Between Light and Shadow: Marcos’ last words

- May 28, 2014

Anarchism & Autonomy

Here is the English translation of Subcomandante Marcos’ last public statement: “We think it is necessary for one of us to die so that Galeano lives.”

- Author

This communiqué was released by the EZLN General Command on May 25, 2014, and just translated into English for Enlace Zapatista. In these final words spoken during the commemoration of the murdered compañero Galeano at the Zapatista rebel community of La Realidad, Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation announces that he will henceforth cease to exist. For background, check out this piece by Leonidas Oikonomakis. All photos were taken at La Realidad, and are courtesy of our compañer@s from Cooperativa de Medios and the autonomous media of Chiapas.

BETWEEN LIGHT AND SHADOW

In La Realidad [Reality], Planet Earth

May 2014

Compañera, compañeroa, compañero:

Good evening, afternoon, or morning, whichever it may be in your geography, time, and way of being.

Good very early morning.

I would like to ask the compañeras, compañ eros and compañeroas of the Sixth who came from other places, especially the compañeros from the independent media, for your patience, tolerance, and understanding for what I am about to say, because these will be the final words that I speak in public before I cease to exist.

eros and compañeroas of the Sixth who came from other places, especially the compañeros from the independent media, for your patience, tolerance, and understanding for what I am about to say, because these will be the final words that I speak in public before I cease to exist.

I am speaking to you and to those who listen to and look at us through you.

Perhaps at the start, or as these words unfold, the sensation will grow in your heart that something is out of place, that something doesn’t quite fit, as if you were missing one or various pieces that would help make sense of the puzzle that is about to be revealed to you. As if indeed what is missing is still pending.

Maybe later — days, weeks, months, years or decades later — what we are about to say will be understood.

My compañeras and compañeros at all levels of the EZLN do not worry me, because this is indeed our way here: to walk and to struggle, always knowing that what is missing is yet to come.

What’s more, and without meaning to offend anyone, the intelligence of the Zapatista compas is way above average.

In addition, it pleases and fills us with pride that this collective decision will be made known in front of compañeras, compañeros and compañeroas, both of the EZLN and of the Sixth.

And how wonderful that it will be through the free, alternative, and independent media that this archipelago of pain, rage, and dignified struggle — what we call “the Sixth” — will hear what I am about to say, wherever they may be.

If anyone else is interested in knowing what happened today, they will have to go to the independent media to find out.

So, here we go. Welcome to the Zapatista reality (La Realidad).

I. A difficult decision.

When we erupted and interrupted in 1994 with blood and fire, it was not the beginning of war for us as Zapatistas.

The war from above, with its death and destruction, its dispossession and humiliation, its exploitation and the silence it imposed on the defeated, we had been enduring for centuries.

What began for us in 1994 is one of many moments of war by those below against those above, against their world.

This war of resistance is fought day-in and day-out in the streets of any corner of the five continents, in their countrysides and in their mountains.

It was and is ours, as it is of many from below, a war for humanity and against neoliberalism.

Against death, we demand life.

Against silence, we demand the word and respect.

Against oblivion, memory.

Against humiliation and contempt, dignity.

Against oppression, rebellion.

Against slavery, freedom.

Against imposition, democracy.

Against crime, justice.

Who with the least bit of humanity in their veins would or could question these demands?

And many listened to us then.

The war we waged gave us the privilege of arriving to attentive and generous ears and hearts in geographies near and far.

Even lacking what was then lacking, and as of yet missing what is yet to come, we managed to attain the other’s gaze, their ear, and their heart.

It was then that we saw the need to respond to a critical question.

“What next?”

In the gloomy calculations on the eve of war there hadn’t been any possibility of posing any question whatsoever. And so this question brought us to others:

Should we prepare those who come after us for the path of death?

Should we develop more and better soldiers?

Invest our efforts in improving our battered war machine?

Simulate dialogues and a disposition toward peace while preparing new attacks?

Kill or die as the only destiny?

Or should we reconstruct the path of life,  that which those from above had broken and continue breaking?

that which those from above had broken and continue breaking?

The path that belongs not only to indigenous people, but to workers, students, teachers, youth, peasants, along with all of those differences that are celebrated above and persecuted and punished below.

Should we have adorned with our blood the path that others have charted to Power, or should we have turned our heart and gaze toward who we are, toward those who are what we are — that is, the indigenous people, guardians of the earth and of memory?

Nobody listened then, but in the first babblings that were our words we made note that our dilemma was not between negotiating and fighting, but between dying and living.

Whoever noticed then that this early dilemma was not an individual one would have perhaps better understood what has occurred in the Zapatista reality over the last 20 years.

But I was telling you that we came across this question and this dilemma.

And we chose.

And rather than dedicating ourselves to training guerrillas, soldiers, and squadrons, we developed education and health promoters, who went about building the foundations of autonomy that today amaze the world.

Instead of constructing barracks, improving our weapons, and building walls and trenches, we built schools, hospitals and health centers; improving our living conditions.

Instead of fighting for a place in the Parthenon of individualized deaths of those from below, we chose to construct life.

All this in the midst of a war that was no less lethal because it was silent.

Because, compas, it is one thing to yell, “You Are Not Alone,” and another to face an armored column of federal troops with only one’s body, which is what happened in the Highlands Zone of Chiapas. And then if you are lucky someone finds out about it, and with a little more luck the person who finds out is outraged, and then with another bit of luck the outraged person does something about it.

In the meantime, the tanks are held back by Zapatista women, and in the absence of ammunition, insults and stones would force the serpent of steel to retreat.

And in the Northern Zone of Chiapas, to endure the birth and development of the guardias blancas [armed thugs traditionally hired by landowners] who would then be recycled as paramilitaries; and in the Tzotz Choj Zone, the continual aggression of peasant organizations who have no sign of being “independent” even in name; and in the Selva Tzeltal zone, the combination of the paramilitaries and contras [anti-Zapatistas].

It is one thing to say, “We Are All Marcos” or “We Are Not All Marcos,” depending on the situation, and quite another to endure persecution with all of the machinery of war: the invasion of communities, the “combing” of the mountains, the use of trained attack dogs, the whirling blades of armed helicopters destroying the crests of the ceiba trees, the “Wanted: Dead or Alive” that was born in the first days of January 1994 and reached its most hysterical level in 1995 and in the remaining years of the administration of that now-employee of a multinational corporation, which this Selva Fronteriza zone suffered as of 1995 and to which must be added the same sequence of aggressions from peasant organizations, the use of paramilitaries, militarization, and harassment.

If there exists a myth today in any of this, it is not the ski mask, but the lie that has been repeated from those days onward, and even taken up by highly educated people, that the war against the Zapatistas lasted only 12 days.

I will not provide a detailed retelling. Someone with a bit of critical spirit and seriousness can reconstruct the history, and add and subtract to reach the bottom line, and then say if there are and ever were more reporters than police and soldiers; if there was more flattery than threats and insults, if the price advertised was to see the ski mask or to capture him “dead or alive.”

Under these conditions, at times with only our own strength and at other times with the generous and unconditional support of good people across the world, we moved forward in the construction — still incomplete, true, but nevertheless defined — of what we are.

So it isn’t just an expression, a fortunate or unfortunate one depending on whether you see from above or from below, to say, “Here we are, the dead of always, dying again, but this time in order to live.” It is reality.

And almost 20 years later…

On December 21, 2012, when the political and the esoteric coincided, as they have at other times in preaching catastrophes that are meant, as they always are, for those from below, we repeated the sleight of hand of January of ’94 and, without firing a single shot, without arms, with only our silence, we once again humbled the arrogant pride of the cities that are the cradle and hotbed of racism and contempt.

If on January 1, 1994, it was tho usands of faceless men and women who attacked and defeated the garrisons that protected the cities, on December 21, 2012, it was tens of thousands who took, without words, those buildings where they celebrated our disappearance.

usands of faceless men and women who attacked and defeated the garrisons that protected the cities, on December 21, 2012, it was tens of thousands who took, without words, those buildings where they celebrated our disappearance.

The mere indisputable fact that the EZLN had not only not been weakened, much less disappeared, but rather had grown quantitatively and qualitatively would have been enough for any moderately intelligent mind to understand that, in these 20 years, something had changed within the EZLN and the communities.

Perhaps more than a few people think that we made the wrong choice; that an army cannot and should not endeavor toward peace.

We made that choice for many reasons, it’s true, but the primary one was and is because this is the way that we [as an army] could ultimately disappear.

Maybe it’s true. Maybe we were wrong in choosing to cultivate life instead of worshipping death.

But we made the choice without listening to those on the outside. Without listening to those who always demand and insist on a fight to the death, as long as others will be the ones to do the dying.

We made the choice while looking and listening inward, as the collective Votán that w e are.

e are.

We chose rebellion, that is to say, life.

That is not to say that we didn’t know that the war from above would try and would keep trying to re-assert its domination over us.

We knew and we know that we would have to repeatedly defend what we are and how we are.

We knew and we know that there will continue to be death in order for there to be life.

We knew and we know that in order to live, we die.

II. A failure?

They say out there that we haven’t achieved anything for ourselves.

It never ceases to surprise us that they hold on to this position with such self-assurance.

They think that the sons and daughters of the comandantes and comandantas should be enjoying trips abroad, studying in private schools, and achieving high posts in business or political realms. That instead of working the land and producing their food with sweat and determination, they should shine in social networks, amuse themselves in clubs, show off in luxury.

Maybe the subcomandantes should procreate and pass their jobs, perks, and stages onto their children, as politicians from across the spectrum do.

Maybe we should, like the leaders of the CIOAC-H and other peasant organizations do, receive privileges and payment in the form of projects and monetary resources, keeping the largest part for ourselves while leaving the bases [of support] with only a few crumbs, in exchange for following the criminal orders that come from above.

Well it’s true, we haven’t achieved any of this for ourselves.

While difficult to believe, 20 years after that “Nothing For Ourselves,” it didn’t turn out to be a slogan, a good phrase for posters and songs, but rather a reality, the reality.

If being accountable is what marks failure, then unaccountability is the path to success, the road to Power.

But that’s not where we want to go.

It doesn’t interest us.

Within these parameters, we prefer to fail than to succeed.

III. The handoff, or change.

In these 20 years, there has been a multiple and complex handoff, or change, within the EZLN.

Some have only noticed the obvious: the generational.

Today, those who were small or had not even been born at the beginning of the uprising are the ones carrying the struggle forward and directing the resistance.

But some of the experts have not considered other changes:

That of class: from the enlightened middle class to the indigenous peasant.

That of race: from mestizo leadership to a purely indigenous leadership.

That of race: from mestizo leadership to a purely indigenous leadership.

And the most important: the change in thinking: from revolutionary vanguardism to “governing by obeying;” from taking Power Above to the creation of power below; from professional politics to everyday politics; from the leaders to the people; from the marginalization of gender to the direct participation of women; from the mocking of the other to the celebration of difference.

I won’t expand more on this because the course “Freedom According to the Zapatistas” was precisely the opportunity to confirm whether in organized territory, the celebrity figure is valued over the community.

Personally, I don’t understand why thinking people who affirm that history is made by the people get so frightened in the face of an existing government of the people where “specialists” are nowhere to be seen.

Why does it terrify them so that the people command, that they are the ones who determine their own steps?

Why do they shake their heads with disapproval in the face of “rule by obeying?”

The cult of individualism finds in the cult of vanguardism its most fanatical extreme.

And it is this precisely — that the indigenous rule, and now with an indigenous person as the spokesperson and chief — that terrifies them, repels them, and finally sends them looking for someone requiring vanguards, bosses, and leaders. Because there is also racism on the left, above all among that left which claims to be revolutionary.

The ezetaelene is not of this kind. That’s why not just anybody can be a Zapatista.

IV. A changing and moldable hologram. That which will not be.

Before the dawn of 1994, I spent 10 years in these mountains. I met and personally interacted with some whose death we all died in part. Since then, I know and interact with others that are today here with us.

In many of the smallest hours of the morning I found myself trying to digest the stories that they told me, the worlds that they sketched with their silences, hands, and gazes, their insistence in pointing to something else, something further.

Was it a dream, that world so other, so distant, so foreign?

Sometimes I thought that they had gone ahead of us all, that the words that guided and guide us came from times that didn’t have a calendar, that were lost in imprecise geographies: always with the dignified south omnipresent in all the cardinal points.

Later I learned that they weren’t telling me about an inexact, and therefore, improbable world.

That world was already unfolding.

And you? Did you not see it? Do you not see it?

We have not deceived anyone from below. We have not hidden the fact that we are an army, with its pyramidal structure, its central command, it decisions hailing from above to below. We didn’t deny what we are in order to ingratiate ourselves with the libertarians or to move with the trends.

But anyone can see now whether ours is an army that supplants or imposes.

And I should say that I have already asked compañero Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés’ permission to say this:

Nothing that we’ve done, for better or for worse, would have been possible without an armed military, the Zapatista Army for National Liberation; without it we would not have risen up against the bad government exercising the right to legitimate violence. The violence of below in the face of the violence of above.

We are warriors and as such we know our role and our moment.

In the earliest hours of the morning on the first day of the first month of the year 1994, an army of giants, that is to say, of indigenous rebels, descended on the cities to shake the world with its step.

Only a few days later, with the blood of our fallen soldiers still fresh on the city streets, we noticed that those from outside did not see us.

Accustomed to looking down on the indigenous from above, they didn’t lift their gaze to look at us.

Accustomed to seeing us humiliated, their heart did not understand our dignified rebellion.

Their gaze had stopped on the only mestizo they saw with a ski mask, that is, they didn’t see.

Our authorities, our commanders, then said to us:

“They can only see those who are as small as they are. Let’s make someone as small as they are, so that they can see him and through him, they can see us.”

And so began a complex maneuver of distraction, a terrible and marvelous magic trick, a malicious move from the indigenous heart that we are, with indigenous wisdom challenging one of the bastions of modernity: the media.

And so began the construction of the character named “Marcos.”

I ask that you follow me in this reasoning:

Suppose that there is another way to neutralize a criminal. For example, creating their murder weapon, making them think that it is effective, enjoining them to build, on the basis of this effectiveness, their entire plan, so that in the moment that they prepare to shoot, the “weapon” goes back to being what it always was: an illusion.

The entire system, but above all its media, plays the game of creating celebrities who it later destroys if they don’t yield to its designs.

Its power resided (now no longer, as it has been displaced by social media) in deciding what and who existed in the moment when they decided what to name and what to silence.

But really, don’t pay much attention to me; as has been evident over these 20 years, I don’t know anything about the mass media.

The truth is that this SupMarcos went from being a spokesperson to being a distraction.

If the path to war, that is to say, the path to death, had taken us 10 years, the path to life required more time and more effort, not to mention more blood.

Because, though you may not believe it, it is easier to die than it is to live.

Because, though you may not believe it, it is easier to die than it is to live.

We needed time to be and to find those who would know how to see us as we are.

We needed time to find those who would see us, not from above or below, but face to face, who would see us with the gaze of a compañero.

So then, as I mentioned, the work of constructing this character began.

One day Marcos’ eyes were blue, another day they were green, or brown, or hazel, or black — all depending on who did the interview and took the picture. He was the back-up player of professional soccer teams, an employee in department stores, a chauffeur, philosopher, filmmaker, and the etcéteras that can be found in the paid media of those calendars and in various geographies. There was a Marcos for every occasion, that is to say, for every interview. And it wasn’t easy, believe me, there was no Wikipedia, and if someone came over from Spain we had to investigate if the Corte Inglés was a typical English-cut suit, a grocery store, or a department store.

If I had to define Marcos the character, I would say without a doubt that he was a colorful ruse.

We could say, so that you understand me, that Marcos was Non-Free Media (note: this is not the same as being paid media).

In constructing and maintaining this character, we made a few mistakes.

“To err is human,”[1] as they say.

During the first year we exhausted, as they say, the repertoire of all possible “Marcoses.” And so by the beginning of 1995, we were in a tight spot and the communities’ work was only in its initial steps.

And so in 1995 we didn’t know what to do. But that was when Zedillo, with the PAN at his side, “discovered” Marcos using the same scientific method used for finding remains, that is to say, by way of an esoteric snitching.

The story of the guy from Tampico gave us some breathing room, even though the subsequent fraud committed by Paca de Lozano made us worry that the paid press would also question the “unmasking” of Marcos and then discover that it was just another fraud. Fortunately, it didn’t happen like that. And like this one, the media continued swallowing similar pieces from the rumor mill.

Sometime later, that guy from Tampico showed up here in these lands. Together with Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés, we spoke to him. We offered to do a joint press conference so that he could free himself from persecution, since it would then be obvious that he and Marcos weren’t the same person. He didn’t want to. He came to live here. He left a few times and his face can be seen in the photographs of the funeral wakes of his parents. You can interview him if you want. Now he lives in a community, in…

[There is a pause here as the speaker leans over to ask Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés if it would be okay to mention where, to which the response is a firm “No.”]

Ah, he doesn’t want you to know exactly where this man lives. We won’t say any more so that if he wants to someday, he can tell the story of what he has lived since February 9, 1995. On our behalf, we just want to thank him for the information that he has given us which we use from time to time to feed the “certitude” that SupMarcos is not what he really is, that is to say, a ruse or a hologram, but rather a university professor from that now painful Tamaulipas.

In the meantime, we continued looking, looking for you, those of you who are here now and those who are not here but are with us.

We launched various initiatives in order to encounter the other, the other compañero, the other compañera. We tried different initiatives to encounter the gaze and the ear that we need and that we deserve.

In the meantime, our communities continued to move forward, as did the change or hand-off of responsibilities that has been much or little discussed, but which can be confirmed directly, without intermediaries.

In our search of that something else, we failed time and again.

Those who we encountered either wanted to lead us or wanted us to lead them.

There were those who got close to us out of an eagerness to use us, or to gaze backward, be it with anthropological or militant nostalgia.

And so for some we were communists, for others trotskyists, for others anarchists, for others millenarianists, and I’ll leave it there so you can add a few more “ists” from your own experience.

That was how it was until the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandón Jungle, the most daring and most Zapatista of all of the initiatives that we have launched up until now.

With the Sixth, we have at last encountered those who can see us face to face and greet us and embrace us, and this is how greetings and embraces are done.

With the Sixth, at last, we found you.

At last, someone who understood that we were not looking for shepherds to guide us, nor flocks to lead to the promised land. Neither masters nor slaves. Neither leaders nor leaderless masses.

But we still didn’t know if you would be able to see and hear what we are and what we are becoming.

Internally, the advance of our peoples has been impressive.

And so the course, “Freedom According to the Zapatistas” came about.

Over the three rounds of the course, we realized that there was already a generation that could look at us face to face, that could listen to us and talk to us without seeking a guide or a leader, without intending to be submissive or become followers.

Marcos, the character, was no longer necessary.

The new phase of the Zapatista struggle was ready.

So then what happened happened, and many of you, compañeros and compañeras of the Sixth, know this firsthand.

They may later say that this thing with the character [of Marcos] was pointless. But an honest look back at those days will show how many people turned to look at us, with pleasure or displeasure, because of the disguises of a colorful ruse.

So you see, the change or handoff of responsibilities is not because of illness or death, nor because of an internal dispute, ouster, or purging.

It comes about logically in accordance with the internal changes that the EZLN has had and is having.

I know this doesn’t square with the very square perspectives of those in the various “aboves,” but that really doesn’t worry us.

And if this ruins the rather poor and lazy explanations of the rumorologoists and zapatologists of Jovel [San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas], then oh well.

I am not nor have I been sick, and I am not nor have I been dead.

Or rather, despite the fact that I have been killed so many times, that I have died so many times, here I am again.

And if we ourselves encouraged these rumors, it was because it suited us to do so.

The last great trick of the hologram was to simulate terminal illness, including of the deaths supposedly suffered.

Indeed, the comment “if his health permits” made by Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés in the communiqué announcing the events with the CNI [National Indigenous Congress], was the equivalent of the “if the people ask for me,” or “if the polls favor me,” or “if it is god’s will,” and other clichés that have been the crutch of the political class in recent times.

If you will allow me one piece of advice: you should cultivate a bit of a sense of humor, not only for your own mental and physical health, but because without a sense of humor you’re not going to understand Zapatismo. And those who don’t understand, judge; and those who judge, condemn.

In reality, this has been the simplest part of the character. In order to feed the rumor mill it was only necessary to tell a few particular people: “I’m going to tell you a secret but promise me you won’t tell anyone.”

And of course they told.

The first involuntary collaborators in the rumor about sickness and death have been the “experts in zapatology” in arrogant Jovel and chaotic Mexico City who presume their closeness to and deep knowledge of Zapatismo. In addition to, of course, the police that earn their salaries as journalists, the journalists that earn their salaries as police, and the journalists who only earn salaries, bad ones, as journalists.

Thank you to all of them. Thank you for your discretion. You did exactly what we thought you would do. The only downside of all this is that I doubt anyone will ever tell any of you a secret again.

It is our conviction and our practice that in order to rebel and to struggle, neither leaders nor bosses nor messiahs nor saviors are necessary. To struggle, one only needs a sense of shame, a bit of dignity, and a lot of organization.

As for the rest, it either serves the collective or it doesn’t.

What this cult of the individual has provoked in the political experts and analysts “above” has been particularly comical. Yesterday they said that the future of the Mexican people depended on the alliance of two people. The day before yesterday they said that Peña Nieto had become independent of Salinas de Gortari, without realizing that, in this schema, if one criticized Peña Nieto, they were effectively putting themselves on Salinas de Gortari’s side, and if one criticized Salinas de Gortari, they were supporting Peña Nieto. Now they say that one has to take sides in the struggle going on “above” over control of telecommunications; in effect, either you’re with Slim or you’re with Azcárraga-Salinas. And even further above, you’re either with Obama or you’re with Putin.

Those who look toward and long to be “above” can continue to seek their leader; they can continue to think that now, for real, the electoral results will be honored; that now, for real, Slim will support the electoral left; that now, for real, the dragons and the battles will appear in Game of Thrones; that now, for real, Kirkman will be true to the original comic in the television series The Walking Dead; that now, for real, tools made in China aren’t going to break on their first use; that now, for real, soccer is going to be a sport and not a business.

And yes, perhaps in some of these cases they will be right. But one can’t forget that in all of these cases they are mere spectators, that is, passive consumers.

Those who loved and hated SupMarcos now know that they have loved and hated a hologram. Their love and hate have been useless, sterile, hollow, empty.

There will not be, then, museums or metal plaques where I was born and raised. There will not be someone who lives off of having been Subcomandante Marcos. No one will inherit his name or his job. There will not be all-paid trips abroad to give lectures. There will not be transport to or care in fancy hospitals. There will not be widows or heirs. There will not be funerals, honors, statues, museums, prizes, or anything else that the system does to promote the cult of the individual and devalue the collective.

This figure was created and now its creators, the Zapatistas, are destroying it.

If anyone understands this lesson from our compañeros and compañeras, they will have understood one of the foundations of Zapatismo.

So, in the last few years, what has happened has happened.

And we saw that now, the outfit, the character, the hologram, was no longer necessary.

Time and time again we planned this, and time and time again we waited for the right moment — the right calendar and geography to show what we really are to those who truly are.

And then Galeano arrived with his death to mark our calendar and geography: “here, in La Realidad; now; in the pain and rage.”

V. Pain and Rage. Signs and Screams.

When we got here to the caracol of La Realidad, without anyone telling us to, we began to speak in whispers.

Our pain spoke quietly, our rage in whispers.

It was as if we were trying to avoid scaring Galeano away with these unfamiliar sounds.

As if our voices and step called to him.

“Wait, compa,” our silence said.

“Don’t go,” our words murmured.

But there are other pains and other rages.

At this very minute, in other corners of Mexico and the world, a man, a woman, an other, a little girl, a little boy, an elderly man, an elderly woman, a memory, is beaten cruelly and with impunity, surrounded by the voracious crime that is the system, clubbed, cut, shot, finished off, dragged away among jeers, abandoned, their body then collected and mourned, their life buried.

Just a few names:

Alexis Benhumea, murdered in the State of Mexico.

Francisco Javier Cortés, murdered in the State of Mexico.

Juan Vázquez Guzmán, murdered in Chiapas.

Juan Carlos Gómez Silvano, murdered in Chiapas.

El compa Kuy, murdered in Mexico City.

Carlo Giuliani, murdered in Italy.

Alexis Grigoropoulos, murdered in Greece.

Wajih Wajdi al-Ramahi, murdered in a Refugee Camp in the West Bank city of Ramallah. At 14 years old, he was shot in the back from an Israeli observation post. There were no marches, protests, or anything else in the streets.

Matías Valentín Catrileo Quezada, mapuche murdered in Chile.

Teodulfo Torres Soriano, compa of the Sixth, disappeared in Mexico City.

Guadalupe Jerónimo and Urbano Macías, comuneros from Cherán, murdered in Michoacan.

Francisco de Asís Manuel, disappeared in Santa María Ostula.

Javier Martínes Robles, disappeared in Santa María Ostula.

Gerardo Vera Orcino, disappeared in Santa María Ostula.

Enrique Domínguez Macías, disappeared in Santa María Ostula.

Martín Santos Luna, disappeared in Santa María Ostula.

Pedro Leyva Domínguez, murdered in Santa María Ostula.

Diego Ramírez Domínguez, murdered in Santa María Ostula.

Trinidad de la Cruz Crisóstomo, murdered in Santa María Ostula.

Crisóforo Sánchez Reyes, murdered in Santa María Ostula.

Teódulo Santos Girón, disappeared in Santa María Ostula.

Longino Vicente Morales, disappeared in Guerrero.

Víctor Ayala Tapia, disappeared in Guerrero.

Jacinto López Díaz “El Jazi”, murdered in Puebla.

Bernardo Vázquez Sánchez, murdered in Oaxaca.

Jorge Alexis Herrera, murdered in Guerrero.

Gabriel Echeverría, murdered in Guerrero.

Edmundo Reyes Amaya, disappeared in Oaxaca.

Gabriel Alberto Cruz Sánchez, disappeared in Oaxaca.

Juan Francisco Sicilia Ortega, murdered in Morelos.

Ernesto Méndez Salinas, murdered in Morelos.

Alejandro Chao Barona, murdered in Morelos.

Sara Robledo, murdered in Morelos.

Juventina Villa Mojica, murdered in Guerrero.

Reynaldo Santana Villa, murdered in Guerrero.

Catarino Torres Pereda, murdered in Oaxaca.

Bety Cariño, murdered in Oaxaca.

Jyri Jaakkola, murdered in Oaxaca.

Sandra Luz Hernández, murdered in Sinaloa.

Marisela Escobedo Ortíz, murdered in Chihuahua.

Celedonio Monroy Prudencio, disappeared in Jalisco.

Nepomuceno Moreno Nuñez, murdered in Sonora.

The migrants, men and women, forcefully disappeared and probably murdered in every corner of Mexican territory.

The prisoners that they want to kill through “life”: Mumia Abu Jamal, Leonard Peltier, the Mapuche, Mario González, Juan Carlos Flores.

The continuous burial of voices that were lives, silenced by the sound of the earth thrown over them or the bars closing around them.

And the greatest mockery of all is that with every shovelful of dirt thrown by the thug currently on shift, the system is saying: “You don’t count, you are not worth anything, no one will cry for you, no one will be enraged by your death, no one will follow your step, no one will hold up your life.”

And with the last shovelful it gives its sentence: “even if they catch and punish those who killed you, we will always find another, an other, to ambush and on whom to repeat the macabre dance that ended your life.”

It says: “The small, stunted justice you will be given, manufactured by the paid media to simulate and obtain a bit of calm in order to stop the chaos coming at them, does not scare me, harm me, or punish me.”

What do we say to this cadaver who, in whatever corner of the world below, is buried in oblivion?

That only our pain and rage count?

That only our outrage means anything?

That as we murmur our history, we don’t hear their cry, their scream?

Injustice has so many names, and provokes so many screams.

But our pain and our rage do not keep us from hearing them.

And our murmurs are not only to lament the unjust fall of our own dead.

They allow us to hear other pains, to make other rages ours, and to continue in the long, complicated, tortuous path of making all of this into a battle cry that is transformed into a freedom struggle.

And to not forget that while someone murmurs, someone else screams.

And only the attentive ear can hear it.

While we are talking and listening right now, someone screams in pain, in rage.

And so it is as if one must learn to direct their gaze; what one hears must find a fertile path.

Because while someone rests, someone else continues the uphill climb.

In order to see this effort, it is enough to lower one’s gaze and lift one’s heart.

Can you?

Will you be able to?

Small justice looks so much like revenge. Small justice is what distributes impunity; as it punishes one, it absolves others.

What we want, what we fight for, does not end with finding Galeano’s murderers and seeing that they receive their punishment (make no mistake, this is what will happen).

The patient and obstinate search seeks truth, not the relief of resignation.

True justice has to do with the buried compañero Galeano.

Because we ask ourselves not what do we do with his death, but what do we do with his life.

Forgive me if I enter into the swampy terrain of commonplace sayings, but this compañero did not deserve to die, not like this.

His tenacity, his daily punctual sacrifice, invisible for anyone other than us, was for life.

And I can assure you that he was an extraordinary being and that, what’s more — and this is what amazes — there are thousands of compañeros and compañeras like him in the indigenous Zapatista communities, with the same determination, the same commitment, the same clarity, and one single destination: freedom.

And, doing macabre calculations: if someone deserves death, it is he who does not exist and has never existed, except in the fleeting interest of the paid media.

As our compañero, chief and spokesperson of the EZLN, Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés has already told us, in killing Galeano, or any Zapatista, those above are trying to kill the EZLN.

Not the EZLN as an army, but as the rebellious and stubborn force that builds and raises life where those above desire the wasteland brought by the mining, oil, and tourist industries, the death of the earth and those who work and inhabit it.

He has also said that we have come, as the General Command of the Zaptaista Army for National Liberation, to exhume Galeano.

We think that it is necessary for one of us to die so that Galeano lives.

To satisfy the impertinence that is death, in place of Galeano we put another name, so that Galeano lives and death takes not a life but just a name — a few letters empty of any meaning, without their own history or life.

That is why we have decided that Marcos today will cease to exist.

He will go hand-in-hand with Shadow the Warrior and the Little Light so that he doesn’t get lost on the way. Don Durito will go with him, Old Antonio also.

The little girls and boys who used to crowd around to hear his stories will not miss him; they are grown up now, they have their own capacity for discernment; they now struggle like him for freedom, democracy, and justice, which is the task of every Zapatista.

It is the cat-dog, and not a swan, who will sing his farewell song.

And in the end, those who have understood will know that he who never was here does not leave; that he who never lived does not die.

And death will go away, fooled by an indigenous man whose nom de guerre was Galeano, and those rocks that have been placed on his tomb will once again walk and teach whoever will listen the most basic tenet of Zapatismo: that is, don’t sell out, don’t give in, don’t give up.

Oh death! As if it wasn’t obvious that it frees those above of any responsibility beyond the funeral prayer, the bland homage, the sterile statue, the controlling museum.

And for us? Well, for us death commits us to the life it contains.

So here we are, mocking death in reality [La Realidad].

Compas:

Given the above, at 2:08am on May 25, 2014, from the southeast combat front of the EZLN, I here declare that he who is known as Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, self-proclaimed “Subcomandante of Stainless Steel,” ceases to exist.

That is how it is.

Through my voice the Zapatista Army for National Liberation no longer speaks.

Vale. Health and until never or until forever; those who have understood will know that this doesn’t matter anymore, that it never has.

From the Zapatista reality,

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos. Mexico, May 24, 2014.

P.S. 1. Game over?

P.S. 2. Check mate?

P.S. 3. Touché?

P.S. 4. Go make sense of it, raza, and send tobacco.

P.S. 5. Hmm… so this is hell… It’s Piporro, Pedro, José Alfredo! What? For being machista? Nah, I don’t think so, since I’ve never…

P.S. 6. Great, now that the mask has come off, I can walk around here naked, right?

P.S.7. Hey, it’s really dark here, I need a little light.

(…)

[He lights his pipe and exits stage left. Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés announces that “another compañero is going to say a few words.”]

(a voice is heard offstage)

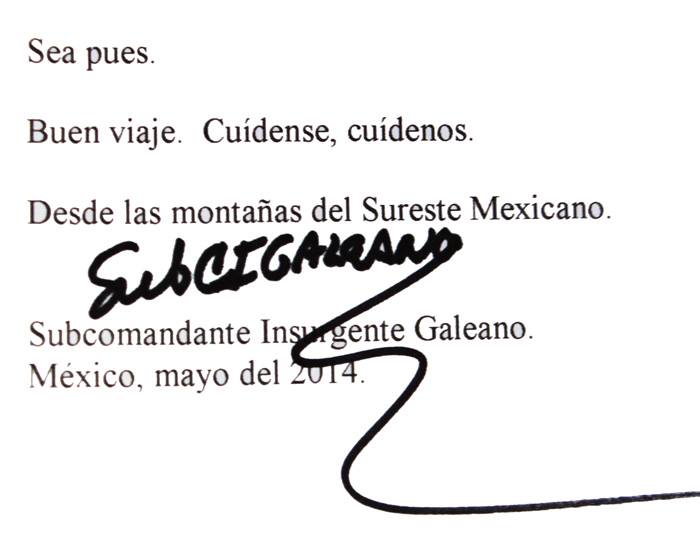

Good morning compañeras and compañeros. My name is Galeano, Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano.

Anyone else here named Galeano?

[the crowd cries, “We are all Galeano!”]

Ah, that’s why they told me that when I was reborn, it would be as a collective.

And so it should be.

Have a good journey. Take care of yourselves, take care of us.

From the mountains of the Mexican Southeast,

Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano

Mexico, May of 2014.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/essays/subcomandante-galeano-between-light-shadow/