentially aided the Zapatistas in eradicating shame from the learning process, which they deem necessary because of just how toxic, petty and vicious neoliberal education can become.

To conclude, the academic status quo is punishing — and must be abandoned. Neoliberalism has hijacked education and is holding it hostage. It demands ransom in the form of obedience, conformity and free labor, whilst also disciplining the curiosity, creativity and imagination out of students, faculty and workers. The neoliberal university itself is sterile, negligent and conformist; as well as suffocating, lonely and gray.

Collective resistance is exigent because we need a new burst of hope amidst such a “heavy darkness” — and Zapatismo nurtures hope. Not hope in an abstract sense of the word, but the type of hope that when sown through compassion and empathy, and nourished by shared rage, resonates and is felt.

Zapatismo gives rise to the kind of hope that comforts affliction, enlarges hearts and wakes up history. The kind of hope that causes chests to swell, jaws to clench and arms to lock when others are being humiliated or hurt — regardless of whether it be by individual, institution, system, or structure.

Zapatismo cries dignity and suggests the suffering of the neoliberal university can be withstood and overcome, because truth be told, neoliberalism is not an ominous, panoptic master — it is simply a reality. And realities can be changed — just ask a Zapatista.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/neoliberal-education-zapatista-pedagogy/