gig economy

Gig workers were deemed to be “unorganizable” — but Deliveroo riders in the UK have shown that workers still have the power to change the world.

Delivery Drivers Take On the Platform Goliaths

- Issue #

- Authors

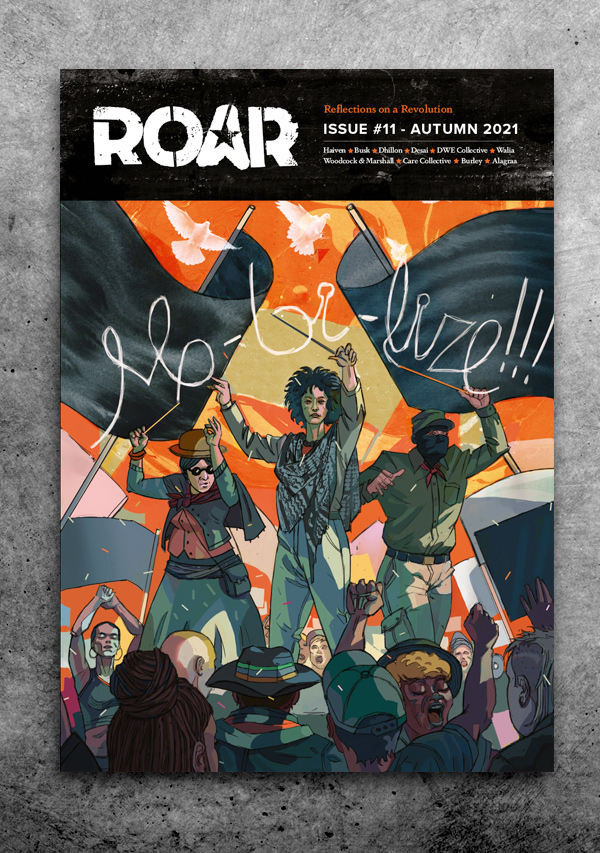

On April 7, 2021, Deliveroo riders met on the streets of London: flags and banners were unfurled, megaphones were raised and chants started. The riders set off towards the platform giant’s London headquarters, blocking traffic on the way. Outside of the headquarters the protest grew, with music and red flares adding to the strike action. Deliveroo riders were demanding improvements in their conditions and pay and speaking out against sudden “deactivations,” where drivers are fired without any remit for appeal.

As Joseph Durbridge, a London-based Deliveroo rider, explained:

I cannot rely on Deliveroo for a hundred percent of my income. I’ve worked throughout the pandemic and it’s difficult to make ends meet. Deliveroo’s hiring more people and endlessly driving our income down. It doesn’t care about the financial security or basic rights of its riders and shamelessly claims the workforce is largely casual.

These workers have become a symbol of the gig economy in the UK, characterized by unstable, fleeting jobs on a freelance or short-term contract basis — a far cry from the job-for-life predictability of traditional waged employment. The gig economy has grown rapidly over the last ten years in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, with many types of work becoming more precarious. As secure employment becomes more of a rarity, there is a massive increase in novel forms of self-employment throughout the economy. At the center of all this is the dramatic rise of platform companies that use digital tools to connect workers with customers, for example connecting delivery drivers to customers and restaurants. Transportation has been a focus of these new platforms, with companies like DoorDash and GrubHub alongside Deliveroo in food delivery, or Uber and Lyft in private hire transportation.

When Deliveroo first started in London in 2013, many commentators noted the major barriers these workers faced in terms of organizing — with the more pessimistic claiming that they were “unorganizable.” Proving them wrong, the Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain (IWGB) has been organizing with Deliveroo riders and other gig workers since 2016, clocking up a number of real victories in the process.

The IWGB’s fight in support of platform workers can provide lessons for how our movements can take on the challenges that face us over the next ten years. As the union notes, “We’re just one David and there’s a lot of Goliaths out there.” In preparation for the battles to come, the union’s history of campaigning with delivery drivers, bicycle couriers, outsourced cleaners and other precarious workers has provided an important training ground to test the kind of creative tactics necessary to take on the new Goliaths of multinational companies in the coming years.

The rise of organizing in the gig economy

Over the past decade we have seen a growth of worker organizing in the gig economy, with strikes and protests becoming more common. Nearly a decade ago, Latin American migrant cleaners working at universities in London began to organize themselves. They were marginalized in both their workplaces and the mainstream union movement but nonetheless managed to form and build a new kind of union, the IWGB. Since then, the union has grown to organize with precarious and migrant workers across different sectors, including cleaners in other sectors, couriers, private hire drivers, foster care workers, nannies, game workers and others. Against the trend of long-term decline in trade unionism in the UK, the IWGB has been growing year-on-year.

Deliveroo is but one voice in the chorus claiming that work has fundamentally changed in the “on-demand economy.” The traditional roles of bosses and workers have been replaced by a shiny technological interface that connects people that offer their labor to those who want a service. This is an attempt at hiding the employment relationship behind Silicon Valley tech-optimism, advertising and extensive political lobbying.

The promise of flexibility through self-employment has turned into precarious work for many.

In keeping with the free-market mantra, platforms like Deliveroo and Uber have consistently tried to wriggle free of those limiting employment protections and responsibilities that the labor movement has fought for over generations. Without employment status there is no legal right to minimum wage, sick or holiday pay, pensions or trade union representation. Engaging workers as self-employed removes employment rights, but it also keeps the workers off the company books, making it look even more attractive to venture capital as it avoids costs and liabilities. If Uber were to employ its drivers, it would be the largest private employer in the world — even bigger than Amazon.

As the IWGB has argued many times, this is “bogus self-employment.” In the words of Jason Moyer Lee, the previous General Secretary of the IWGB: “There is nothing, either logically or legally, to suggest that workers can’t work flexibly.” In other words, having a flexible working pattern should not force anyone to give up employment or worker status. The promise of flexibility through self-employment — the freedom to determine one’s own working hours — has turned into precarious work for many, with workers expected to be on call 24/7 and the impact this has on their physical and mental well-being.

Outsourcing and the gig economy

This process, however new it may seem in many ways, is not without a history. In the UK, it began in the late 1970s with the election of Margaret Thatcher as prime minister, marking the start of the era of neoliberal capitalism. Attacks on working conditions are one part of this, so is the rollback of the welfare state, the advance of the security state, deregulation and the opening up of public services and increasing parts of our lives to privatization and “the market.” Outsourcing is an important part of this deregulation, following the myth that a liberalization of the market and privatization will lead to greater efficiency and lower costs. The reality for workers is that another intermediary profits from their work, while the safety net and protections they previously had are pulled away.

When the IWGB was formed in 2012, the migrant workers who cleaned Senate House at the University of London were employed by an agency rather than the university itself. Previously, all workers were directly employed by the university. This change to using an external company is not the same as forcing workers into self-employment contracts like in the gig economy, but it works on very similar principles. For university management, outsourcing allowed them to drive down workers’ pay and conditions, while refuting all responsibility for their management.

Outsourcing is widespread in the UK. For example, in 2018 the UK government spent £284 billion — a third of all public expenditure — buying goods and services from external suppliers. While not all of this is outsourced work, across many public sector institutions from the NHS to schools, outsourcing has become commonplace.

The reality for workers is that another intermediary profits from their work, while the safety net and protections they previously had are pulled away.

The type of outsourcing the cleaners were subjected to is contractual: workers still come into the same building but are now employed by a separate company. For universities, it means they can claim not to know how little workers are being paid to clean lecture halls and buildings. The university no longer treats outsourced workers like other people they employ, isolating them from the rest of the workforce. This means that when cleaners go on strike — which they have many times in the last decade — they are targeting a different employer to academics and admin staff, despite both working in the same place.

Over the last ten years, the IWGB has fought a campaign at Senate House for workers to be brought back in house — ending the outsourcing contracts and improving pay and conditions. This was a fight led by Latin American migrant workers who took on a prestigious university in one of the capitals of global capitalism. The workers outlasted three different outsourcing companies, being reemployed by OCS, Balfour Beatty and then lastly Cordant, before being brought back in house. Their campaign took lessons from the Justice for Janitors campaign in the 1990s in the US, starting by searching for new ways to get leverage over employers. This included many years of organizing in the community and engaging in civil disobedience, mass protests, strikes, boycotts and campaigns “principally aimed to make this invisible (and largely migrant) workforce highly visible in the public sphere.”

What outsourced cleaning work and platform gig work have in common is that they are both subjected to contractual tricks to push the responsibilities and requirements away from the employer and onto someone else. With outsourcing, this pushes the responsibility onto another company, while in gig work it is pushed onto the workers themselves. In a sense, gig work is a new and even more extreme form of outsourcing. They are both part of a play by companies to attack worker rights and reconfigure the economy in the interests of employers — all in accordance with the neoliberal playbook and its discourse of market freedom and choice.

Decline of the trade union movement

From the 1980s, the trade union movement has been in decline in the UK. Membership almost halved between the 1970s and the 2000s. While some of this can be explained by the shrinking of traditional industries of docking, printing, steel and coal, the environment in which trade unions operate has also become increasingly hostile. Legislation has restricted union power, banning forms of action like secondary picketing and forcing strike votes to be held by lengthy postal ballots. The new service industries have not been unionized and many workers in the private sector simply are not reached by trade unions.

The successful struggle of the University of London cleaners, who, despite the many challenges they faced — including migration status, xenophobia and language barriers — were leading struggles here in the UK, was an inspiration to other groups of precarious workers. In 2015, bicycle couriers joined the IWGB, forming a new branch to try and do something similar in their industry. The courier industry has a long history in London, moving documents and other items across the city. In a congested city like London, bicycles have a major advantage in being able to do this quickly. There was already a history of couriers supporting each other too: a self-organized “London Courier Emergency Fund” was established in 2008 to support those off work from an injury.

The trade union organizing focused on getting pay rises at courier companies and then challenging the self-employment status. There were high profile victories that combined worker organizing with legal cases at CitySprint, eCourier and others across London.

The campaign at Deliveroo

This is the wider context within which the first strike of platform workers took place. In August 2016, the WhatsApp groups of Deliveroo workers across London came alive with calls for a strike. Without a union or any formal organization, workers organized a strike in opposition to Deliveroo plans for a new lower payment scheme. In the run-up to the strike, a few workers got in touch with the IWGB, having seen the successes of earlier campaigns by couriers and cleaners. On the first day of the strike, organizers from the IWGB were there to support the action.

The strike was widely covered in the media and attracted widespread support — both in the UK and internationally. At the time, the changes were briefly pushed back, but the new payment model was eventually rolled out across the UK. Workers were not able to win concessions from Deliveroo, who refused to enter negotiations. But after the strike, some of the workers were recruited into the union, organizing with the Couriers and Logistics branch of the IWGB. Over the past five years, the IWGB has developed structures for these workers, but Deliveroo has so far refused to either recognize or negotiate with the union.

After the 2016 strike in London, Deliveroo workers took action in other cities in the UK and across Europe. This included actions in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands. As Callum Cant has argued, there were two waves of struggle that spread across the platform, with increased coordination between countries. Workers formed the Transnational Couriers Federation, sharing tactics and solidarity with strikes across the borders of Europe. From 2016, the strike became a popular form of action, spreading not only across Europe and Deliveroo, but happening globally across different platforms in North America, South America and Asia. These have primarily been about issues of pay, but also about the lack of communication, firing and deactivations without appeal and general working conditions. Deliveroo has now become the platform with the most worker protests and strikes globally, accounting for over a quarter of all labor actions in the food delivery sector between 2017 and 2020.

Deliveroo has now become the platform with the most worker protests and strikes globally, accounting for over a quarter of all labor actions in the food delivery sector between 2017 and 2020.

The IWGB continues to experiment with different ways to organize at Deliveroo. The union launched the Riders Roovolt campaign to focus specifically on organizing at the company. This has involved doing casework — trying to solve specific grievances that workers are having about discrimination, termination and unfounded accusations, among others things — taking Deliveroo to court over employment status and continuing to organize and support strikes and protests. Across the five years, wildcat strikes have continued to break out in different neighborhoods or targeted at specific restaurants. While there can be tension between restaurant workers and delivery workers — particularly in relation to waiting times — there has also been solidarity and even a widely covered shared strike day between workers at UberEats and McDonalds. More recently, there have been some successes with casework and the development of union structures among Deliveroo workers.

In the context of low trade union membership, the IWGB has almost had to reintroduce the very idea of being in a union to many people. The labor movement has been on the defensive for many years — attacked by both the government and the media — which means pro-union attitudes are not always common. Many young workers may never have encountered a union at work before. Migrant workers can bring experiences of militancy from other countries, refreshing the labor movement with new and creative ideas. This has been the case in many other branches of the IWGB but many couriers explain that they have had negative experiences in unions before — either not feeling represented by them or failing to get support. The pitch of the IWGB as a “new” union, not one that accommodates employers, can therefore be an advantage.

Newer unions can have an agility that is rarer in the older and more traditional unions. At the same time, they also have fewer resources and less capacity. All in all, however, the newer unions tend to have an environment where it is easier to change how organizing is done and to experiment with new methods — which is vitally important for organizing with Deliveroo workers. This requires adapting to workers’ circumstances and ensuring members can participate across the city. It can be unpredictable and the turnover means that organization can fall away. Street stalls, WhatsApp groups, Zoom calls, spaces to meet, interpreters and translations are all needed to do this work effectively. For these workers, this is an immense struggle under extremely strenuous conditions; trying to build up a fight against a platform Goliath that operates internationally, often outside of employment law and which has vast capital backing it up.

Building gig worker power

There have been two ways that this unequal power relationship has been addressed in practice. The first has involved workers choosing targets other than the Goliath itself. Rather than taking on the bigger Deliveroo, there have been confrontations with specific restaurants that are known to be difficult to pick up from either because of long waiting times, lack of space or abusive managers. Campaigns have targeted restaurants like Wagamama and McDonalds to force smaller concessions, which has helped build the workers’ confidence and combativity.

Campaigns targeting specific restaurants provide small wins, and they also allow for the targeting of supposedly ethical restaurants who want to present as being fair to workers and so can be particularly susceptible to public campaigns. In trying to understand the work dynamics and its hierarchies, it is important to note that managers who mistreat delivery workers are likely behaving in a similar way towards workers in the restaurant, presenting the possibility for solidarity along the supply chain, as happened with the McDonalds and UberEats strike. Similarly, local councils can become another point of confrontation — when they try to ban workers from meeting or when they issue parking tickets. In these cases, David’s slingshot is being pointed at other targets, but this is more than simple target practice.

There is no such thing as “unorganizable” workers — just yet-to-be organized.

The second approach involves finding ways to leverage more into the slingshot aimed directly at Deliveroo. On April 7, 2021, Deliveroo launched their IPO (Initial Public Offering — when shares are sold to investors) in London. This was a moment when Deliveroo became particularly vulnerable to public pressure. The IWGB’s strike action discussed above took place on this very day, with protests outside the platform’s London headquarters.

In the run-up to this event, the union organized a campaign that drew on a serious range of tactics. The union has been key to building up an international network that includes support from unions across the world: TWU in Australia, CGT in France, FNV in the Netherlands, SIPTU in Ireland and UGT in Spain. In addition, the campaign managed to gather support from over 70 Members of Parliament in the UK. Lastly, a collaboration between the IWGB and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism showed that some drivers earn as little as £2 per hour. This part of the campaign focused on targeting investors and successfully led to 12 major investment firms withdrawing from the IPO, citing concerns over workers’ rights as the reason. The result was an IPO that the Financial Times described as “the worst IPO in London’s history,” with almost £2 billion wiped from Deliveroo’s opening £7.6 billion market capitalization.

Deliveroo continues to refuse to recognize or negotiate with the IWGB. Once the furore over the IPO had settled, the platform made a series of changes to working conditions in response to the pressure they had come under. There is now some semblance of sick-pay provided by the platform, though it only covers workers that have maintained regular work, they are required to have been off work for at least eight days and it can only be claimed twice per year. A one-off payment of £1,000 for maternity and paternity pay is now available to workers too.

The inclusion of these rights is part of the fight the IWGB has waged against Deliveroo from the start. Unsurprisingly, they have not mentioned that these changes have come about through workers’ own initiatives, but it is a sign that the gig economy is beginning to change. New entrants into the UK market, like Getir and Gorillas, are employing workers with contracts, rather than using the bogus self-employment model that Deliveroo has relied upon.

Learning from these struggles

The story of the IWGB is one of workers that were written off as “unorganizable.” It is a story of a new part of the labor movement being forged through struggles against employers, outsourcing companies and platforms. The IWGB has learned many lessons over the past ten years. The first is that there is no such thing as “unorganizable” workers — just yet-to-be organized. There is an expanding range of tactics that can be put to use in these struggles, involving strikes and action at work, as well as building leverage outside the workplace.

The most important lesson is that all struggles are worth fighting. The IWGB story is one of getting commitment from workers to fight, something that is particularly difficult in short-term gig work. There is an incredibly high turnover at Deliveroo, with the average worker staying for only ten months. The fight has therefore required overcoming the structural challenges of precarious work, turning the tide of decline in the trade union movement in the process.

Struggles like these are not won in a single cinematic moment where the power balance is upturned and Goliath is righteously struck down. Instead, these fights are won by bombarding the target from many angles without giving up. It takes long-term organizing that builds workers’ self-activity and confidence. In practice, this means starting from the power that workers have at work — whether as cleaners in a university or delivering food across the city — that it is their labor that the employer relies upon.

Read the full issue here.

Withdrawing this labor — or the threat of doing so — is still the most powerful tool that workers have. This can be used to fight for better conditions in the workplace or in solidarity with others. Action can build alliances between different groups of workers, whether across the different IWGB branches or more widely. However, the struggles of the past ten years show that it is obviously not the only tool: strikes can be combined with other forms of action too.

In the next ten years, the workers movement will be facing many challenges. This will not only be new attacks on workers or the increase of precarious employment in the gig economy, but the wider struggle for control over our lives and the future of human life on this planet. As the apocalyptic effects of climate change are being felt, we face a global fight that we cannot afford to lose.

The struggles of the IWGB have shown the importance of solidarity and commitment to campaigns that will be needed in the future. The lesson to take from organizing in the gig economy is that workers still have the power to change the world. It is with this belief that we should load our slingshots for the struggles against the new Goliaths — from the workplace to the future of our planet. Not only to reverse the catastrophic effects of climate change, but to build a better future for us all.

Source URL — https://roarmag.org/magazine/gig-worker-organizing/

Next Magazine article

Building Anti-Colonial Feminist Coalitions Against Climate Change

- Jaskiran Dhillon

- December 15, 2021

De-gendering Care: The Key to Address the Care Crisis

- The Care Collective

- December 15, 2021